From 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu by admin

Introduction to the Four Worlds of Mastery

The Four Worlds of Mastery

In the disciplined and deeply philosophical world of Bujinkan, the journey from novice to master involves more than physical prowess. Additionally, it encompasses profound personal growth. The “Four Worlds of Mastery” guide this path, mirroring the traditional martial arts progression of Shu-Ha-Ri. It also highlights common cognitive biases, such as the Dunning-Kruger effect. Understanding these stages offers practitioners a roadmap for development that extends beyond physical skills to encompass mental and spiritual maturation.

Incompetent Awareness

“Incompetent awareness” marks the initial stage in a martial artist’s journey. Here, you recognize your novice status and embrace the humility that comes with starting anew. Like the Shu phase in Shu-Ha-Ri, this stage is about strict adherence to form and technique, absorbing knowledge like a sponge. You learn to perform kata (forms) and techniques exactly as taught, respecting the wisdom and effectiveness of established methods. This phase is foundational, as it builds the discipline and basic skills necessary for advanced exploration.

Incompetent Unawareness

As skills and confidence grow, practitioners often enter the stage of “incompetent unawareness,” where the Dunning-Kruger effect becomes most apparent. Here, you might feel more competent than you actually are due to initial successes and basic fluency in techniques. This stage is a critical juncture and reflects the early transition from Shu to Ha, where the danger lies in becoming complacent with one’s perceived level of skill.

You must remain vigilant to continue pushing boundaries and seeking deeper understanding instead of settling for superficial knowledge. This stage urges practitioners to recognize the breadth of what they don’t know and to approach training with a critical eye.

Competent Awareness

Transitioning into “competent awareness,” practitioners begin to deeply integrate their skills and knowledge. This stage aligns with the Ha phase of Shu-Ha-Ri, characterized by experimentation and adaptation. You understand the principles behind each technique and start to experiment with variations, adapting what you’ve learned to suit different situations and personal style.

This is a period of reflection and critical thinking, where you assess your abilities realistically and work on refining your techniques. Here, the practitioner is skilled and knowledgeable yet remains acutely aware of the limitations and gaps in their expertise.

