Nagase and Furuta 先生方 Japan Report Four 令和6年

From Bujinkan Santa Monica by Michael

Today I had class with Nagase and Furuta 先生方. I wake up early these days. So I made some coffee with an AeroPress in my hotel room. Then I went out to take a few street photographs. By the time I had to catch the train, I was ready for more coffee.

I installed myself at the lunch counter of a cafe. A handsome elderly woman sat next to me, drinking tea, and eating pasta. Her hair was pulled tight, and a jacket draped from her shoulders. I noted her posture with tucked elbows and a delicate use of the fork and spoon. Holding a proper teacup. I was no match for her.

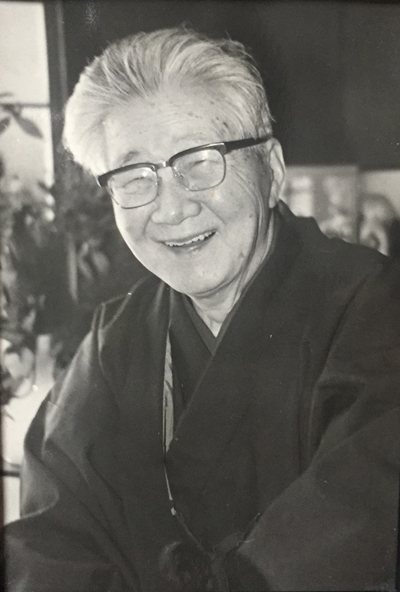

Nagase and Furuta 先生方

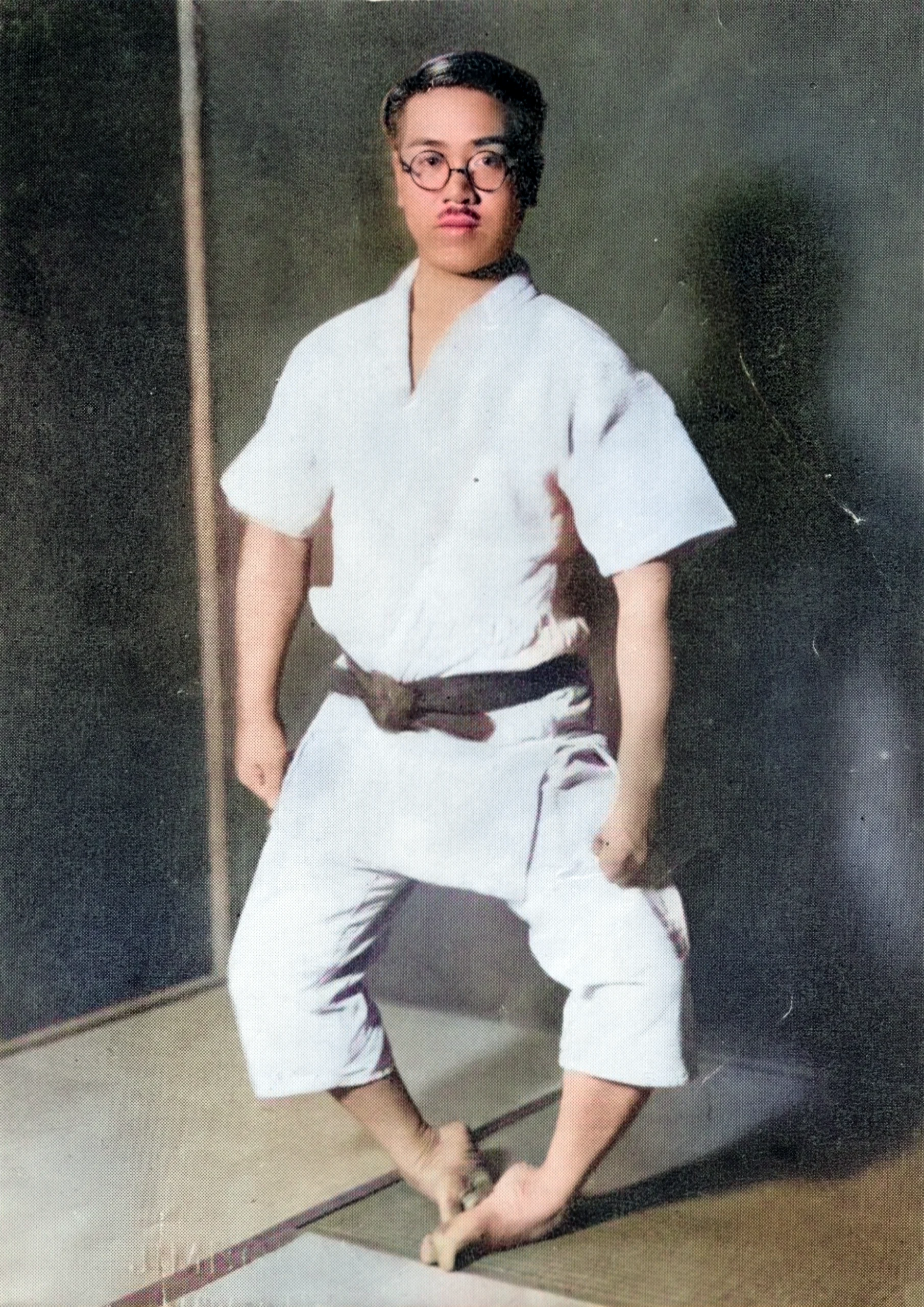

I thought about her as I rode the train to go to Nagase Sensei’s class at the Bujinkan Honbu Dojo. I normally train with him at his own Dojo, but things are more convenient now with him having classes at the Honbu. When he arrived, I helped him unload his bags from the car.

Nagase Sensei started class with a 手解 tehodoki technique leading to both 武者捕 musha dori and 武双捕 musō dori. But these techniques were concealing a vise like 竹折り take ori against his chest. I was one of the first students he demonstrated on, and it was so intense that within the first five minutes of the class I was done. He already had me in survival mode.

He continued the chain of henka off of the original technique. He described it as doing Plan A, then if that didn’t work, he did Plan B. Then he added C and D… all the way to Plan G. The last one locked the Take Ori by wrapping it with his own belt! Nagase Sensei did these all sequentially, so the opponent experienced one type of pain, and then another… and the chain never broke. Until his opponent did.

From there he began to explore three points of control from Ichimonji no Kamae. He spoke of checking or stopping the next punch. He told us this was 三心 sanshin using 上段 Jōdan, 中段 Chūdan, and 下段 Gedan… which is also 天 Ten, 地 Chi, and 人 Jin. This all becomes an infinity of 八方 Happō. If you are a long time subscriber, you may have seen me cover this theory in more detail from my other classes with Nagase Sensei.

