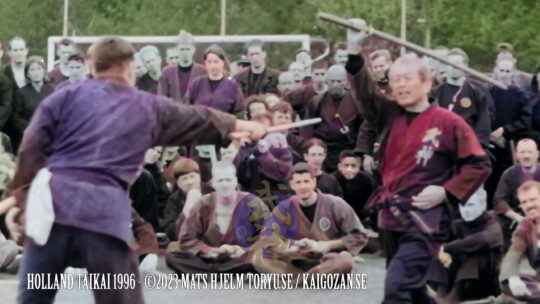

The Holland Taikai 1996: A Historic Bujinkan Seminar

From 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu by Toryu

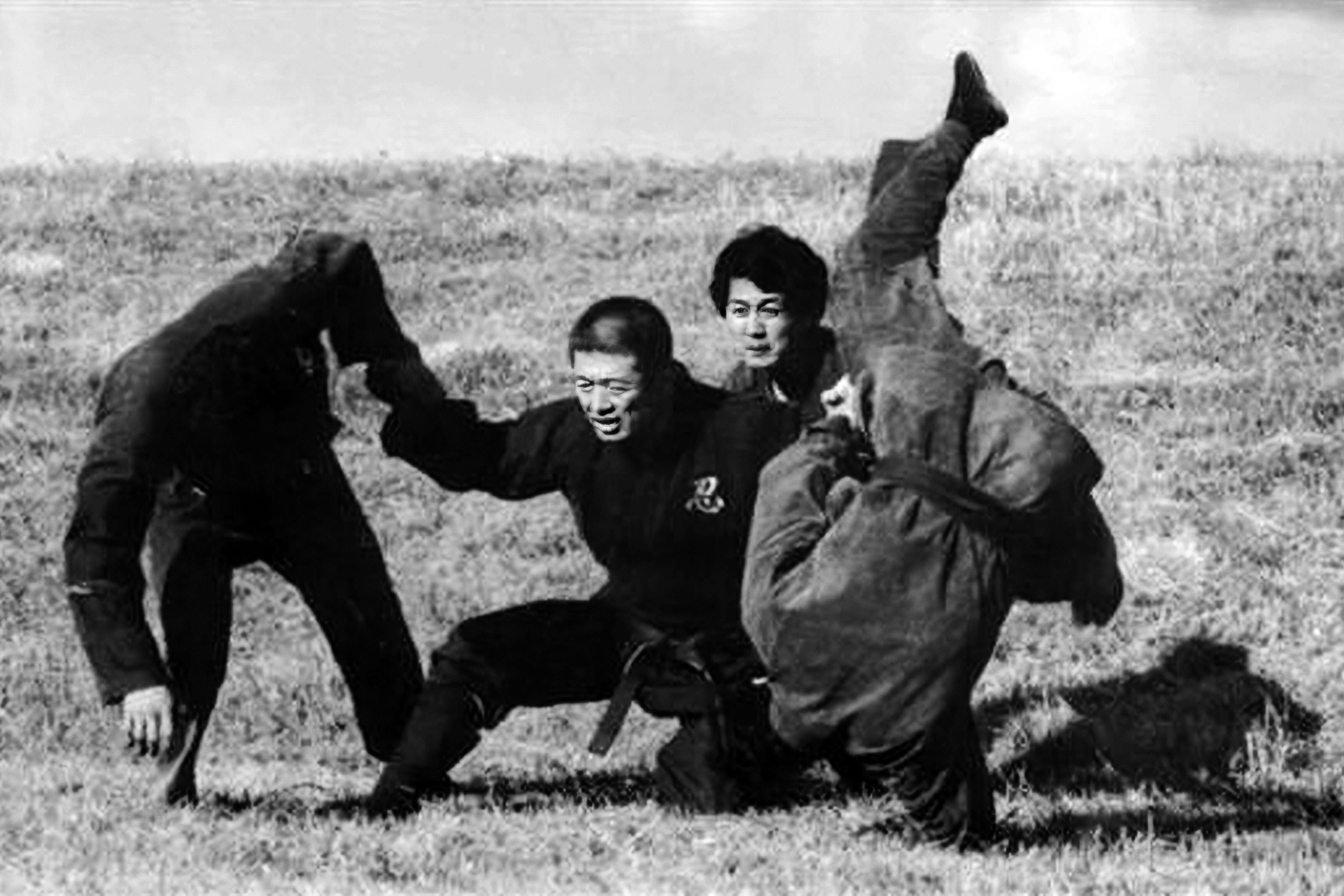

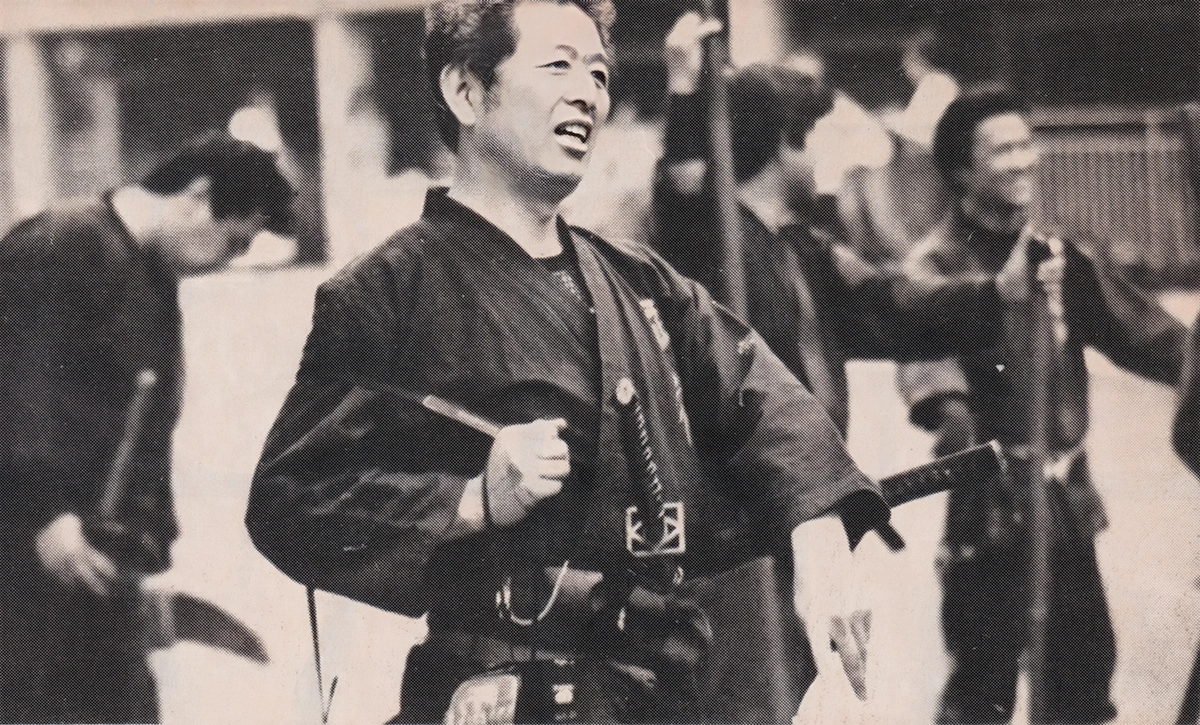

