History of Ninjutsu: List of Ninjutsu Schools

From 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu by Toryu

List of Ninjutsu Schools (Page 212-221) from the book Bessho Rekishi Dokuhon Vol. 72 – Shinobi no Mono 132-nin Data File

List of Ninjutsu Schools

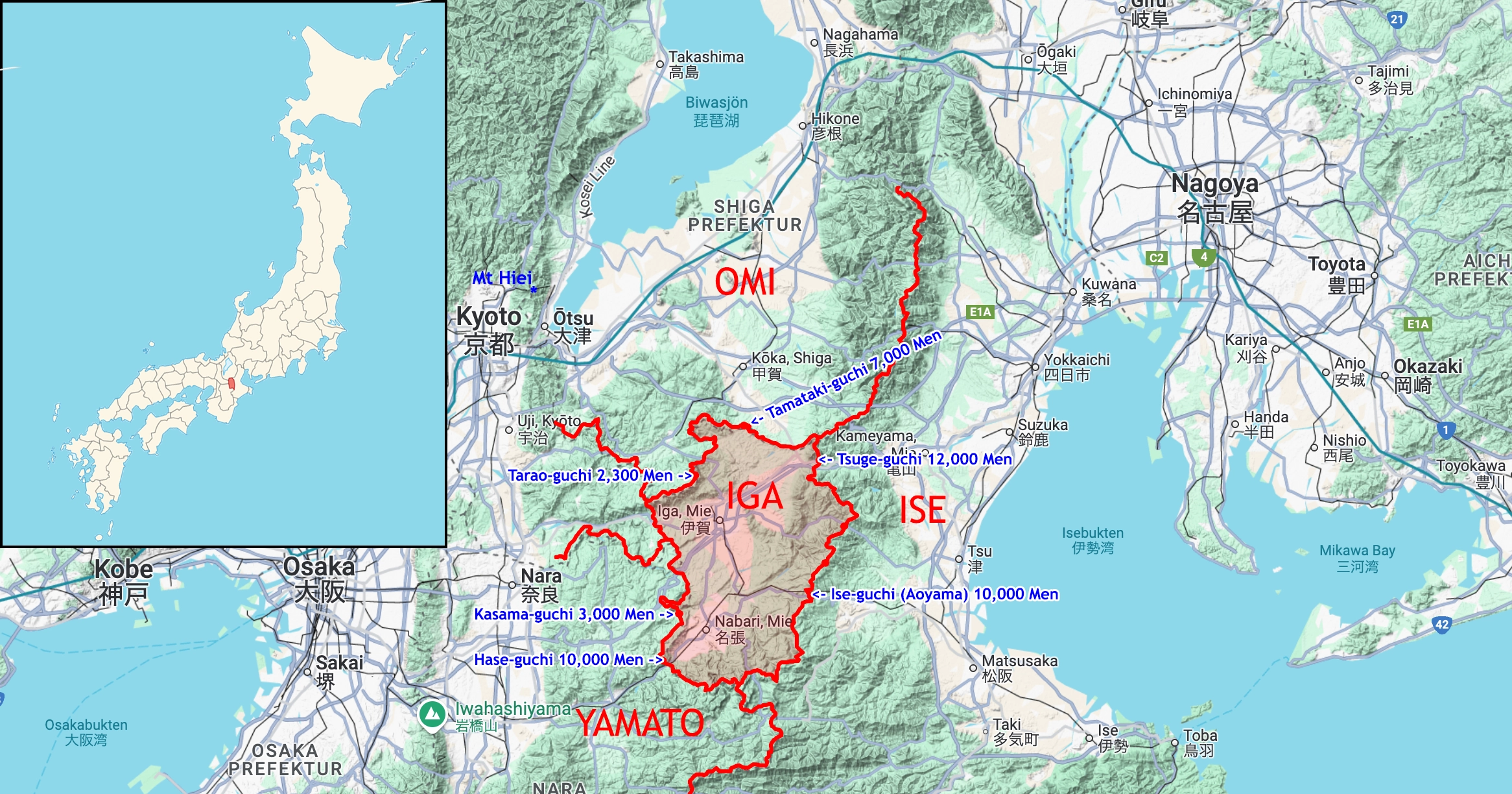

Ninjutsu (忍術 Ninjutsu) is one of the martial arts, historically used as a strategy involving espionage (候 Sō), deception (鶴計 Tsuru-kei), arson (放火 Hōka), and assassination (暗殺 Ansatsu), with examples dating back to ancient times. However, ninjutsu flourished particularly since the Sengoku period (戦国時代 Sengoku Jidai, 1467–1615), when skilled local samurai (地侍 Jizamurai) from Iga (伊賀 Iga) and Kōga (甲賀 Kōga) emerged, becoming known as 伊賀者 Igamono (Iga ninjas) and 甲賀者 Kōgamono (Kōga ninjas). They were employed by various daimyō (大名 Daimyō), established their own schools, trained disciples, developed techniques, and passed them down as secret traditions (秘伝 Hiden). One theory claims there were 73 ninjutsu schools (七十三流 Shichijūsan-ryū), but this book records over 100 schools (百余流 Hyakuyo-ryū).

The information is primarily sourced from the 増補大改訂武芸流派大事典 Zōho Daikaitei Bugei Ryūha Daijiten (Revised and Expanded Encyclopedia of Martial Arts Schools) edited by 綿谷雪 Watatani Kiyoshi. In the descriptions, the first name listed is the founder of the school. Schools labeled “unknown” (未詳 Mishō) are those whose names alone have been passed down, with little further detail.