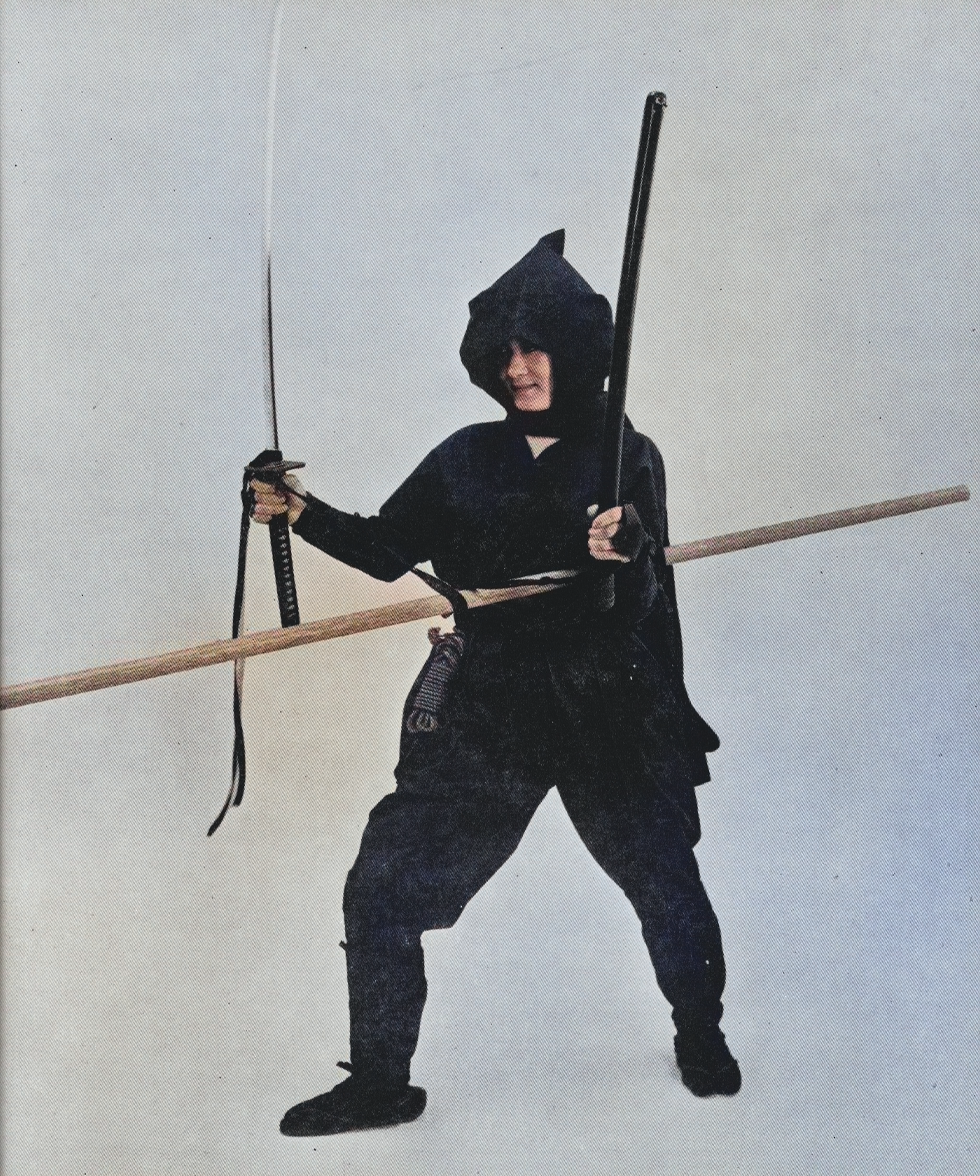

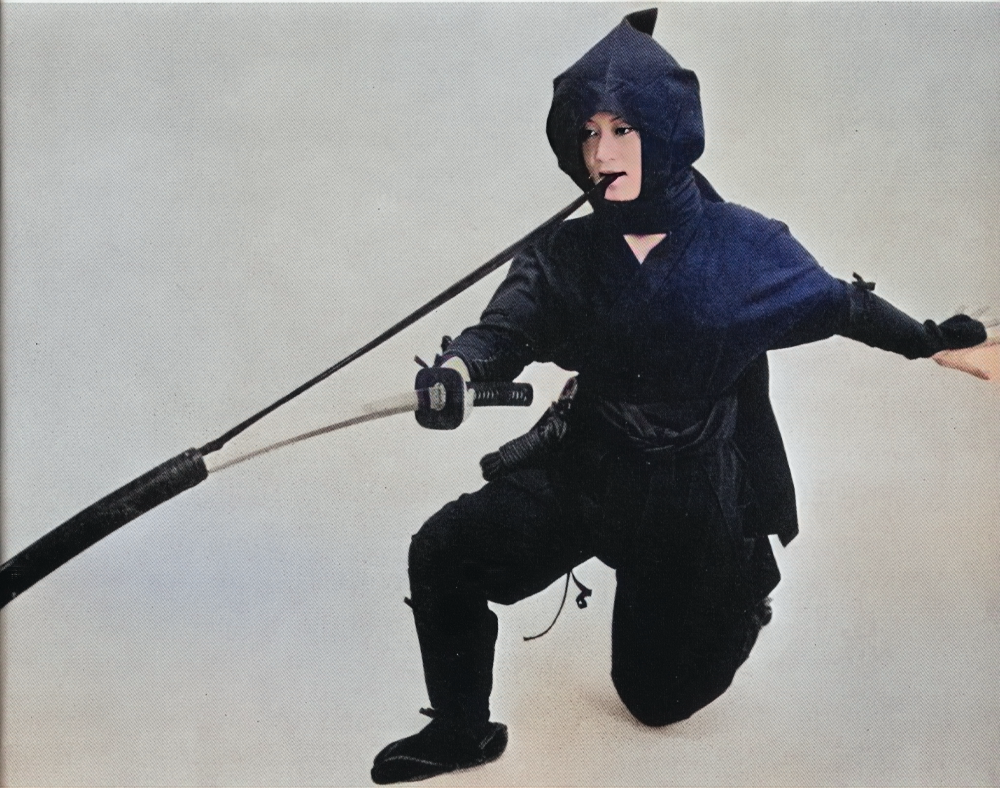

Next, Nagase demonstrated variation of tsuke iri with the hanbō. The emphasis was still on three points of control. The number three was also expressed as 無念無想の構 munen musō no kamae, 音無しの構 otonashi no kamae, and 型破の構 kata yaburi no kamae.

He extended this sanshin progression to the levels study within Bujinkan rank. From 五段 Godan you must develop your taijutsu. At 十段 Jūdan the study is mastery of bōjutsu. And then 十五段 Jūgodan must perfect kenjutsu.

I will add that not many people know that we have award levels after Jūgodan that lead up to Daishihan. I didn’t even know this until Soke gave me these awards and