From The Magick & The Mundane » Bujinkan by Shawn Gray

Finally, some free time to blog again!

In the last blog article I wrote on my early adventures in Japan, I related how I went to Iga in search of Hatsumi Sensei in October 1990, but didn’t manage to find him.

After not having found him, there was nothing else to do but return to Hiroshima and continue with my English teaching schedule. I also went back to my Karate studies, and continued pounding my fists into bloody hamburger against trees.

Back to Eikaiwa!

Back to Blood!

In December 1990, I had the opportunity to travel to the Chito Ryu Karate Hombu Dojo, located in Kumamoto, on the southern island of Kyushu. The Dojo was equipped with two bunkbeds, accompanying four people. When I arrived, there were two guys visiting from British Columbia, Canada, also staying there for training. (I wish I could remember their names after all this time, so that I could track them down. It would be fun to share stories again.) The Soke (Grandmaster) was 40 years old at the time. His father, the founder, had died in 1984. (From what I’d heard, an elder brother had been destined to continue the leadership of the style, but from what I heard, had been disabled in a car accident and therefore unable to continue with training. The younger son, next in line, had been in Tokyo pursuing medical studies, but was recalled to Kumamoto by his father to take over leadership of the lineage.) I stayed at the Dojo for two weeks, and greatly enjoyed the training. I was awed by the skill level of Chitose Sensei and his senior instructors. In the backyard behind the Dojo were two Makiwara punching posts. Wooden covers protected them from the rain, and on the covers were painted a Japanese character which is very familiar to my fellow Bujinkan practitioners. The character is pronounced “Nin“, and is the first character of the word “Ninja.” What was this character doing displayed so prominently at a Karate Dojo? Although sometimes understood in ninjaphile circles to mean “stealth,” the character is more widely used in more mainstream Japanese to mean “restraint,” “patience,” or “perseverance.” It was with these noble ideals in mind that we forged our minds and bodies in the daily training at Hombu Dojo. Kata, Kumite, and Makiwara training were all part of this. By perseverance and austerity in training the body and mind in the way of the Bushido ideal of the Samurai of old, we pushed our mental and physical limits beyond what we thought possible.

Makiwara with “Nin”

Aside from the training itself, there are a couple of memorable experiences from that time in Kumamoto. One was when Chitose Soke took the other visiting Canadians and myself out for a visit to Kumamoto Castle, one of the three premier castles in Japan. Scars from the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 (when Samurai warriors of Satsuma province rebelled against the imperial forces of the Meiji government) pock-marked the stone walls. It was an impressive edifice. Soke took us out for sushi afterwards.

Another memory was from one night when my two new Canadian friends took me out for a night on the town, Kumamoto style. I had never been out drinking in Canada before, let alone in Japan. I had no idea what kind of town I was in or where we were going. Before I knew it, we were sitting at a table ordering drinks, surrounded by very nicely-dressed ladies from the Philippines. I was from a farming town of 3,600 people on the Atlantic Coast of Canada. It took me a while to catch on that these ladies worked here. Anyway, we kept ordering and my two Canadian friends were on my left, engaging the ladies in deep conversation. Almost as if they’d met before. I felt a nudge on my right and turned to see what appeared to be two of the local Japanese bikers. They seemed friendly enough. The one next to me, I discovered through our broken conversation (my Japanese vocabulary was probably about 30 words at this point), did well in the local boxing scene. At least that’s what he told me, as he kept grinning and pointing to the biceps bulging out from under his cut-off denim vest.

I was starting to feel a little bit uncomfortable, but couldn’t really understand why. I started to think I should ask my friends when we were planning to leave. I turned to my left to ask my friend when we were going to get the check, and then felt a fist slam lightly into the right side of my face. My friend turned. “What?” “I think maybe we should go. This guy just hit me.” “Wait a second.” He turned to confer with the other friend. I turned to my right and smiled nervously at the two grinning Japanese guys wearing black leather. They looked like they were having fun. A moment later I turned to the friend on my left again. “What.” Again a punch from the right hit the side of my face. Harder this time. “Look man, our friend on my right here has now hit me in the face twice. We need to go, now.” “Ok.” My two friends stand up. Both of them were about fix-foot two. Sturdy Canadian farming boys. I turned to my right. The two Japanese dudes were gone.

We paid the bill and headed down the elevator. It came to a stop at ground level, and as we stepped out into the parking lot and the doors closed behind us, we found ourselves on the back side of a slowly-shrinking circle, on the perimeter of which were four or five tough-looking locals. The friend on my right made a quick beeline to the right, down an alley. I was close behind him. Closer than I normally am to other guys. We zig-zagged quickly through some alleys and eventually found ourselves with our hands on our knees, panting and out of breath, outside the Hombu Dojo “bunk room.” There were just two of us. The other Canadian friend was nowhere in sight. It was around 2am. We waited. We didn’t want to wake anyone and cause a scene. We waited some more.

After what seemed like at least 20 minutes, our friend loped quietly out of a side street and over to join us in the shadow of the Dojo roof. “Where were you?” “What took you so long?” “What happened!?” He told us that he didn’t see us bolt away right away, and before he knew it, he’d been surrounded. As the four or five tough guys closed in, one of them had pulled a knife. Our friend had a quick eye and saw the guy start to draw. He jumped on him and punched him to the ground, and then made a run for it. It took him a while to give them the slip and sneak back to join us at the Dojo without being found. We quietly slid into the Dojo dorm and into our bunks, glad to be alive. The next morning Soke asked us how our night had been. We played it cool and made like nothing out of the ordinary had happened. He smiled.