青木流 Aoki-ryū

Associated with the 戸田家 Tōda-ke (Tōda family) of the 信濃松本領 Shinano Matsumoto-ryō (Shinano Matsumoto domain).

秋葉流 Akiba-ryū

Associated with the 尾張徳川家 Owari Tokugawa-ke (Owari Tokugawa family).

芥川流 Akutagawa-ryū

Founded by 芥川九郎右衛門義綱 Akutagawa Kurōemon Yoshitsune, also known as 刑部左衛門義任 Gyōbuzaemon Yoshitake. Part of the 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū lineage, having studied under 楠不伝正辰 Kusunoki Fuden Masatake (南木流 Nanki-ryū). In 寛文十年 Kanbun 10-nen (1670), Yoshitsune served 戸田光永 Tōda Mitsunaga of the 美濃加納領 Mino Kanō-ryō (Mino Kanō domain). As the Tōda family was reassigned, the school moved with them to 伊勢鳥羽 Ise Toba and 信濃松本 Shinano Matsumoto. The fifth-generation 義矩 Yoshinori and sixth-generation 極人 Kyokuto (father and son) were implicated in the 戸田図書事件 Tōda Zusho Jiken (Tōda Zusho Incident), a family dispute during the late 天保年間 Tenpō Gannen (1830–1844).

伊賀崎流 Igasaki-ryū

Founded by 伊賀崎孫太夫道順 Igasaki Magotayū Dōjun, the head of the 49 Iga schools (伊賀四十九流 Iga Shijūku-ryū).

伊賀流 Iga-ryū

Iga ninjas are known for their individual strength over group cohesion, with a particular emphasis on the use of fire. It’s said that if explosives (爆薬 Bakuyaku) were used, Iga ninjas were likely involved. The founder of Iga-ryū is traditionally considered to be 服部家長 Hattori Ienaga from the late 平安時代 Heian Jidai (Heian period). According to 吉田東伍 Yoshida Tōgo’s 大日本地名辞書 Dai Nihon Chimei Jisho (Great Japanese Place Names Dictionary), the Iga group (伊賀衆 Iga-shū or 伊賀者 Igamono) was a faction of low-ranking bannermen under the 徳川氏 Tokugawa-shi (Tokugawa clan), likely due to their service since 徳川家康 Tokugawa Ieyasu’s “Iga crossing” (伊賀越え Iga-goe).

The Iga ninja 服部半蔵 Hattori Hanzō is said to be a descendant of the 秦氏 Hata-shi (Hata clan), immigrants from 百済 Baekje who settled in Iga.

During the 永禄年間 Eiroku Gannen (1558–1570), 11 exceptional Iga ninjas were noted:

- 新堂の小太郎 Shindō no Kotarō

- 下柘植の木猿 Shimotsuge no Mokuzaru

- 同子猿 Dō Kozaru (Mokuzaru’s son)

- 山田の八右衛門 Yamada no Hachiemon

- 神戸の小南 Kobe no Konami

- 音羽の城戸 Otowa no Jōto

- 甲山の太郎四郎 Kōyama no Tarōshirō

- 同太郎左衛門 Dō Tarōzaemon (also of Kōyama)

- 野村の大炊孫大夫 Nomura no Ōisunadayū

- 上野の左 Ueno no Sō

There’s also a school called 服部流 Hattori-ryū.

伊賀流 Iga-ryū

Associated with the 土佐山内家 Tosa Yamauchi-ke (Tosa Yamauchi family), including 服部正信 Hattori Masanobu and other members of the 服部氏 Hattori-shi (Hattori clan).

伊賀流 Iga-ryū

Founded by 滝野定勝 Takino Sadakatsu, followed by 赤井田重勝 Akaida Shigetake, among others.

伊賀流 Iga-ryū

Also known as 北条流 Hōjō-ryū (listed separately). Based on the guerrilla tactics of the 関東乱波風魔一族 Kantō Ranba Fūma Ichizoku (Kantō Ranba Fūma clan).

一全流 Ichizen-ryū

Founded by 近松彦之進茂矩 Chikamatsu Hikonoshin Shigenori. Shigenori studied 伊賀流 Iga-ryū under 竹之下頼美 Takenoshita Yorimi of 伊賀四日市 Iga Yokkaichi and 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū under 木村康敬 Kimura Yasutake of 近江 Ōmi. He passed away in 安永七年 An’ei 7-nen (1772). The school emphasized rapid horseback travel, aiming for a daily speed of 六十里 Rokujūri (approximately 240 km).

一佐流 Issa-ryū (吉佐流 Kissa-ryū)

Founded by 佐々木三郎兵衛盛綱 Sasaki Saburōbei Moritsune. He learned techniques from a foreign master, 我桂仙 Waga Keisen, and it’s said only three families in Japan used these methods. The sixth-generation successor, 黒見勝五郎 Kuromi Katsugorō, received permission in 元治元年 Genji 1-nen (1864).

伊賀流 Iga-ryū

Associated with the 信濃松本領 Shinano Matsumoto-ryō (Shinano Matsumoto domain).

上杉流 Uesugi-ryū

Founded by 上杉謙信 Uesugi Kenshin, passed down through his retainer 宇佐美定行 Usami Sadayoshi.

内山流 Uchiyama-ryū

Associated with 伊勢 Ise.

越前流 Echizen-ryū

After the 伊賀の乱 Iga no Ran (Iga Rebellion) of 天正九年 Tenshō 9-nen (1581), Iga ninjas served the 前田家 Maeda-ke (Maeda family) and passed down their traditions.