emphasized to me that they were to be given in order. Hatsumi Sensei has said the focus for us Daishihan is 無刀捕 mutō dori.

So Nagase Sensei finished with a kenjutsu variation on the take ori that we did earlier. I really enjoyed the class. Nagase makes me work hard as his uke. His class is one of the only sessions where I need to tap out a lot.

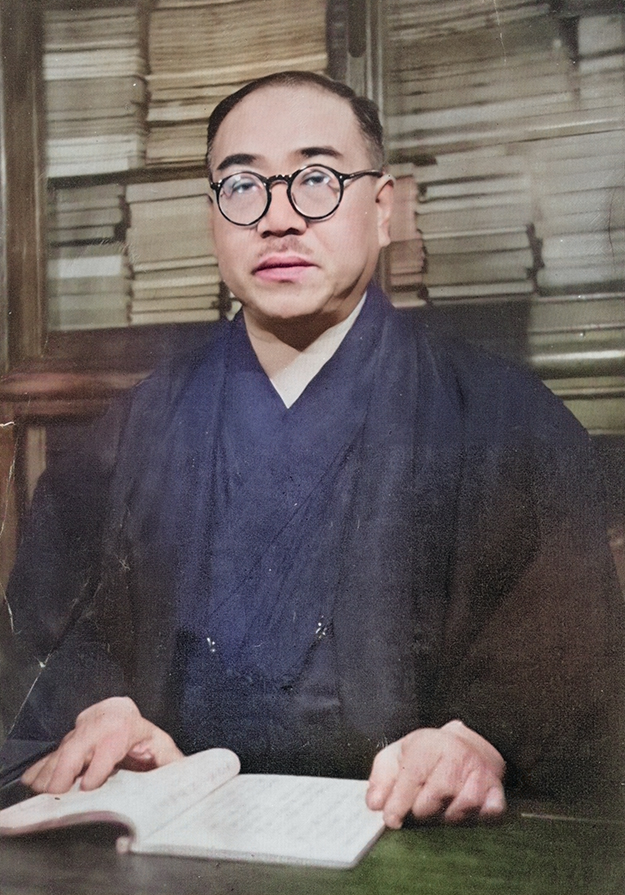

Furuta Sensei

I stepped outside for fifteen minutes to eat an おにぎり onigiri and slam some green tea. Then it was time for class with Furuta Sensei. Furuta showed up in a great mood because he had just returned from antique shopping with Hatsumi Sensei. I was happy to hear this because Soke’s health has been up and down.

