Gokui Training: Japan Report Two 令和6年

From Bujinkan Santa Monica by Michael

I began this day by catching a train to the Bujinkan Honbu Dojo for a class with Furuta Sensei. In the past few years I’ve been able to train with him quite a bit. And each class gives me a little more insight into the gokui of 雲隠流 Kumogakure Ryū and Ninjutsu.

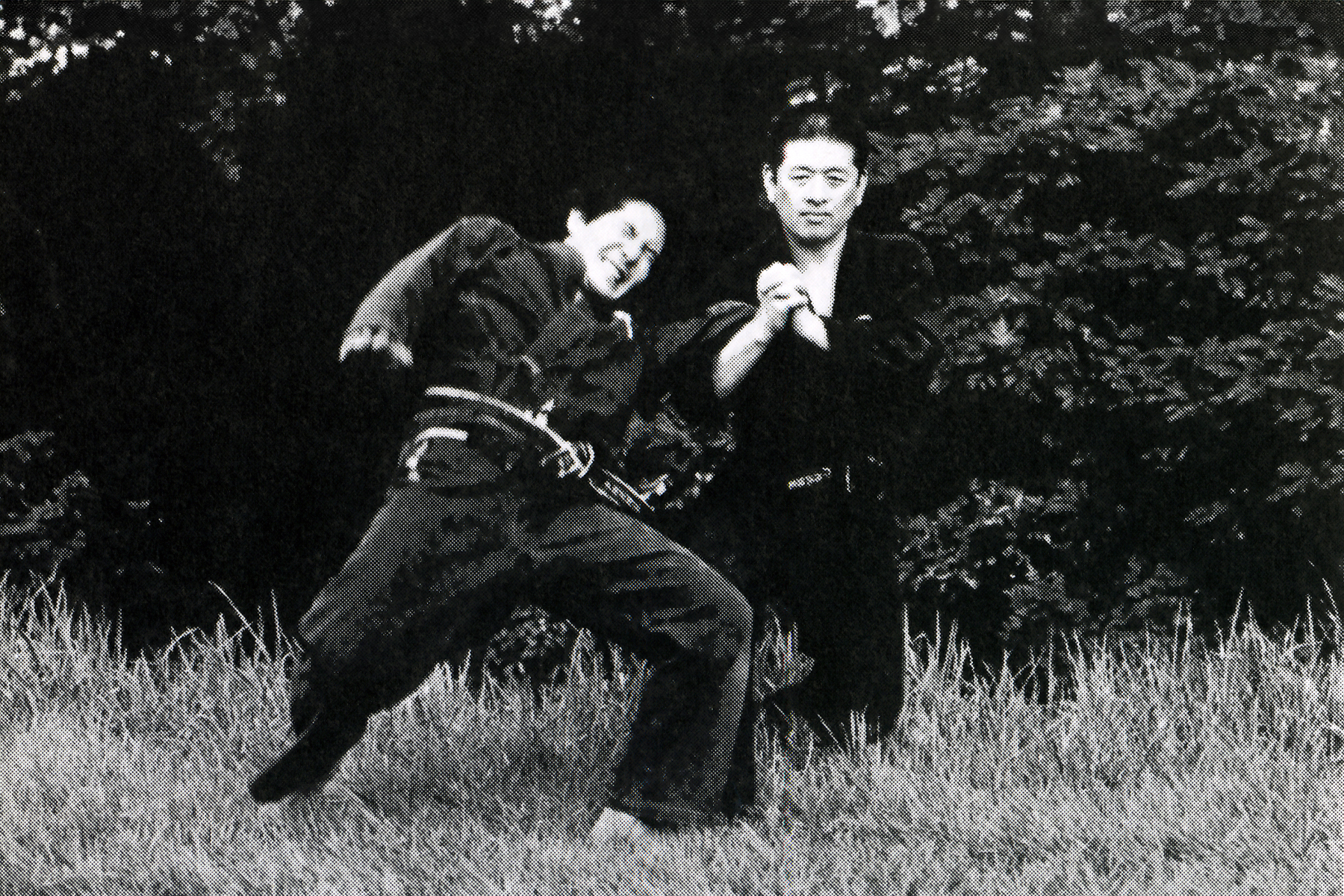

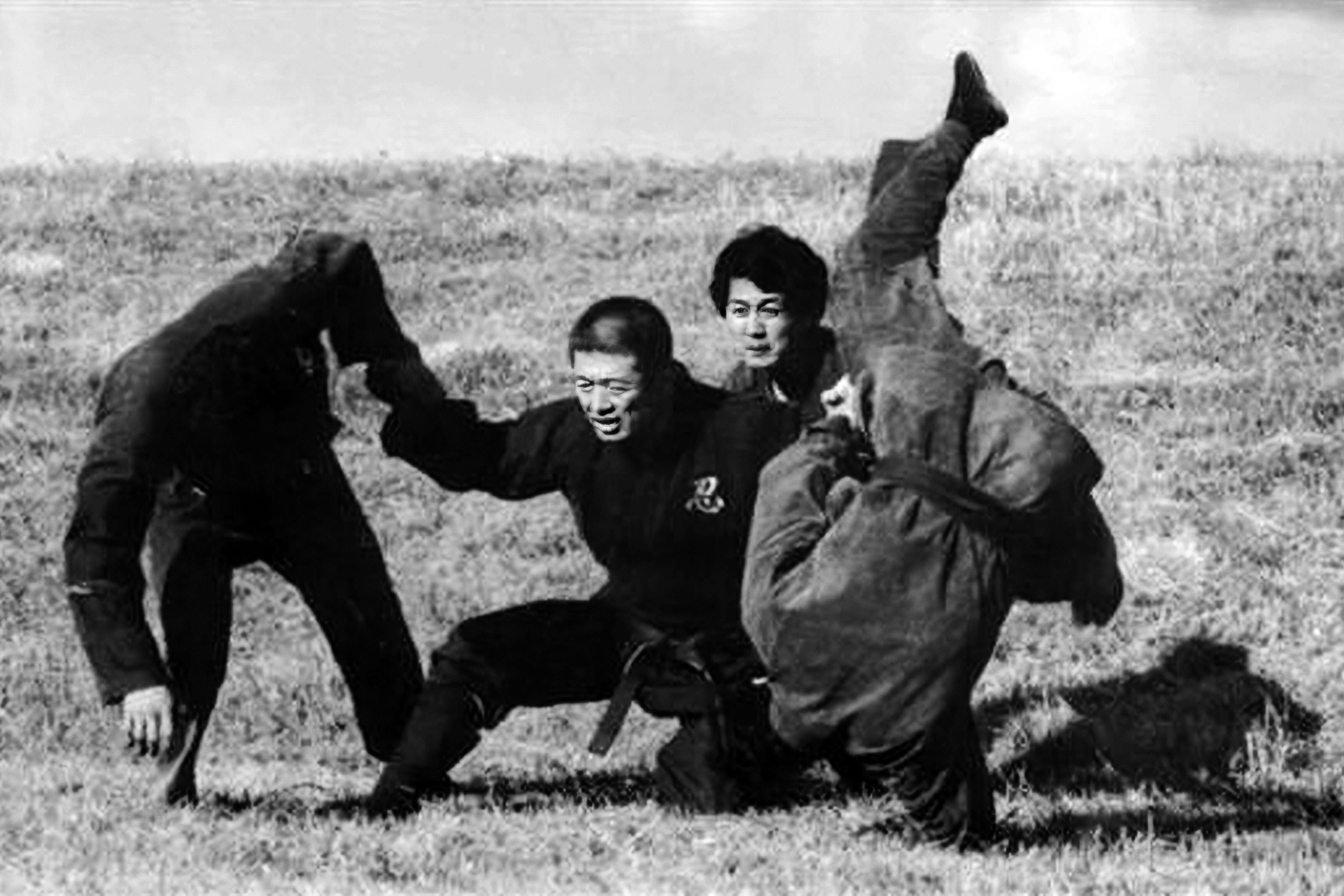

Furuta Sensei began class using 乱勝 Ranshō as a springboard to explore many ideas. He would use a dramatic drop or lean in his body to evade and upset his opponent’s balance. He also shifts this way to hide within the opponent’s movement.