御家流 Oie-ryū

Founded by 東忠次 Azuma Tadatsugu, followed by 東太郎左衛門 Azuma Tarōzaemon, then 城戸長次 Jōto Chōji.

大井流 Ōi-ryū

Founded by 大井孫太夫 Ōi Magotayū, also known as 大炊 Ōi. Said to be from either 伊賀野村 Iga Nomura or 和泉 Izumi.

応変流 Ōhen-ryū

Associated with the 仙台伊達家 Sendai Date-ke (Sendai Date family).

加治流 Kaji-ryū

Founded by 加治遠江守景英 Kaji Tōtōmi-no-Kami Kagehide, a disciple of 宇佐美定行 Usami Sadayoshi under 上杉謙信 Uesugi Kenshin. Possibly part of the 伊賀流服部党 Iga-ryū Hattori-tō (Iga-ryū Hattori faction).

上泉流 Kamiizumi-ryū

Founded by 上泉常陸介秀胤 Kamiizumi Hitachi-no-Suke Hidekane, the legitimate son of 上泉伊勢守信綱 Kamiizumi Ise-no-Kami Nobutsuna. He accompanied his father on martial training journeys across the country, later serving the 北条氏 Hōjō-shi (Hōjō clan) and fighting against the 里見軍 Satomi-gun (Satomi army). In 永禄七年 Eiroku 7-nen (1564), he died from injuries sustained in battle. 信綱 Nobutsuna adopted a successor who took the name 秀胤 Hidekane. The school was passed down to the 岡山池田家 Okayama Ikeda-ke (Okayama Ikeda family) and the 彦根井伊家 Hikone Ii-ke (Hikone Ii family). Its secret manual is 師鑑専要 Shikan Sen’yō.

上柘植氏流 Kamitsuge-shi-ryū

Part of the 伊賀流 Iga-ryū lineage. Details otherwise unknown.

蒲生流 Gamō-ryū

Passed down through the 蒲生家 Gamō-ke (Gamō family) of 伊勢 Ise, 近江 Ōmi, and later 陸奥 Mutsu.

紀州流 Kishū-ryū

According to the 戸隠流口伝書 Togakure-ryū Kuden-sho (Togakure-ryū Oral Tradition Manual), the 白雲流 Hakun-ryū that entered the 熊野三山 Kumano Sanzan (three sacred mountains of Kumano) evolved into 紀州流 Kishū-ryū through 修験者 Shugenja (Shugendō practitioners). Alternatively, it’s said to be a school formed by Iga ninjas who fled to 紀伊 Kii’s 根来 Negoro (雑賀 Saiga) after their defeat in the 伊賀の乱 Iga no Ran (Iga Rebellion) of 天正九年 Tenshō 9-nen (1581).

九州流 Kyūshū-ryū

Passed down through the family of 志賀如見斎 Shiga Nyomisai, the third-generation master of 本心刀流 Honshinto-ryū (a swordsmanship school).

Founded by 戸田左京一心斎 Tōda Sakyō Isshinsai. The school was passed to 百地三太夫 Momochi Sandayū and continued within 伊賀流 Iga-ryū, reaching 戸田真竜軒 Tōda Shinryūken by the end of the Edo period.

楠流 Kusunoki-ryū

Originating from 楠木正成 Kusunoki Masashige of the 南北朝時代 Nanbokuchō Jidai (Nanbokuchō period, 1336–1392). Masashige, a local lord from 河内 Kawachi (eastern 大阪府 Osaka-fu, Osaka Prefecture), used 山伏兵法 Yamabushi Heihō (mountain ascetic military tactics) in various battles. He excelled in guerrilla warfare but later died in battle against 足利尊氏 Ashikaga Takauji during a campaign in the capital.

Founded by 伊賀平右衛門家長 Iga Heiemon Ienaga (雲隠法師 Kumogakure Hōshi).

Lineage: 戸田真竜軒 Tōda Shinryūken → 高松寿嗣 Takamatsu Toshitsugu → 初見良昭 Hatsumi Yoshiaki.

鞍馬揚心流 Kurama Yōshin-ryū

Founded by 塩田甚太夫 Shiota Jintayū. Also known as 塩田揚心流 Shiota Yōshin-ryū. In 安永九年 An’ei 9-nen (1780), it was established by combining 揚心流 Yōshin-ryū and 鈴木流 Suzuki-ryū. Passed down in 薩摩飯島 Satsuma Iijima.

黒田流 Kuroda-ryū

Associated with the 筑前福岡藩 Chikuzen Fukuoka-han (Chikuzen Fukuoka domain), founded by 黒田官兵衛孝高 Kuroda Kanbei Takayoshi (如水 Nyosui). The 黒田氏 Kuroda-shi (Kuroda clan) is a branch of the 近江源氏佐々木高綱 Ōmi Genji Sasaki Takatsuna line, originating from 黒田郷 Kuroda-gō in 近江国 Ōmi-koku (滋賀県 Shiga-ken, Shiga Prefecture). Due to their connection with 和田伊賀守惟政 Wada Igamori Tadamasa of the 甲賀五十三家 Kōga Gojūsan-ke (Kōga 53 families), a close associate of the 15th shogun 足利義昭 Ashikaga Yoshiaki, 甲賀流忍術 Kōga-ryū Ninjutsu is said to have influenced Kanbei’s military strategies. A famous story involves 栗山善助 Kuriyama Zensuke, who frequently visited his imprisoned lord in disguise. Later, two ninjas were reportedly dispatched to assassinate 後藤又兵衛 Gotō Matabei.

