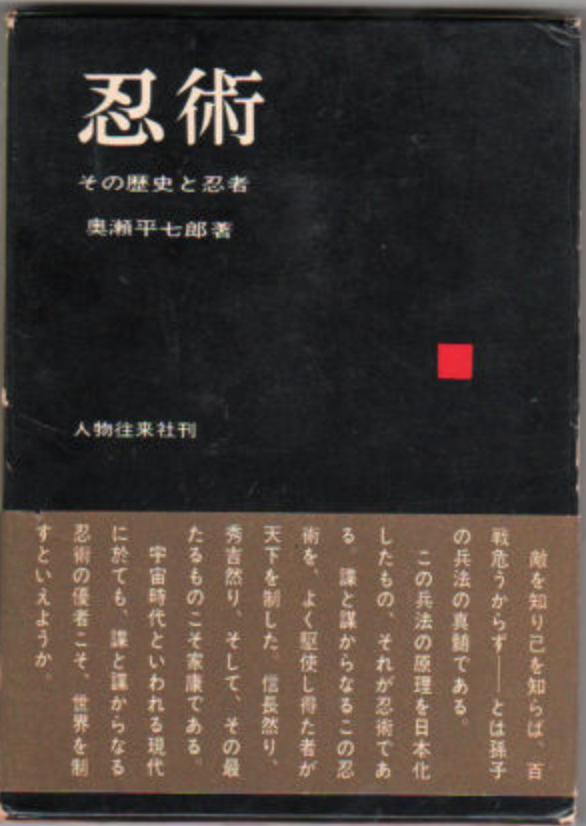

Be Incomplete!

From Shiro Kuma by kumablog

A class with Nagato sensei is never easy, even after training with him for 35 years. I know his taijutsu, I understand his movements, but I cannot get his flow.

That is what many practitioners often fail to understand. The Japanese Sōke and Dai Shihan will not teach you techniques; they will convey the essence of Bujinkan Budō. If you want to collect Waza, don’t come here.

You should do your homework in your dōjō before coming and be prepared. As I often write, I invite you to learn your basics and study the Tenchijin intensively. When all the fundamentals are acquired, it is easier to adjust your knowledge base to what the teachers demonstrate here. If you don’t do that, then basics and advanced movements are the same for you, and you miss the objectives of the classes. The teachers here are demonstrating advanced Budō. There is no basic training at Honbu!

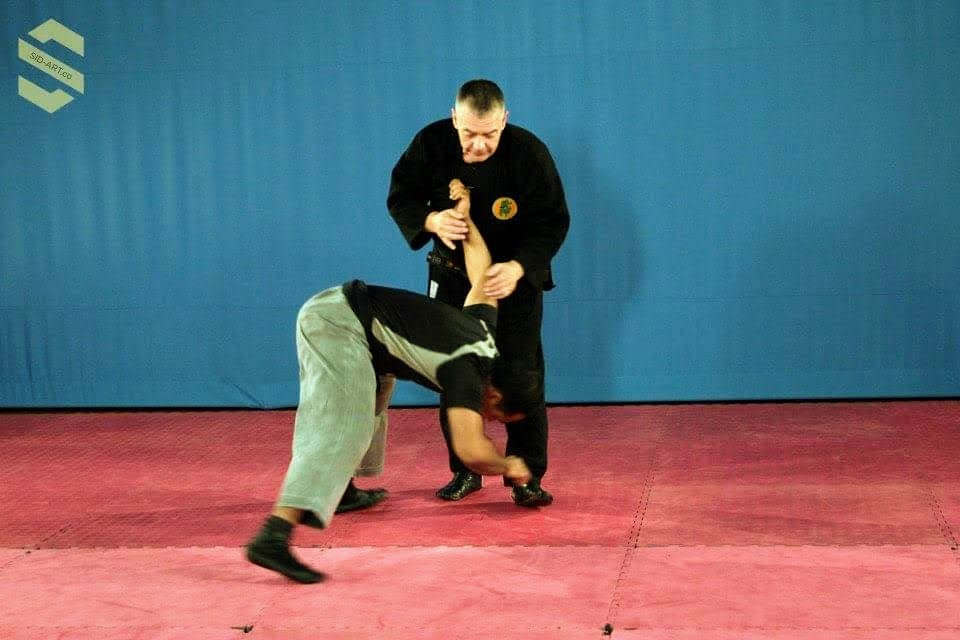

Nagato sensei asked a student to perform a movement. Then, they used it to demonstrate his usual style of Budō, which includes many subtle elbow movements. Playing a lot with distance, he always found a way to wrap up and control him with his elbows.

He spoke a lot about doing “half-cooked techniques”, a concept we studied a few years ago with Hatsumi Sensei. The idea is never to finish a waza but to use the opponent’s body reactions to initiate a new, natural movement. (1) That way, uke cannot read our intention as our moves originate from his reactions. That isn’t an easy task. You never finish a technique because uke’s moves trigger your actions.

After class, speaking with a few friends, we concluded that it was similar to when Sensei taught us the concept of the skipping stone, as seen in Ishitobashi. (2) We use the air pockets created and the uke’s reactions to move. Each point of contact with the uke is like a stone hitting the water. It is the start of a new movement.

Another detail Nagato sensei insisted on was not holding firmly at all times. When holding the wrist of the attacker, you grab him with very little strength and control him by letting your “C-shaped” grip slide around his wrist. (3) Because of the soft grip, there is no strong reaction on the uke’s part. That is very common, but we often tend to put force when it is not necessary.

During the break, Nagato sensei reminded us that “there’s nothing secret in Budō”, quoting Hatsumi sensei. Our egos would love to learn secrets, but there are none. The secret, if there is one, is to train your taijutsu well enough through the basics to extract as much as possible when here. We continue to learn in every class; tonight’s lesson was to “be incomplete” to create more opportunities. When you come here, you have to be half empty if you want to fill your head with new understandings. During the break, my friend Luis Bermejo from the Dominican Republic asked a question about the length of the path of Budō. And Nagato sensei answered, “The path never ends”.

PS: On the humorous side, Shiva was there with Nandi, and a Koi member, asked for a picture with me. While taking the pose, he saw Shiva. He said, “I think I saw him on Koimartialart”, not knowing that we created it together in India! (4)

PS 2: Don’t forget to register for the Paris Nagato Taikai at the end of the year. That is an opportunity to train with a great teacher. https://facebook.com/events/s/nagato-taikai-paris/1682157225737627/

____________________

- 中途/chūto/in the middle; half-way; 半端/hanpa/remnant; fragment; incomplete set; fraction; odd sum; incompleteness

- Ishitobashi 石飛ばし; skipping stones. Each contact with water creates an air pocket (the arch between the water and the flying stone), in which our Budō manifests. That is not visible to uke and, therefore, is impossible to counter.

- “C-shaped” grip: This is when you hold the wrist between your thumb and your forefinger. It is à common way to hold in many military self-defence courses.

- www.koimartialart.com: Online streaming platform in English with 160 Gb of videos.

…