The next day was the day he took us to Kumamoto Castle. On the way in the car he told us that he’d heard about what happened, saying he was glad we got through it ok, and apologized “for those with bad manners.”

Chitose Soke and 2 Canucks

Before I left Kumamoto to go back to Hiroshima for the New Year, 1991, Chitose Soke gave me some training advice for when I got back. Study also Kendo, for speed and timing, and also Judo, for throws and locks. I was a bit surprised to hear this. Martial arts masters aren’t always known for recommending that their students study other arts. Soke’s openness in this way really impressed me.

When I got back to Hiroshima, I asked around about Kendo training. There was a small Okonomiyaki bar in Hiroshima run by a young Japanese woman and her American (Seattle, I think it was) husband. He was very into Kendo, and was proud of doing it in Japan as a foreigner. He had photos of his shop and would brag about being a 3rd Dan, which I think he said was one of the highest ranks of any foreigner in Western Japan at the time. I have no real way of knowing whether that was true or not, but that’s what he’d say. He agreed to bring me along to his Kendo class and introduce me to his teacher, Fujiwara Sensei.

With Fujiwara Sensei

Lesson with Fujiwara Sensei

Fujiwara Sensei was a wonderful old (to a twenty-year old!) Japanese man who always had a huge smile floating across his face. He had a very soft, gentle manner and a kind way of speaking. For some reason he took a real liking to me and, in addition to selling me $1,300 of training gear for $300 and giving me a set of Hakama with both of our names embroidered in it, also refused to let me pay for lessons. This irritated the American guy who introduced me. Fujiwara Sensei had been his teacher for years, but he always had to pay for his lessons. I was unable to explain why Sensei seemed to like me so much. Maybe it was just because I was always so polite. I’d always greet him with the extra-polite, “O-kawari arimasen ka?” (“Has there been no change [in your health, etc.]?”) He’d always smile widely and say, “Hai, arimasen!” (“Yes, there hasn’t!”) My American friend was less than impressed. He’d pound the hell out of me when we were paired up in the Dojo and I would go home with headaches from getting hit on the head so hard repeatedly. I didn’t know what to do. I could not force Sensei to take the money. Out of desperation I would bring bags of fruit to the Dojo and force them on him. The Japanese students would laugh at this, but I didn’t know what else to do. I was never ranked in Kendo, although in addition to the regular Suburi and Randori training, Fujiwara Sensei also taught me 5 Bokuto Kata forms and 2 Shoto Kata forms. I seem to remember that these were for Shodan level, but my memory could be wrong on that.

Kenjutsu Lesson

As far as Karate ranking went, I went to Japan as a brown-belt. Kanao Sensei in Fukuyama wanted to promote me, but said that Chito Ryu had prohibited ranking of foreigners to Yudan grades (black belt grades) in Japan. Apparently some Japan-promoted foreigners had in the past gone back to their home countries and caused political problems by claiming their rank from Japan was worth more than a locally-given rank of the same degree. So I wasn’t promoted during my stay in Japan, but Kanao Sensei did teach me some very interesting Kata that made things interesting when I got back to Canada.

To be continued…

…

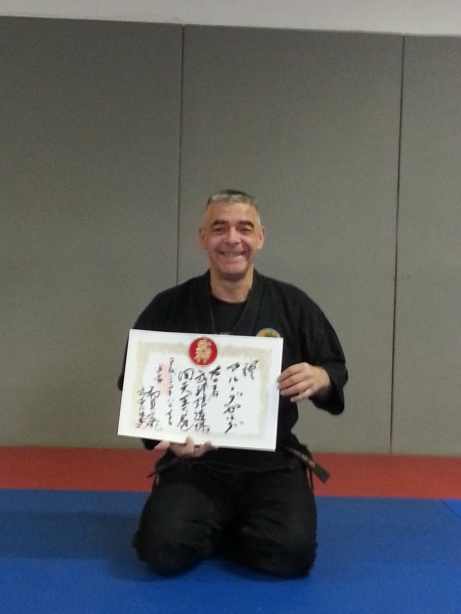

Recently Hatsumi Sensei honored me by awarding me with a diploma of Shi Tennô.

Recently Hatsumi Sensei honored me by awarding me with a diploma of Shi Tennô.

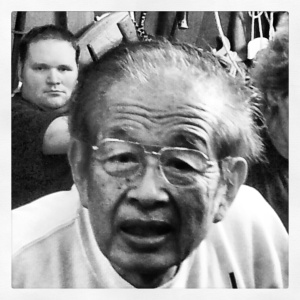

The second day of the dkms was intense with Sensei insisting on very small technical points. This year the theme was kaname (essential points), and the kaname is to be found in many details.

The second day of the dkms was intense with Sensei insisting on very small technical points. This year the theme was kaname (essential points), and the kaname is to be found in many details.

Friday was the beginning of the dkms. The day began well as Sayaka Oguri joined us in Kashiwa on the train going to Shimizu Koen.

Friday was the beginning of the dkms. The day began well as Sayaka Oguri joined us in Kashiwa on the train going to Shimizu Koen. Last week Hatsumi sensei said that we must know fight like gentlemen using no strength but only adapting our body to uke’s attacks but with some kind of high class touch. We do not want to fight but we do not want to hurt either.

Last week Hatsumi sensei said that we must know fight like gentlemen using no strength but only adapting our body to uke’s attacks but with some kind of high class touch. We do not want to fight but we do not want to hurt either.