現実流 Genjitsu-ryū

A branch of 白雲流 Hakun-ryū.

源瀟 Gensō

A branch of 永雲流 Eiun-ryū.

甲賀流 Kōga-ryū

The 武芸流派大事典 Bugei Ryūha Daijiten notes that both 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū and 伊賀流 Iga-ryū have too many speculative theories regarding their founders and lineages. While I’d prefer to follow this stance, it’s not entirely feasible. The distinction between 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū and 伊賀流 Iga-ryū itself is a point of contention, likely beginning in the 戦国時代 Sengoku Jidai (Sengoku period) for several reasons:

- 甲賀 Kōga and 伊賀 Iga are geographically adjacent.

- Both regions are similarly surrounded by mountains.

- The characters for 伊賀 Iga (伊賀) and 甲賀 Kōga (甲賀), when written in cursive script (草書 Sōsho), can appear similar.

In 長享元年 Chōkyō 1-nen (1487), when 六角高頼 Rokaku Takayoshi fought against 足利義尚 Ashikaga Yoshihisa, the rural samurai of 甲賀 Kōga sided with the 六角方 Rokaku-hō (Rokaku faction) due to longstanding ties. This marked the origin of the 甲賀五十三家 Kōga Gojūsan-ke (Kōga 53 Families). Later that year, in October, during the battle at 鏡安養寺 Kagami Anyōji, 21 of these 53 families distinguished themselves, earning the designation 甲賀二十一家 Kōga Nijūikkake (Kōga 21 Families) and the privilege to bear surnames and carry swords. The lower-ranking ninjas (下忍 Genin) operated under this organization.

The 21 families within the 53 are:

北山九家 Kitayama Ku-ke (Kitayama Nine Families)

- 黒川久内 Kurokawa Hisanai

- 大河原源太 Ōgawara Genta

- 頓宮四方介 Tongū Shihōsuke

- 土山鹿之助 Tsuchiyama Shikanotsume

- 芥川左京亮 Akutagawa Sakyōryō

- 望月出雲守 Mochizuki Izumo-no-Kami

- 岩室大学介 Iwanomura Daigakusuke

- 佐治河内守 Saji Kōchi-no-Kami

- 神保兵内 Jinbo Hyōnai

南山六家 Minamiyama Roku-ke (Minamiyama Six Families)

- 大原源三郎 Ōhara Genzaburō

- 和田伊賀守 Wada Igamori

- 上野主膳正 Ueno Shuzen-no-Shō

- 高峰蔵人 Takamine Kurōdo

- 滝(多喜)勘八郎 Taki (Taki) Kanpachirō

- 池田庄右衛門 Ikeda Shōemon

庄内三家 Shōnai San-ke (Shōnai Three Families)

- 鵜飼源八郎 Ukai Genpachirō

- 三雲新蔵人 Mikumo Shinzōto

- 内貴伊賀守 Naiki Igamori

柏木三家 Kashiwagi San-ke (Kashiwagi Three Families)

- 伴左京介 Ban Sakyōsuke

- 山中十郎 Yamanaka Jūrō

- 美濃部源吾 Minobe Gengo

The remaining 32 families, making up the 甲賀五十三家 Kōga Gojūsan-ke (Kōga 53), are:

- 饗庭河内守 Aiba Kōchi-no-Kami

- 青木筑後守 Aoki Chikugo-no-Kami

- 岩根長門守 Iwane Nagato-no-Kami

- 上田三河守 Ueda Mikawa-no-Kami

- 宇田藤内 Uda Tōnai

- 大久保源内 Ōkubo Gen’nai

- 大野宮内少輔 Ōno Kinai-shōsuke

- 隱岐右近太夫 Oki Ukon-tayū

- 小川孫十郎 Ogawa Sonjūrō

- 葛城丹後守 Katsuragi Tango-no-Kami

- 上山新八郎 Ueyama Shinpachirō

- 儀俄越前守 Giga Echizen-no-Kami

- 倉次右近介 Kuraji Ukon-no-Suke

- 小泉外記 Koizumi Gaiki

- 高山源太左衛門 Takayama Genta-Zaemon

- 新庄越後守 Shinjō Echigo-no-Kami

- 杉谷与藤次 Sugitani Yōtoji

- 杉山八郎 Sugiyama Hachirō

- 高野備後守 Takano Bingo-no-Kami

- 多罹尾四郎兵衛 Tarōbei Taro

- 鳥居兵内 Torii Hyōnai

- 長野刑部丞 Nagano Gyōbu-no-Jō

- 中山民部丞 Nakayama Minbu-no-Jō

- 夏見大学 Natsumi Daigaku

- 野田五郎 Noda Gorō

- 服部藤太夫 Hattori Tōtayū

- 八田勘助 Hata Kanpachirō

- 針和泉守 Hari Izumi-no-Kami

- 平子主殿介 Hirako Shuden-no-Suke

- 牧村右馬介 Makimura Uma-no-Suke

- 宮島掃部介 Miyajima Kamonnosuke

- 山上藤七郎 Yamagami Tōshichirō

Under these 53 mid-ranking ninjas (中忍 Chūnin), there were lower-ranking ninjas (下忍 Genin) from branch families. During the 戦国時代 Sengoku Jidai (Sengoku period), it’s said that 300 to 400 Kōga ninjas were employed by various domains across the country.