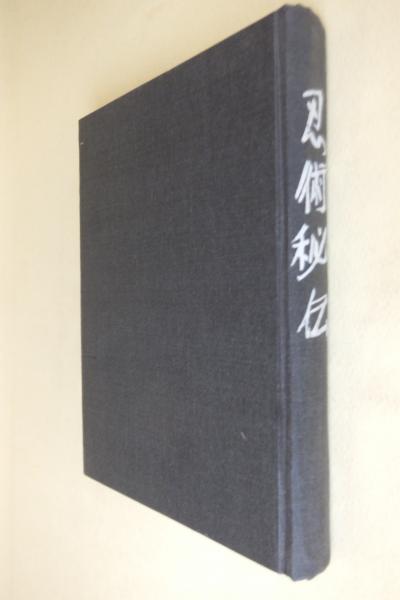

One of Soke’s favorite hobbies is shopping for antique weapons. So they went to lunch and He made Furuta Sensei buy a yari. I say “made” beause that is how Furuta described it. Hatsumi Sensei strongly recommends that Furuta buy things when they find unique weapons or artwork. Furuta said the yari didn’t even fit in his van, so he had to go back later to pick it up.

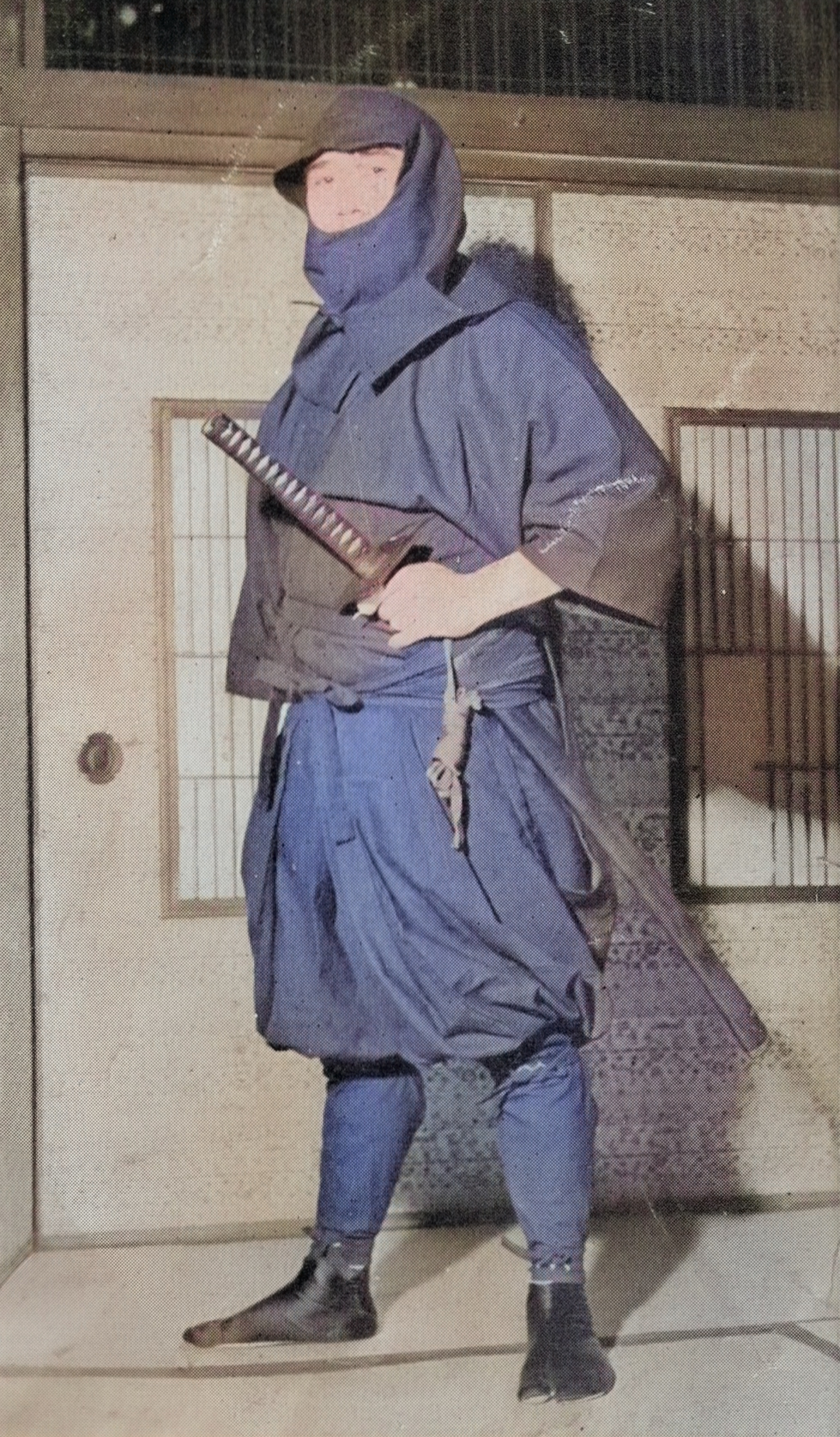

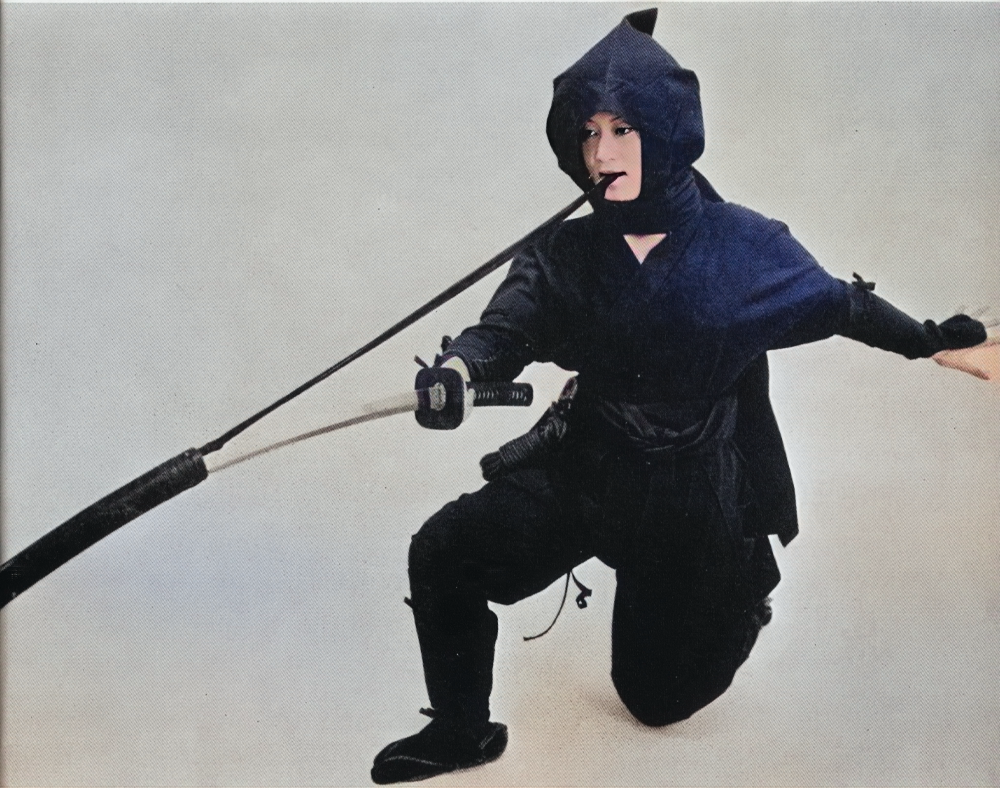

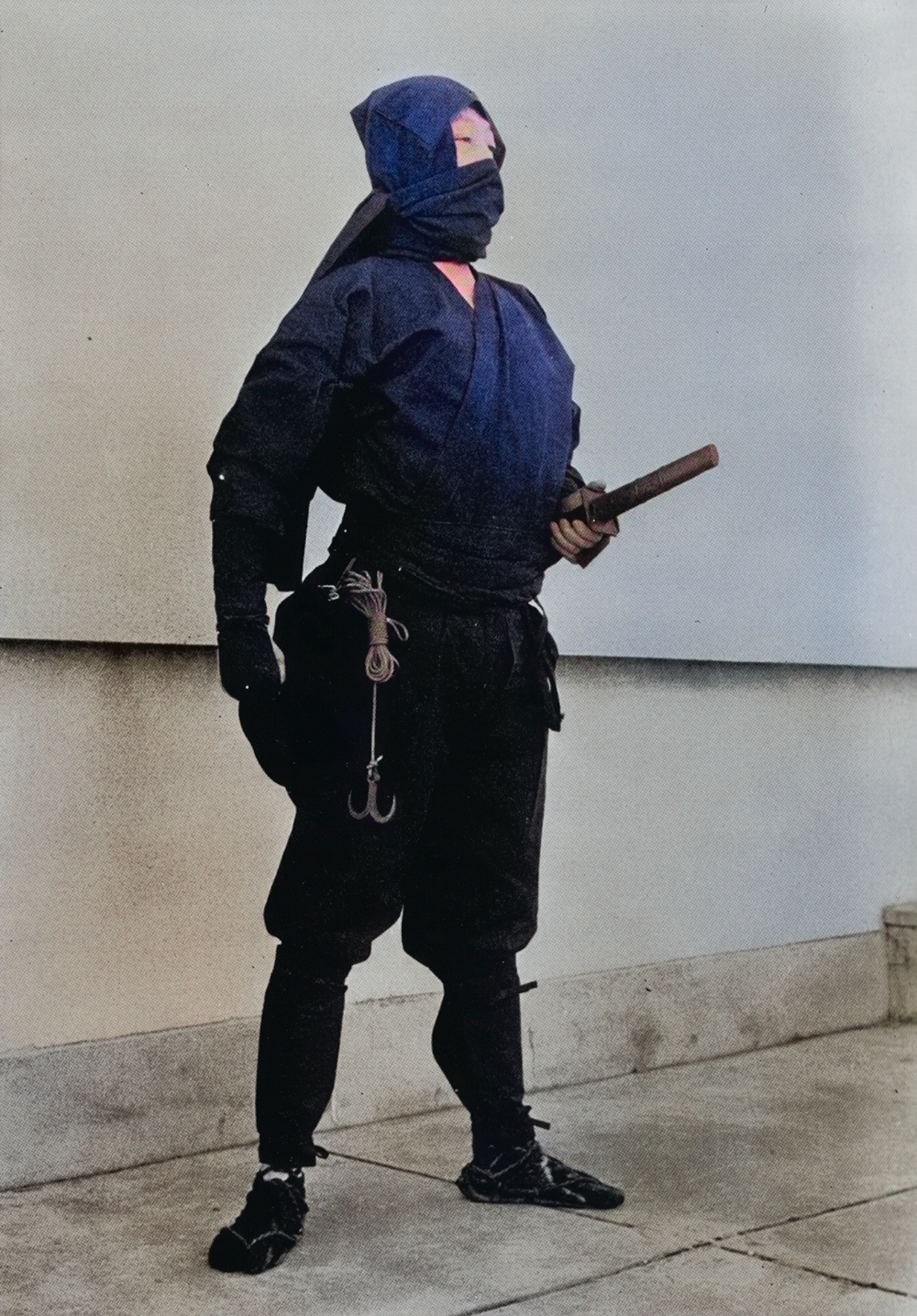

Furuta Sensei started class defending against a grab and punch. He leaned way back with his shoulder to evade. And just when the opponent adjusted to this, he would shift back the other direction and disappear. As the next Soke of 雲隠流 Kumogakure Ryū, this is an example of his approach to this school.

