Kūkan (空関): The Empty Gate

From Bujinkan – The Magick & The Mundane by Shawn Gray

When I was asked for a theme for three upcoming Bujinkan seminars (details below) that I’ve been invited to give in April, the concept of Kūkan immediately came to mind. Kūkan is a term that gets thrown around a lot in the Bujinkan, and Chris Taylor, host of the Vancouver seminar, asked me to elaborate more specifically on how we’ll be approaching it…

When Hatsumi Sōke uses the word Kūkan in the Dōjō, it’s most often simply translated into English as “space”, but as is often the case when Sōke speaks, there is frequently a deeper sense than can be conveyed in a single word, and the translator is often pressed to succinctly express the full meaning of one idea as Sōke quickly moves on to the next. For instance, there’s another word that Sōke uses from time to time that’s also translated as “space”: Kokū. In both Kūkan and Kokū, the same character for Kū ( 空 ) is used, which has the meaning of emptiness or void. When this character is pronounced Sora, it means “sky”. It can also be pronounced Kara, as in Karate ( 空手 – “empty hand” ).

But while both Kūkan and Kokū are often simply translated in the Dōjō as “space”, they have quite different meanings. Kokū refers to boundless, limitless space, space that has no borders or boundaries. This term thus often refers to the heavens, the cosmos – outer space. Kūkan, on the other hand, could in one sense be rendered as inner space – it refers to space that has borders or boundaries by which it is outlined or enclosed and by which the shape, dimensions / size, or range (distance) of the space are defined. The character normally used for the Kan of Kūkan is 間, which depicts a sun ( 日 ) in the space between the two doors of a gate ( 門 ). The doors define the space or interval that the sun’s light shines through. This character for Kan can also be pronounced Ma, and it is used in this form in another term often used in the Dōjō – the term Ma-ai ( 間合 ), meaning “distance”, the interval between two points.

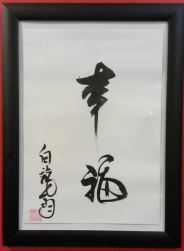

In thinking about the theme for the upcoming seminars, however, I decided to play with the characters a bit. Instead of the Kan normally used in Kūkan, I thought of another Kan – the character used in the word for “joint”, Kansetsu ( 関節 ). This came to mind because the skeletal joints are an example of Kūkan within the body structure. The little spaces between our finger joints, for example, are what enable us to use our hands with a dexterity that wouldn’t be possible if our fingers were each formed from a single, solid bone. (Similarly, the links in a chain employ empty space for flexibility – and even a rope derives its suppleness  from the small spaces between the strands of which it is composed.) This Kan ( 関 ) is used to convey connection and relatedness. Budō ni kan-suru ( 武道に関する ) means “related to Budō”, for example. So Kūkan written as 空関 has the sense of “related to empty space”.

from the small spaces between the strands of which it is composed.) This Kan ( 関 ) is used to convey connection and relatedness. Budō ni kan-suru ( 武道に関する ) means “related to Budō”, for example. So Kūkan written as 空関 has the sense of “related to empty space”.

Additionally, the character 関 literally means “barrier” or “gate” (a gate being a wall or barrier with an opening in it). Thus, Kūkan written as 空関 also has the sense of being “void of impediment or obstacle” in addition to the sense of relation to empty space, and it’s this idea that I’d like to get across in the Taijutsu techniques that we’ll be working on in the upcoming seminars. Creating space allows one to pass through obstacles without impediment, resulting in smooth, effortless, and efficient movement in the same way that one passes through the empty space in a wall created by a door or gate. An opening is an opportunity that may look like nothing – and it is! That’s what makes it useful. I sum up this paradox with the phrase Nai ga aru ( 無いが有る ), meaning Nothing (or more accurately, nothingness) exists. The theme of these seminars thus refers to finding and creating empty spaces, and using those openings to one’s advantage in Taijutsu. I look forward to seeing many of you in Stockholm, Brussels, and Vancouver!

Kūkan Ikkan!

Shawn Gray

Ryūun (龍雲)

~ Upcoming Seminars (2016) ~

“Kūkan: Nai Ga Aru”

Apr 16-17 – Stockholm (details)

Contact: Kent Thorén (email)

Apr 23-24 – Brussels (details)

Contact: Jan Ramboer (Facebook)

Apr 30 – Vancouver

Contact: Chris Taylor (Facebook)