甲賀流和田流 Kōga-ryū Wada-ryū

和田伊賀守惟政 Wada Igamori Tadamasa. One of the 南山六家 Minamiyama Roku-ke (Minamiyama Six Families) within the 甲賀五十三家 Kōga Gojūsan-ke (Kōga 53 Families).

郷家流 Gōke-ryū

Refers to the Wada faction within 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū.

高山流 Takayama-ryū (甲山流 Kōyama-ryū)

Founded by 高山四郎右衛門 Takayama Shirōemon.

甲州流 Kōshū-ryū

Also known as 信玄流 Shingen-ryū, 武田流 Takeda-ryū, or 甲陽流 Kōyō-ryū. It evolved as an independent espionage division from military strategy (兵法 Heihō). In the 武田氏 Takeda-shi (Takeda clan), ninjas were called 三ツ者 Mitsumono.

Additionally, there are 忍光流 Ninkō-ryū and 忍甲流 Ninkō-ryū, both of which are in the same lineage as 武田流軍学 Takeda-ryū Gungaku (Takeda-ryū military science).

上月流 Kōzuki-ryū

Founded by 上月佐助 Kōzuki Sasuke, said to be the model for 猿飛佐助 Sarutobi Sasuke.

甲陽軍鑑的流 Kōyō Gunkan-teki-ryū

A branch of 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū. Founded by 大原数馬 Ōhara Sūma.

甲陽流 Kōyō-ryū

Founded by 武田倉玄 Takeda Sōgen. On the orders of 倍玄 Baigen, 山県三郎兵衛 Yamagata Saburōbei and 武藤喜兵衛 Mutō Kibei jointly taught the techniques to a few individuals, including 山本勘介 Yamamoto Kansuke. A branch of 甲州流 Kōshū-ryū. It was passed down to 禰津数馬 Netsu Sūma of the 松代領真田家 Matsushiro-ryō Sanada-ke (Matsushiro domain Sanada family) under 信濃 Shinano and continued until the end of the Edo period.

五遁十方万流 Gotōn Juppō Man-ryū

A branch of 白雲派 Hakun-ha.

小隼人流 Kohayato-ryū

Founded by 中川小隼人綜貞 Nakagawa Kohayato Sōtei (中川流 Nakagawa-ryū).

雑賀流 Saiga-ryū

Passed down in 紀伊雑賀 Kii Saiga.

西法院武安流 Saigakuin Buan-ryū

Founded by 村田太郎右衛門重家 Murata Tarōemon Shigeie during the 慶長年間 Keichō Gannen (1596–1615). Passed down in the 仙台伊達家 Sendai Date-ke (Sendai Date family).

三刀流 Santō-ryū

Said to originate from 佐々木某 Sasaki Bō of 山城 Yamashiro.

塩田揚心流 Shiota Yōshin-ryū

Founded by 塩田甚太夫 Shiota Jintayū. In 安永九年 An’ei 9-nen (1780), he learned 場心流 Bashin-ryū from 中田元随 Nakada Mototsume of 肥前 Hizen (佐賀 Saga and 長崎 Nagasaki), combined it with 鈴木流 Suzuki-ryū, and established the school. Later renamed 鞍馬揚心流 Kurama Yōshin-ryū.

神道流 Shintō-ryū

Founded by 飯篠長威斎家直 Iishino Chōisai Ienao or 尊胤 Sontake. Officially called 天真正伝香取神道流 Tenshō Jisshōden Katori Shintō-ryū, often abbreviated to 香取神道流 Katori Shintō-ryū. This school is a comprehensive martial art, with its swordsmanship (剣術 Kenjutsu) passed down through 塚原安幹 Tsukahara Yasutake to 塚原ト伝 Tsukahara Tōden.

神秘洋 Shinpiyō

Founded by 小林妙現 Kobayashi Myōgen. Known as 神仙術 Shinsensjutsu (Taoist immortal techniques), acquired in 昭和十一年 Shōwa 11-nen (1936) from 高野源八郎峰洞 Takano Genpachirō Hōdō. Includes spiritual magic techniques such as rope-breaking (断縄 Dannawa), iron (鉄 Tetsu), needle-walking (針行 Hari-gyō), hand-wax (手蠟 Terō), and tile-breaking (破瓦 Haga).

新楠流 Shinkusunoki-ryū

Founded by 名取三十郎正澄 Natori Sanjūrō Masazumi. Also called 名取流 Natori-ryū.

全流 Zen-ryū

Founded by 徳川吉通 Tokugawa Yoshimichi. Officially called 武道全流道しるべの伝 Budō Zen-ryū Michishirube no Den. Yoshimichi was the fourth-generation head of the 尾張徳川家 Owari Tokugawa-ke (Owari Tokugawa family).

大気流 Taiki-ryū

Founded by 塚田紫雲斎 Tsukada Shiunsai (fifth generation).

滝野流 Takino-ryū

Founded by 滝野半九郎定勝 Takino Hankurō Sadakatsu.

滝流 Taki-ryū

Founded by 滝不雪 Taki Fuyuki during the 貞享年間 Jōkyō Gannen (1684–1688). Said to have been established by combining 伊賀 Iga and 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū.

琢磨流 Takuma-ryū

A lineage of 武田竜芳 Takeda Ryūhō (the second son of 勝頼 Katsuyori, of the 海野氏 Umino-shi).

武田流 Takeda-ryū

A lineage of 甲州流 Kōshū-ryū.

多羅尾流 Tarao-ryū

Founded by 多羅尾四郎兵衛光広 Tarao Shirōbei Mitsuhiro. One of the 甲賀五十三家 Kōga Gojūsan-ke (Kōga 53 Families).