When he called me to be his uke, he blocked my attack, but the way he held his other hand gave me the impression that I could attack again. Then Furuta Sensei encouraged me to hit him. I said, “are you sure?” But this was intentional because he was baiting me. So when I went for it, I fell into the space as he hit me with an unseen strike.

He used this same feeling to access hidden weapons. If you’ve trained with Furuta, you know he always has a couple of knives on him. One moment I thought I had gotten away from him, then I felt a knife hit me in the foot. He had thrown it from a distance during my ukemi.

He had us do some mutō dori techniques, but he surprised us because as we did the evasion, Furuta Sensei attacked us with another sword from behind! Then he shared some gokui for dealing with multiple opponents and this live type of Godan test.

極意 Gokui Training

I went to 長全寺 Chōzenji to reflect on where I am at with my current training approach. I am not focused on basic fighting or combat, but rather on the level of gokui. This is how I expand my training to match the feeling I get from Hatsumi Sensei.

One might ask, 霊魂よ、そこにいますか。Because when a student is defeated in the dojo, or even worse, in combat, that moment is overwhelming. And they start to wonder what went wrong or why they failed. When the spirit is full of these doubts, it is very difficult to find the essence or the gokui.

What is the essence of defeat? A big lesson is to get back up and move forward. Perseverance is the gokui of life.

It is difficult to communicate to someone who is focused on technique, fighting, or winning the nature of this type of training. But if someone trains with me in person, they might feel it. Or maybe they can learn from some Japanese Shihan who are teaching this way.

Even though I am a still tired from training and travel, I went to Noguchi Sensei’s evening class. I drank some tea for a boost because his classes are energetic. He usually jams through a bunch of kata and henka.

When he first arrived at the Honbu dojo, someone asked him about his busy schedule last year with many taikai around the world. He commented that even though he enjoyed it, he was getting old and he would probably retire next year. I hope this was just a daydream on his part.

My friend László gave Noguchi Sensei a photo calendar with pictures from his mountaineering expeditions. Noguchi Sensei really admired these photos of snow covered peaks. I said to him, “when you retire you can take up mountain climbing.” He laughed and said he would rather stay home and drink beer.

Noguchi Sensei taught from the 初伝型 Shoden Gata level of 虎倒流骨法術 Kotō Ryū Koppōjutsu. He surprised me because he only made it through maybe half of them. But that didn’t mean the class was slow.

He emphasized taking a cross step during the strikes and evasions. Then he changed levels from 上段 Jōdan to 中段 Chūdan, and then 下段 Gedan. He also showed ura and omote with each kata.

Noguchi Sensei did grappling techniques against punching attacks, or the reverse. These are some of the ways he finds henka. But I think he makes this teaching choice to expose the gokui found in each kata. I’ve trained with him for many years so I can see some of his strategy for teaching and exploring taijutsu.

In one of the techniques he did on me, he took a unique angle in his evasion that caused my second punch to catch air. In that moment when I was off balance, I felt him attack my upper thigh. And that sent me sprawling.

My training partner said he didn’t see that strike. But I felt it hidden within the movement. It was as if the angle of evasion was a type of strike! I spent the rest of the class trying to understand that angle.

As I sit here writing my notes, I look forward to some sleep. But I am excited to see what tomorrow brings here in Japan. You can watch the video about my experience in Japan Report Three 令和6年 coming soon.

…