忍術千一夜 NINJUTSU SENICHIYA (The Art of Ninja in 1001 Nights)

From 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu by Toryu

I was translating another Hiden Magazine article for Bujinkan.online and came up on the following segment about Hatsumi Sōkes experience about his 1964 TV appearance om 忍術千一夜 NINJUTSU SENICHIYA (The Art of Ninja in 1001 Nights).

NINJUTSU SENICHIYA was a segment to the Toei Animation TV anime 少年忍者風のフジ丸 “Shōnen Ninja Kaze no Fujimaru” (Fujimaru of the Wind: The Childhood of a Ninja) aired from June 7, 1964, to August 31, 1965.

Hatsumi Sōke showcased and explained various aspects of Ninjutsu and ninja tools, particularly from the Togakure-ryū school. The segment was presented to actress 本間千代子 Honma Chiyoko.

From July issue of Hiden Magazine published in 2002…

Renewing the Image of the Ninja

The Enigmatic World of Ninjas: Reimagined

Once, ninjas were enigmatic figures in storytelling and the Tachikawa Bunko, where they performed mystifying feats like disappearing in a puff of smoke or transforming into gigantic frogs or monsters. This fairytale-like image of ninja techniques, where they would bite scrolls, form seals, and chant spells, dominated the public consciousness.

In early ninja movies, this image prevailed. Films like “Kage no Eijimaru” starring a young Hiroshi Matsukata and Toei Animation’s “Shonen Sarutobi Sasuke” exemplified this. However, Masaaki Hatsumi Sōke actively participated in visual media like TV and movies, introducing the true nature of Ninjutsu to the public, transforming the existing image of ninjas.

A turning point was the movie “Shinobi no Mono” directed by Satsuo Yamamoto. Here, Hatsumi Sōke, along with the then-living Takamatsu Sōke, provided Ninjutsu guidance, creating a realistic ninja portrayal on screen. Techniques from the Togakure-ryu could be seen throughout the movie, including rust-plate and stick techniques, body movements, and ninja walking.

Additionally, in Toei Animation’s TV anime “Shonen Ninja Kaze no Fujimaru,” a segment called “Ninpo Sen’ichiya” was included, where Hatsumi Sōke explained and demonstrated Ninjutsu and ninja tools. This unprecedented project likely introduced Togakure-ryu and Hatsumi Sōke to many.

“It was only a 3-minute segment, but the shooting took about an hour and a half. The studio lights were so hot back then that the studio flowers would wilt in about 20 minutes, so we had to replace them several times during shooting. The Ninjutsu demonstration took about 7 hours,” Hatsumi Sōke recalls.

Hatsumi Sōke continued to provide guidance in several movies, TV shows, and stage performances. Notable works include Teruo Ishii’s “Direct Hit! Hell Fist,” Lewis Gilbert’s “You Only Live Twice,” and Kado Hanado’s “Sengoku Mayou Monogatari.” He also appeared in numerous programs, contributing to the creation of a realistic ninja image and establishing Ninjutsu as a martial art. However, the sensationalist public perception of Ninjutsu and ninjas has always been a significant barrier for Hatsumi Sōke, likely posing challenges to this day.

忍術千一夜 NINJUTSU SENICHIYA 19 Episodes

NINJUTSU SENICHIYA EPISODE LIST:

01. SENBAN-SHURIKEN

02. BŌ-SHURIKEN

03. TENMON, KETSU-IN MAKIMONO

04. NINJA SHOZOKU, NINJATŌ

05. SHINOBI BUKI

06. TETSUBUSHI, METSUBUSHI, KASUNAI

07. GETA, ARUKI

08. SUITON NO JUTSU

09. KATON NO JUTSU, KAYAKUJUTSU

10. KOPPŌJUTSU

11. NINJATŌ, KENPŌ

12. KAYAKUJUTSU, TEPPŌJUTSU, HŌJUTSU

13. KAMAYARI

14. CHITON, SUITON NO JUTSU

15. BŌJUTSU

16. TOGAKURE-RYŪ BIKENJUTSU, YOROI

17. SHIKOMI, HENSOJUTSU

18. KUSARIGAMA, KYŌKETSUSHOGE

19. TOBIDOGU, SHURIKEN, FUKIYA

The post 忍術千一夜 NINJUTSU SENICHIYA (The Art of Ninja in 1001 Nights) appeared first on 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu.…

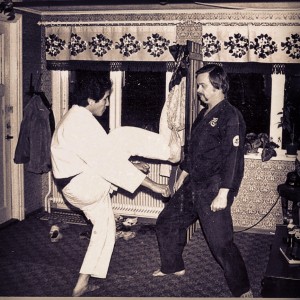

Bo Munthe was the pioneer who brought Bujinkan to Sweden and Europe in. In 1975 Ischizuka Sensei came over for two weeks and introduced Bo to Bujinkan Budo Taijutsu (then simply Ninjutsu), shortly after he went over to Japan and met Hatsumi Soke for the first time. If it wasn’t for him, who knows when someone else would have brought the art to Europe. He recently had his 70’th birthday. Hooray!

Bo Munthe was the pioneer who brought Bujinkan to Sweden and Europe in. In 1975 Ischizuka Sensei came over for two weeks and introduced Bo to Bujinkan Budo Taijutsu (then simply Ninjutsu), shortly after he went over to Japan and met Hatsumi Soke for the first time. If it wasn’t for him, who knows when someone else would have brought the art to Europe. He recently had his 70’th birthday. Hooray!