忠孝心貫流 Chūkō Shinkan-ryū

Founded by 平山行蔵 Hirayama Gyōzō, an 伊賀同心 Iga Dōshin (Iga agent). He mastered 心貫流 Shinkan-ryū and established this school. He set up a dojo in 四谷伊賀町 Yotsuya Iga-chō, training unique disciples such as 吉里香敵斎 Yoshisato Kateki, 相馬大作 Sōma Daisaku, and 勝小吉 Katsu Kogichi.

柘植流 Tsuge-ryū

Refers to the ninjutsu of the 柘植党 Tsuge-tō (Tsuge faction) within 伊賀流 Iga-ryū.

天幻流 Tengen-ryū

Founded by 大月八兵衛 Ōtsuki Hachibei, a retainer of the 甲斐武田家 Kai Takeda-ke (Kai Takeda family).

天遁八方流 Tenton Happō-ryū

A branch of 白雲流 Hakun-ryū.

当流 Tō-ryū

Same as 滝野流 Takino-ryū.

Said to originate from 戸田真竜軒 Tōda Shinryūken. During the 養和年間 Yōwa Gannen (1181–1182), it branched off from 白運道士 Hak’un Dōshi’s 白雲流 Hakun-ryū. It passed through 百地三太夫 Momochi Sandayū (of 丹波 Tanba), merging into both 甲賀 Kōga and 伊賀流 Iga-ryū. From Momochi’s lineage, it entered the 紀州藩名取流 Kishū-han Natori-ryū (Kishū domain Natori-ryū), and after 信綱 Nobutsuna, it was passed down to the 戸田氏 Tōda-shi (Tōda clan).

戸田流 Tōda-ryū

A manual exists from 黒塚十太夫 Kurotsuka Jūtayū.

頓宮流 Tongū-ryū

Founded by 頓宮四方介之祐 Tongū Shihōsuke no Suke. A lineage of 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū.

永井流 Nagai-ryū

Passed down in 伊勢 Ise.

中川隼人流 Nakagawa Hayato-ryū

Founded by 中川小隼人綜貞 Nakagawa Kohayato Sōtei. Same as 中川流 Nakagawa-ryū.

中川流 Nakagawa-ryū

Founded by 中川小隼人綜貞 Nakagawa Kohayato Sōtei. Sōtei served 津軽倍政 Tsugaru Baisei of 陸奥弘前 Mutsu Hirosaki, acting as the head of the 早道之者 Hayamichi no Mono (scouts) with a stipend of 200 koku. A lineage of 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū. The 早道之者 Hayamichi no Mono also captured 相馬大作 Sōma Daisaku, the mastermind of the 津軽侯暗殺事件 Tsugaru-kō Ansatsu Jiken (Tsugaru Lord Assassination Incident, also known as the 山騒動 Yama Sōdō), in his hideout in Edo.

中山流 Nakayama-ryū (忍 Shinobi)

Associated with the 津軽藩 Tsugaru-han (Tsugaru domain), under 津軽政 Tsugaru Masa’s retainers, with ninjas following the 甲賀伝 Kōga-den (Kōga tradition). The head of the 早道之者 Hayamichi no Mono (scouts) managed 200 members. Founded by 中川小隼人綜貞 Nakagawa Kohayato Sōtei. His original name was 小源太 Kogenta, changed to 小隼人 Kohayato in 天和元年 Tenna 1-nen (1681), and later to 次郎太夫 Jirōtayū in his final years. He passed away in 禄元年 Roku 1-nen (1688). The 早道御役 Hayamichi Goyaku (scout role) was abolished during the 宝暦年間 Hōreki Gannen (1751–1762) but was reinstated a few years later (Ōkufuji Monogatari). The scouts were central to espionage during peasant uprisings and internal conflicts among senior vassals over the lord’s succession. They also searched for the hideout of 相馬大作 Sōma Daisaku, who failed to assassinate the Tsugaru lord, and were referred to as 早道之者 Hayamichi no Mono ninjas dispatched from the domain.

名取流 Natori-ryū

Emerged from 甲州流 Kōshū-ryū. Founded by 甲州先手の士 Kōshū Senkō no Shi (Kōshū vanguard samurai) 名取余市丞正俊 Natori Yoichijō Masatoshi. In 元和五年 Genna 5-nen (1619), he died of illness in 信州 Shinano under the 真田 Sanada clan. The second-generation 三十郎 Sanjūrō studied 楠流軍学 Kusunoki-ryū Gungaku under 楠不伝 Kusunoki Fuden, and further learned various schools under 島田潜斎 Shimada Sensai and others. He revised Yoichijō’s teachings into 真補流 Shinpo-ryū and served the 紀州藩 Kishū-han (Kishū domain).

南木流 Nanki-ryū

A lineage of 楠不伝正辰 Kusunoki Fuden Masatake. In 寛文十二年 Kanbun 12-nen (1672), 木村奥之助久康 Kimura Okunosuke Hisayasu, a retainer of the 尾張徳川家 Owari Tokugawa-ke (Owari Tokugawa family), adopted this name. Hisayasu was originally a 山伏 Yamabushi (mountain ascetic) from 甲賀 Kōga. His younger brother, 木村久種 Kimura Hisatake, served as a leader of 50 men in the 遠江横須賀藩 Tōtōmi Yokosuka-han (Tōtōmi Yokosuka domain).

忍光流 Ninkō-ryū

A lineage of 武田流 Takeda-ryū.

忍甲流 Ninkō-ryū

Same as 忍光流 Ninkō-ryū.