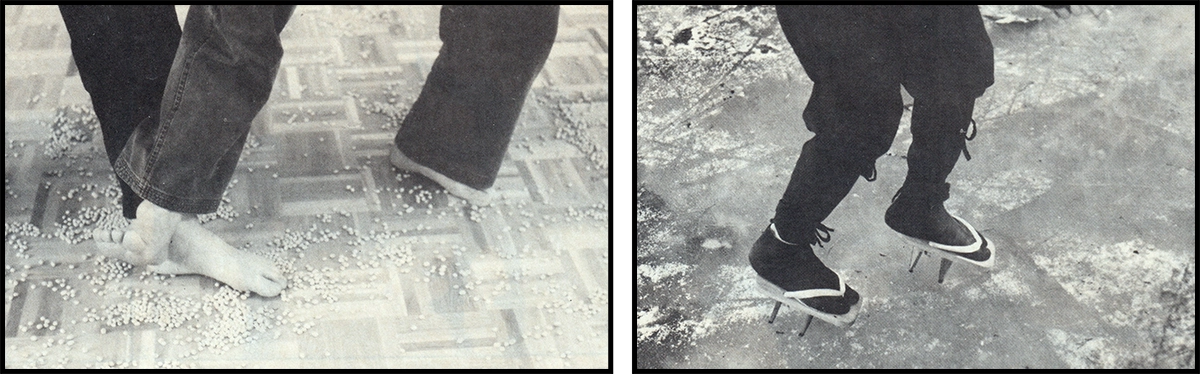

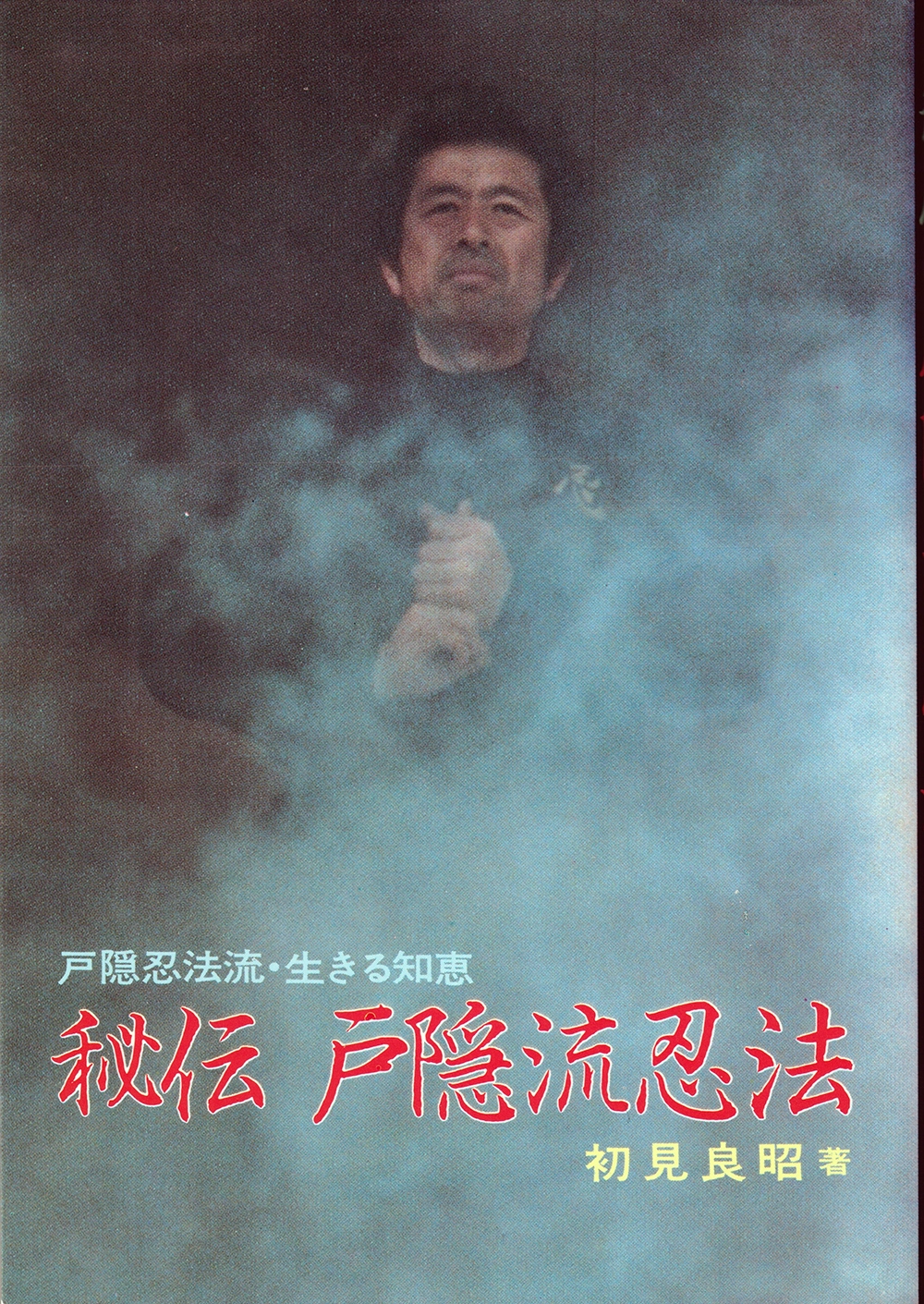

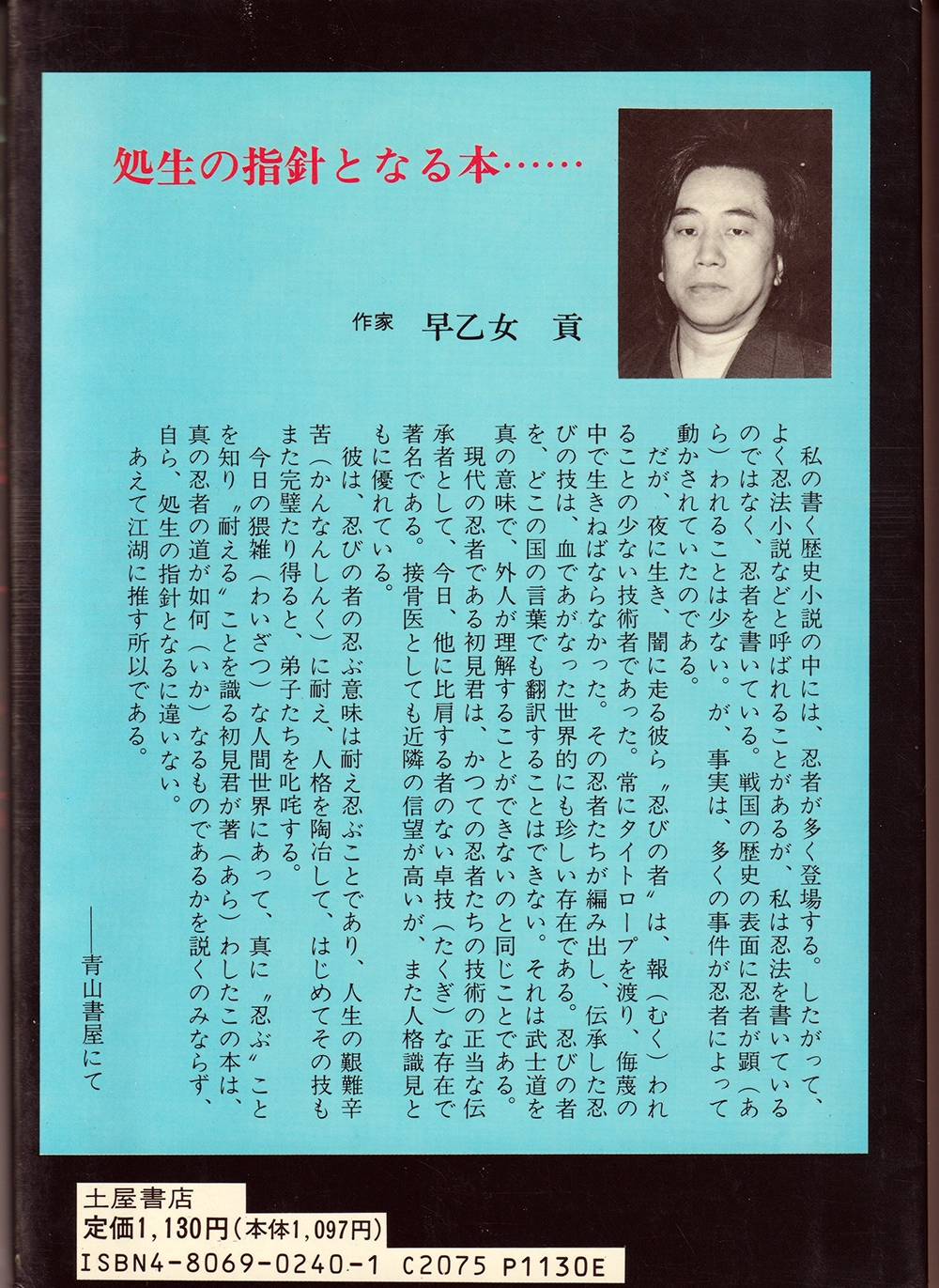

In May 1996, the serene coastal town of Noordwijkerhout in the Netherlands became the epicenter of a martial arts milestone: the Holland Taikai 1996. Over three days, martial artists from across the globe gathered to train under the legendary Masaaki Hatsumi, the 34th Sōke of the Togakure-ryū and founder of the Bujinkan organization. Organized by Mariette van der Vliet, the seminar’s theme was Kukishin-ryū Kenjutsu, the art of the sword. This event was not just about techniques—it was a celebration of adaptability, survival, and the spirit of Budō.