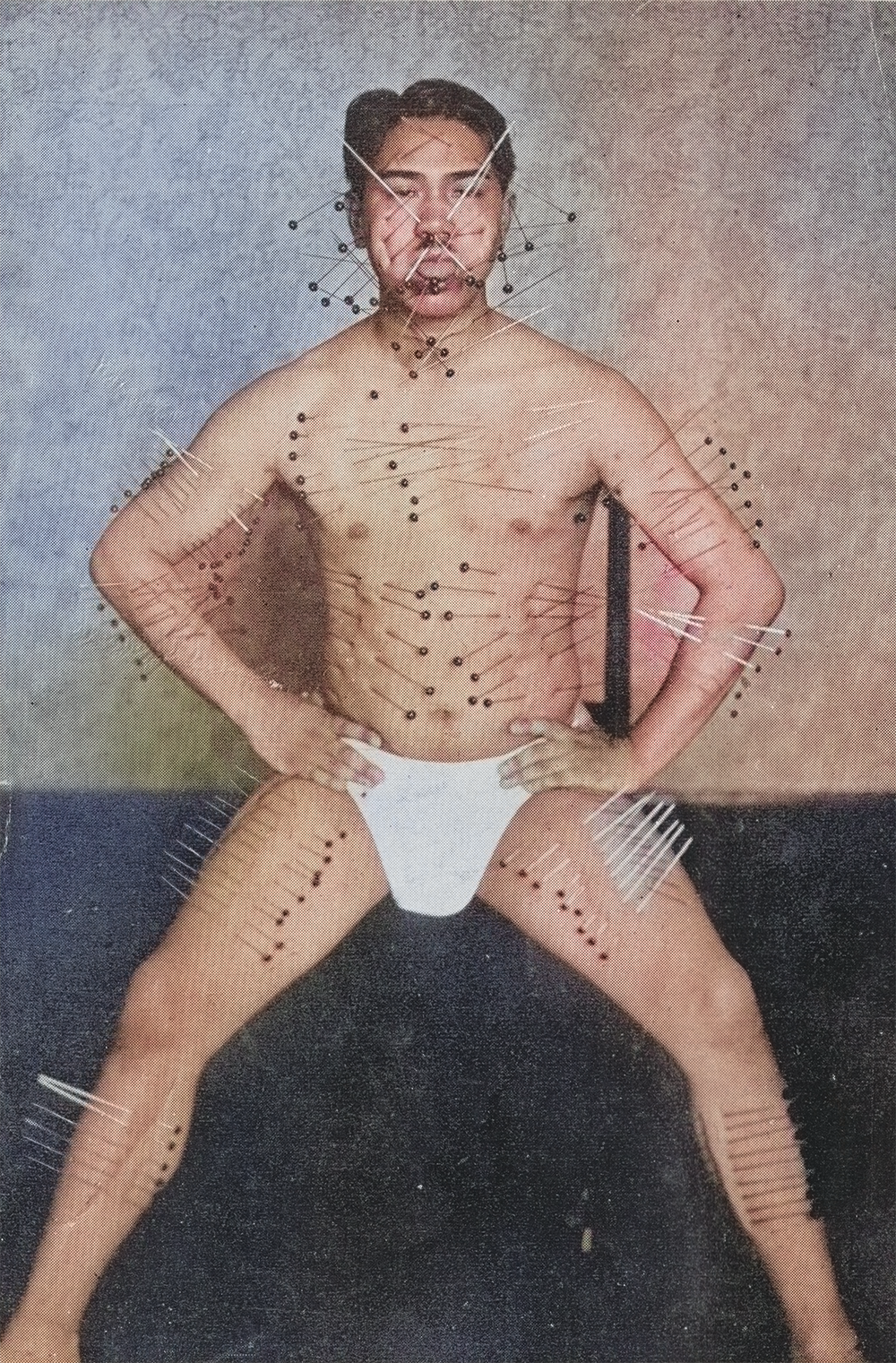

He applied a bunch of finger attacks to 急所 kyūsho on the opponent’s neck and face. Furuta Sensei then told us a story about Takamatsu Ōsensei who was attacked by a wild dog. Takamatsu stood his ground and with one finger gouged out the eye of the dog and it ran away.

Furuta did these same movements with double knives. He combined it with the kyūsho control using the fingers. But he also added throwing the knives as a distraction or to cover distance.

I find these angled evasions with the sharp and low posture that Furuta Sensei uses to be fascinating. It is very unsettling and confusing as his opponent. My normal taijutsu isn’t anything like this. Which is great because it makes me stretch and learn outside my comfort zone.

He finished class with kenjutsu from 棟水之構 Tōsui no Kamae vs a downward cut. Furuta Sensei dropped his body while his sword intercepted the cut. But he disappeared. He even dropped his own sword to disguise his escape. In that moment where he dropped away he controlled the opponent or took his weapon from him.

Finally it’s time for dinner. This is my chance to write my notes from

all of this wonderful training I did with Nagase and Furuta 先生方. I will

have another class with Furuta Sensei coming up in Japan Report Five

令和6年

…