根来電光流 Negoro Denkō-ryū

Founded by 根来電光 Negoro Denkō (of 紀伊 Kii).

根来流 Negoro-ryū

Founded by 杉之坊明算 Suginobō Meisan. His secular name was 津田明算監物 Tsuda Meisan Kanmotsu. Together with his older brother 津田算長監物 Tsuda Sanchō Kanmotsu, they created 根来流忍法 Negoro-ryū Ninpō from traditions passed down through generations. Sanchō introduced firearms (鉄砲 Teppō) from 種子島 Tanegashima, commissioning blacksmiths in front of 根来寺 Negoro-ji (Negoro Temple) to produce them. Since then, Meisan and the monk-soldiers of Negoro-ji possessed a significant number of firearms and excelled in marksmanship.

野間流 Noma-ryū

Founded by 野間半左衛門重直 Noma Hanzaemon Shigenao. A lineage of 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū.

白雲流 Hakun-ryū

Founded by 白雲道士 Hak’un Dōshi during the 養和年間 Yōwa Gannen (1181–1182).

羽黒流 Haguro-ryū

Passed down in 出羽久保田 Dewa Kubota to the 佐家 Sa-ke (Sa family).

波多野流 Hatano-ryū

Passed down in 丹波 Tanba.

服部流 Hattori-ryū

The ninjutsu of the 服部党 Hattori-tō (Hattori faction) within 伊賀流 Iga-ryū.

備前流 Bizen-ryū

Founded by 香取平左衛門 Katori Heizaemon. A branch of 伊賀流 Iga-ryū. Passed down in the 岡山池田家 Okayama Ikeda-ke (Okayama Ikeda family).

福島流 Fukushima-ryū

Founded by 野尻次郎右衛門成正 Nojiri Jirōemon Narimasa. Passed down among the retainers of the 広島藩福島 Hiroshima-han Fukushima (Hiroshima domain Fukushima). Derived from 伊賀流 Iga-ryū. Here, ninjas were reportedly called 外聞 Sotobun.

福智流 Fukuchi-ryū

Founded by 福智有勝 Fukuchi Arukatsu (of 下野宇都宮 Shimotsuke Utsunomiya). His disciple was 木村知氏 Kimura Tomouji during the 享保年間 Kyōhō Gannen (1716–1735).

藤林流 Fujibayashi-ryū

Founded by 藤林長門寺 Fujibayashi Nagatoji (of 伊賀塚田 Iga Tsukada). The ninjutsu of the 藤林党 Fujibayashi-tō (Fujibayashi faction) within 伊賀流 Iga-ryū. Served the 藤堂家 Tōdō-ke (Tōdō family).

扶桑流 Fusō-ryū

Founded by 武内宿解 Takeuchi Sukukai. The revitalizing founder was 藤田麗斎 Fujita Reisai.

不動真徳流 Fudō Shintoku-ryū

A manual exists from the 文政年間 Bunsei Gannen (1818–1830).

北条流 Hōjō-ryū

Said to be founded by 乱波の風魔小太郎 Ranba no Fūma Kotarō. Also called 風魔流 Fūma-ryū due to their elusive, ghost-like nature. This likely stems from the 風魔一党 Fūma Ittō (Fūma clan) being a nomadic group of hunters (猟師マタギ Ryōshi Matagi) and mountain dwellers (山窩 Sanka). Ninja designations were standardized as 草 Kusa, かまり Kamari, 物見 Monomi, 突破 Toppa, and 乱波 Ranba.

北条流無楽派 Hōjō-ryū Muraku-ha

Same as 氏隆流 Ujitaka-ryū and 上泉流 Kamiizumi-ryū (military strategy). The manual 土鑑専要 Dokan Sen’yō exists, which includes ninjutsu techniques.

堀内小隼人流 Horiuchi Kohayato-ryū

Founded by 大津育亮 Ōtsu Ikusuke.

松田流 Matsuda-ryū

Founded by 松田金七郎秀人 Matsuda Kinshirō Hideto, a man from 大和 Yamato, and a disciple of 小幡勘兵衛 Obata Kanbei. He first served 前田利家 Maeda Toshiie, then 浅野光晟 Asano Mitsutake of 安芸広島 Aki Hiroshima. Passed down in the 水戸徳川家 Mito Tokugawa-ke (Mito Tokugawa family).

松元流 Matsumoto-ryū

Passed down in 下野 Shimotsuke.

美濃流 Mino-ryū

During the era of 斎藤道三 Saitō Dōsan, ninjutsu was practiced by the 黒川党 Kurokawa-tō (one of the 甲賀五十三家 Kōga Gojūsan-ke, Kōga 53 Families) and 美濃透破 Mino Suppa’s 稲田九郎兵衛 Inada Kurōbei.

名映流 Meiei-ryū

Passed down in 紀伊 Kii.

無極量情流 Mukiryōjō-ryū

Passed down in 駿府 Sunpu during the 万治年間 Manji Gannen (1658–1661). Founded by 浅見忠勝千葉河内 Asami Tadakatsu Chiba Kōchi.

百地流 Momochi-ryū

Founded by 百地三太夫泰光 Momochi Sandayū Taikō, an 上忍 Jōnin (high-ranking ninja) of 伊賀流 Iga-ryū. The lineage is recorded as: 百地泰光 Momochi Taikō → 百地泰久 Momochi Taihisa → 百地泰遠 Momochi Taien → 百地保好 Momochi Yasutake → 百地保理 Momochi Yasutake → 百地保重 Momochi Yasushige.