Setting the Stage: A Journey to Mastery

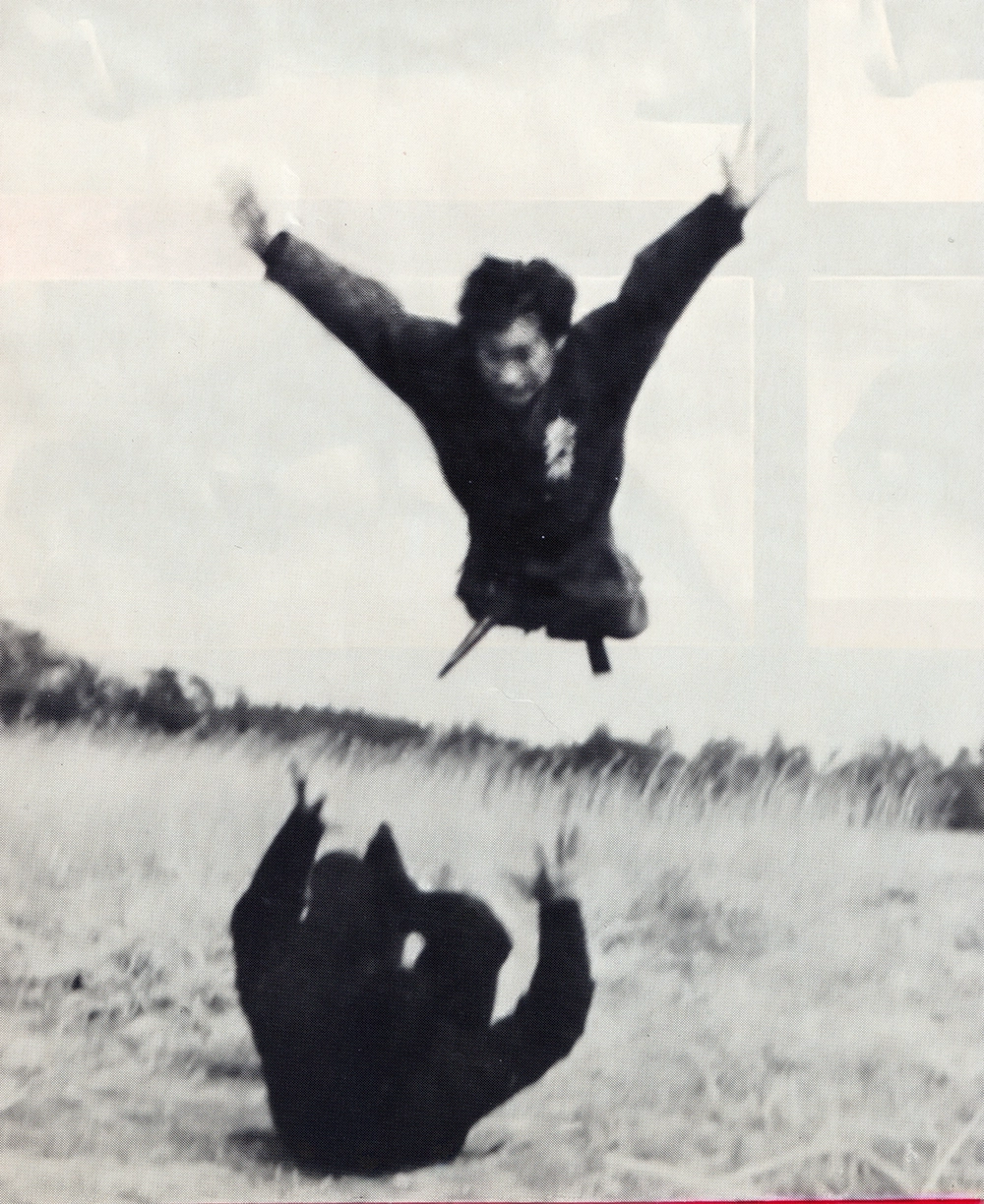

The preparation for the Holland Taikai 1996 began long before Hatsumi Sensei arrived in the Netherlands. His teaching philosophy for the year centered on Kukishin Biken Jutsu, an intricate and profound swordsmanship tradition. In April 1996, a few weeks prior to the Taikai, Hatsumi Sensei conducted an impromptu outdoor training session in Noda, Japan. He called on a select group of students, including Arnaud Cousergue, to train in the dirt outside his home.

During this session, Hatsumi Sensei emphasized the essence of Nuki Gatana (sword drawing) and the principle that form should never restrict function. He famously said:

“When things get real, do whatever you have to stay alive. Ninpō is only about surviving. Form doesn’t matter. Everything is possible.”

This philosophy would become a cornerstone of the teachings during the Holland Taikai.

The Holland Taikai: A Three-Day Immersion

From May 16 to 18, 1996, Noordwijkerhout witnessed an influx of martial artists eager to learn. Hatsumi Sensei’s sessions were renowned not only for their technical depth but also for the atmosphere of camaraderie and discovery they fostered.