Competent and Unaware

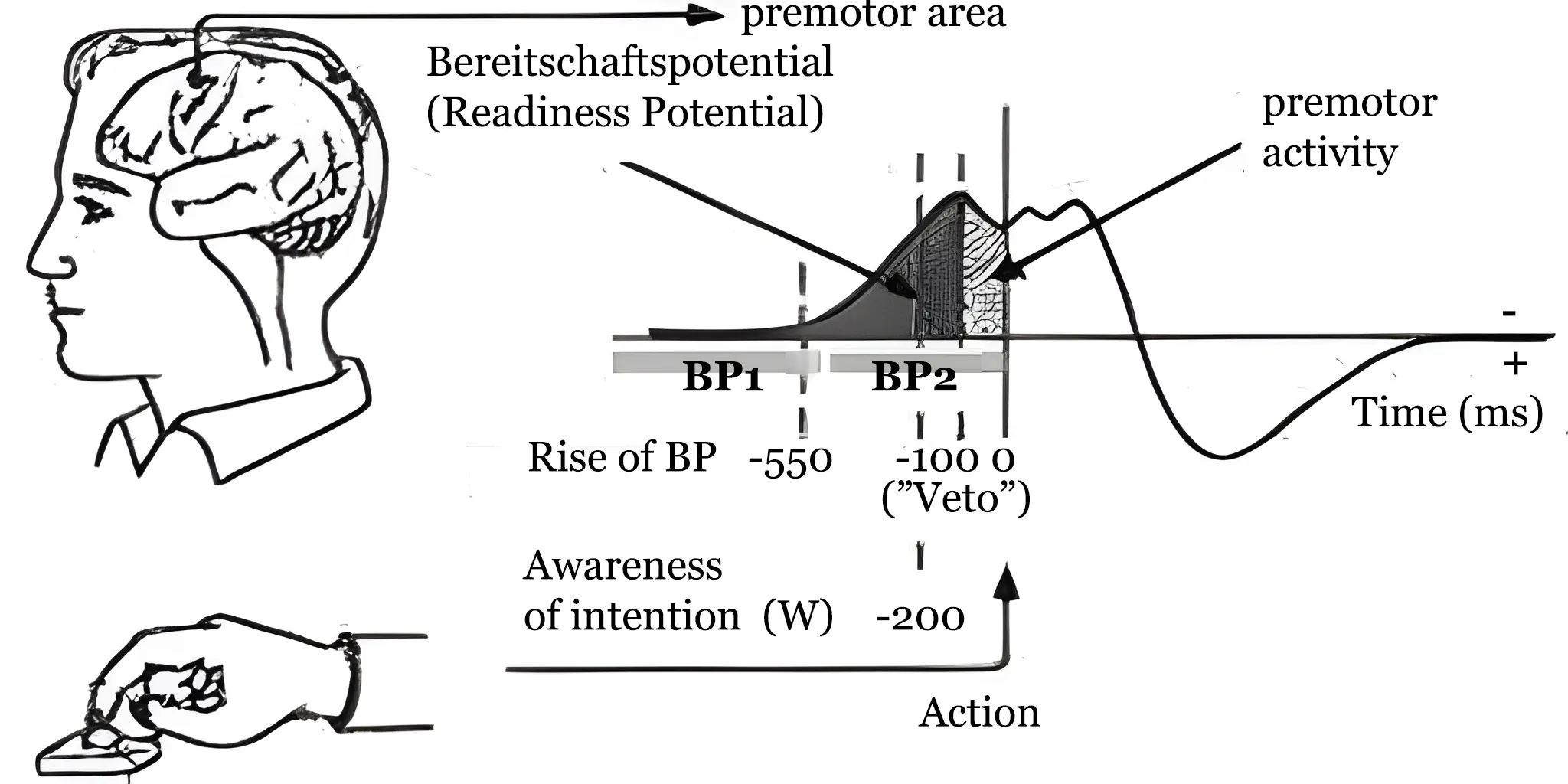

The final stage, “competent and unaware,” is where true mastery begins to shine. This stage mirrors the Ri phase, where practitioners execute techniques with natural ease and deep-rooted skill, making them appear instinctual.

At this level, the mind no longer consciously dictates actions; the body responds to threats and opportunities with a fluidity and grace that seem almost preternatural. This is the stage where practice transcends physical action and becomes a form of moving meditation, embodying the essence of Bujinkan in every motion.

Overwhelming Spirit

In Shinden Shura Roppō Takamatsu Sensei wrote about this experience.

| There’s an interesting story related to this. When I was at Toda Shinryuken Sensei’s dojo, a martial artist from the 関口流 Sekiguchi-ryu came for a challenge match. At that time, it was customary for younger, skilled practitioners to sit at the lower end, while older, less capable ones took the higher seats. Among us was a man, around 37 or 38, with an imposing physique but a scarred face, possibly from burns, which made him look fearsome. However, his skill was limited, and he loved to compete despite often losing. That day, he boldly took the highest seat, and when the match began, he insisted on going first. Everyone tried to dissuade him, knowing he would lose, but he wouldn’t listen. So, he went out, exchanged formalities with the opponent, and as they bowed and separated, he suddenly widened his scarred eyes, contorted his face into a terrifying expression, and with a thunderous shout and stomp, he startled the Sekiguchi-ryu opponent. The opponent, terrified, jumped back and conceded the match. When Toda Sensei asked the Sekiguchi-ryu practitioner why he gave up, he confessed that he was scared and thought he would be facing a weaker opponent from the lower seats. This instance shows how a mental defeat can occur even before the physical match. In martial arts, one must maintain a constant, unshaken spirit, not startled or intimidated by external changes. The true value of martial arts lies in cultivating this unflinching spirit. |

In what category would you place the student of Toda Sensei? Where would you put the Sekiguchi student? I think it is an interesting story that teach us that sometimes courage is better than skills.

Integrating Shu-Ha-Ri and Dunning-Kruger into Bujinkan Training

Integrating the understanding of Shu-Ha-Ri, traditionally viewed as a 30-year progression, along with the awareness of cognitive biases like the Dunning-Kruger effect, is crucial for holistic development in Bujinkan training.

Recognizing your current position within these stages is essential for maintaining a realistic assessment of your skills and encouraging ongoing improvement. Furthermore, the Dunning-Kruger effect serves as a vital reminder to stay humble and vigilant. It urges you to continuously question your level of skill and actively seek feedback from more experienced practitioners.

Practical Applications and Training Advice

To navigate these stages effectively, consider the following practical steps:

- Seek Continuous Feedback: Regularly seek out feedback from instructors and peers to gain an accurate understanding of your skill level.

- Engage in Deliberate Practice: Focus on areas of weakness and continuously challenge yourself with new learning opportunities.

- Reflect and Journal: Maintain a training journal to reflect on lessons learned, challenges faced, and progress made.

- Teach Others: Teaching is a powerful tool for deepening understanding and identifying gaps in one’s own knowledge.

- Stay Open to Learning: Cultivate the mind of a three-year-old, an age marked by peak curiosity and learning. Embrace this beginner’s mindset at every stage of your expertise to continuously discover new insights and techniques.

Conclusion

Navigating the “Four Worlds of Mastery” in Bujinkan calls for a balanced mix of rigorous practice, self-assessment, and personal growth. By moving through each stage—from eager learner to master practitioner—you partake in both the physical and transformative aspects of martial arts. This process molds both mind and spirit. The journey reflects Shu-Ha-Ri’s lasting principles and provides a challenging path to mastery. Recognizing these stages and the pitfalls of the Dunning-Kruger effect equips you with essential tools for true mastery in Bujinkan.

Footnotes:

- Shu (守): Shu means to protect or obey. It emphasizes the importance of learning foundational techniques exactly as taught, without deviation.

- Ha (破): Ha means to break. In martial arts, this stage is about breaking away from traditions to explore and adapt techniques personally.

- Ri (離): Ri means to separate or transcend. It signifies achieving a level of skill so advanced that techniques are executed instinctively and effortlessly.

- Dunning-Kruger Effect: A cognitive bias wherein individuals with low ability at a task overestimate their ability, while those with high ability underestimate theirs, often due to a lack of self-awareness.

The post 四習界 Shishūkai: Four Worlds of Mastery appeared first on 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu.…

Read More