森川理極流 Morikawa Rigoku-ryū (理極流 Rigoku-ryū)

A branch of 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū.

森流 Mori-ryū

The ninjutsu of the 森組 Mori-gumi, covert agents of the 江戸幕府 Edo Bakufu (Edo Shogunate).

山形流 Yamagata-ryū

Founded by 山形将監 Yamagata Shōkan, a man from 尾州 Bishū, in 寛永十二年 Kan’ei 12-nen (1635). Passed down in the 仙台伊達家 Sendai Date-ke (Sendai Date family).

大和忍法 Yamato Ninpō

Founded by 矢野剛秀 Yano Takeshide.

山中流 Yamanaka-ryū

Founded by 山中山城守長俊 Yamanaka Yamashiro-no-Kami Nagatoshi, a man from 甲賀 Kōga. He initially served 六角義賢 Rokaku Yoshikane, then 織田倍長 Oda Baichō, and was favored by 豊臣秀吉 Toyotomi Hideyoshi, leading him to join the Western Army at the 関ヶ原の合戦 Sekigahara no Gassen (Battle of Sekigahara). However, he later served the 徳川氏 Tokugawa-shi (Tokugawa clan). Two volumes of a 術書 Jutsusho (technique manual) have been preserved.

義経流 Yoshitsune-ryū

Said to be founded by 源九郎義経 Gen Kurō Yoshitsune. He trained in 修験道 Shugendō at 鞍馬山 Kurama-yama, excelling particularly in jumping techniques (跳躍術 Chōyakujutsu), with 伊勢義盛 Ise Yoshimori’s 伊賀流忍法 Iga-ryū Ninpō incorporated. Passed down through generations in the 福井藩 Fukui-han (Fukui domain). Ninja designations were 隠忍術 Inninjutsu and 志能便 Shinōben.

理極流 Rigoku-ryū

Same as 森川理極流 Morikawa Rigoku-ryū. A branch of 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū.

黄門流 Kōmon-ryū

A branch of 白雲流 Hakun-ryū.

和田流 Wada-ryū

Founded by 和田伊賀守惟政 Wada Igamori Tadamasa. A lineage of 甲賀流 Kōga-ryū. Refers to the 甲賀流和田派 Kōga-ryū Wada-ha (Kōga-ryū Wada faction).

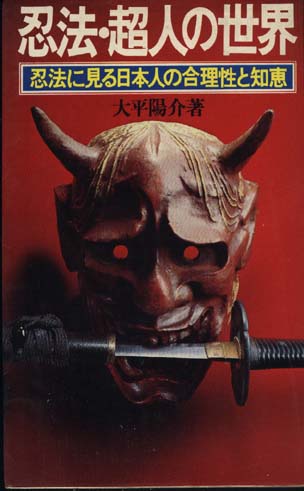

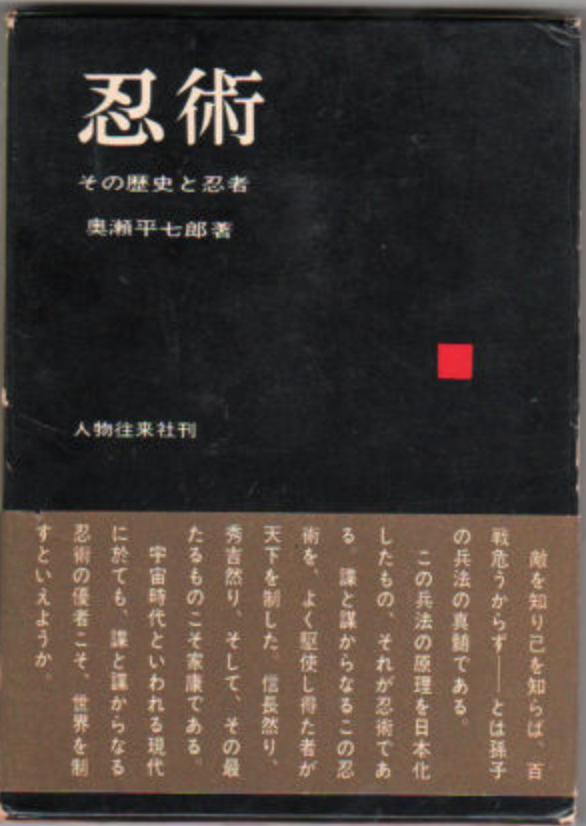

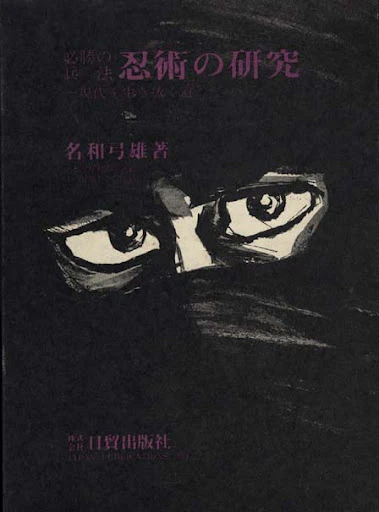

Bessho History Reading Book No. 72 – Data file of 132 Ninjas.

I could not find much information about this book, who wrote it or the publisher. It looks like it was published as a history book/magazine published monthly.

Being the 72’nd book I guess it has been around for many years, the web site jinbutsu.co.jp is dead so I don’t know much about the publisher.

Published May 2001

228 pages

ISBN-10 : 4404027729

ISBN-13 : 978-4404027726

The post History of Ninjutsu: List of Ninjutsu Schools appeared first on 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu.…