Day One: The Sword’s Edge

The seminar began with a focus on the foundational techniques of Kukishin-ryū Kenjutsu. Participants practiced precise Nuki Gatana movements, emphasizing timing, positioning, and adaptability. Hatsumi Sensei encouraged students to transcend rigid forms and embrace creative application.

He explained:

“Respecting the Waza as a beginner is mandatory. But as you grow, rules are made to be broken. Adjust, adapt, and survive.”

Day Two: The Dimensions of Training

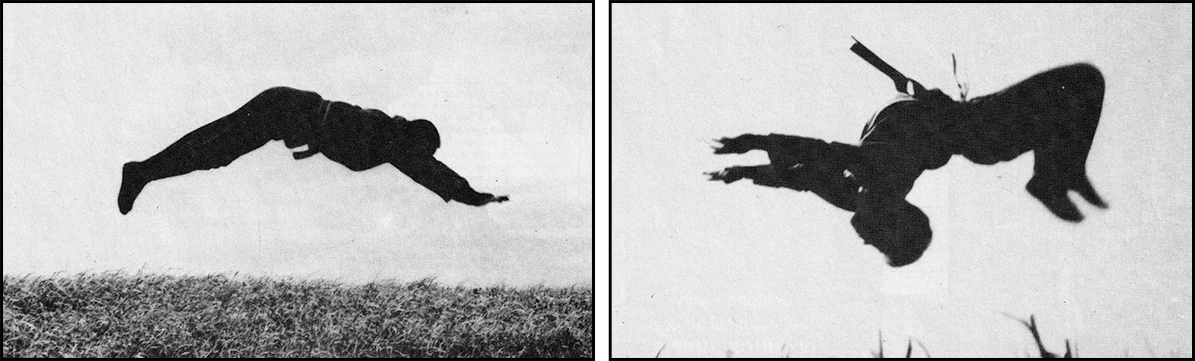

Building on the first day’s principles, Hatsumi Sensei introduced the concept of three dimensions in Budō training:

- Nijigen no Sekai (Two-dimensional world): Techniques practiced in a linear or planar fashion.

- Sanjigen no Sekai (Three-dimensional world): Expanding movements to include lateral shifts and spatial awareness.

- Yūgen no Sekai (Invisible dimension): The psychological and intuitive aspects of combat, where movements transcend physical limitations.

Through these teachings, students began to see Kukishin Biken Jutsu as more than a martial art—it was a system of infinite possibilities.

Day Three: The Invisible Path

The final day highlighted the philosophical aspects of Budō. Hatsumi Sensei shared insights into Tama, the sphere, a central concept in Japanese martial arts representing the integration of all dimensions into a cohesive whole.

Participants left with a deeper understanding that martial arts are not confined to physical techniques but are a lifelong pursuit of balance and adaptability.

Cultural Immersion and Reflection

Hatsumi Sensei’s visit to the Netherlands extended beyond the dojo. His observations during the trip added a unique cultural dimension to the event. He reflected on the country’s maritime history, symbolized by the “Tower of Tears,” where sailors’ loved ones bid them farewell. He also remarked on the Dutch people’s prowess in sports like judo and cycling, noting the nation’s emphasis on leg strength and endurance.

In an article written after the event, Hatsumi Sensei shared:

“The Netherlands is a country of Judo, isn’t it? There is a wonderful Judoka, Mr. Heesing, who speaks passionately about Judo. The mystery of Judo lies in how a smaller person can overcome a larger one—a concept deeply rooted in respect and essence.”

Key Takeaways from the Holland Taikai

- Adaptability is Survival

Hatsumi Sensei’s teachings emphasized that martial arts are not rigid but fluid. In real-life scenarios, survival depends on one’s ability to adapt and innovate beyond traditional forms. - Understanding Dimensions in Training

The progression from two-dimensional to invisible dimensions in Kukishin-ryū Kenjutsu underlined the importance of mastering fundamentals before exploring creative freedom. - Cultural Exchange

The Taikai was not only a martial arts seminar but also a bridge between Japanese and Dutch cultures, enriching participants’ perspectives on life and combat.

A Legacy That Lives On

The Holland Taikai 1996 remains a pivotal moment in the history of the Bujinkan. It demonstrated the universal appeal of Budō and its ability to transcend cultural and geographical boundaries. Hatsumi Sensei’s teachings during the seminar continue to inspire martial artists to this day, reminding them that:

“Everything is always possible.”

This philosophy, rooted in the principles of survival and adaptability, is as relevant now as it was during the Taikai.

The post The Holland Taikai 1996: A Historic Bujinkan Seminar appeared first on 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu.…