Manga, Hokusai, Hatsumi

From Shiro Kuma's Blog by kumablog

When I was young, I spent my free time drawing Chinese ink sketches and listening to classical music (when I was not training on the mats).

I loved, and still love, black and white drawings without colors. And one of my dreams was to get a copy of “Manga”, the famous books of drawings by Hokusai, the Japanese woodblock printer. But these books were not published at a price I could afford at that time. They are now available at amazon.com (1). Albrecht Durer (2) and Hokusai (3) were my favorites.

Hokusai lived in the 18th and 19th century (1760 – 1849) so he died nearly 20 years before Meiji. These books are a testimony of pre-Meiji Japan and depict the life of the people at that time.

Hokusai created the “Manga” in 1811 at age 51, half a century before Meiji (4). And as far as I know, he realized these drawing to teach his students how to draw like him. Remember that these drawings were sculpted on woodblocks by an army of apprentices.

This first manga is a collection of thousands of drawings depicting the daily life of the Japanese people.

In Japanese 漫画 “manga” means drawing (cartoon picture) but I prefer to see it as 万画 “manga” (10000 sketches or images).

This is the origin of the word “manga” used by millions of teenagers and young adults today. The funny thing is that the majority do not know where this word is coming from.

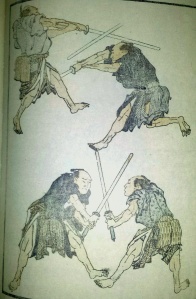

So when I received the two volumes last week, I began to look into them and search for budo related drawings. The image on this blog is the reason why I decided to write this article. Let’s do some archeological history on sword fighting.

On the page, you see two pairs of fighters. The upper ones (5) and the lower ones have their hands regrouped like you would in modern iaidō. Which is typical from peace time period and switch from Tachi to katana. I don’t think Hokusai knew a lot about warfare, but he drew what he was watching. So we should consider this like a photography.

This brings one observation: 50 years before Meiji, the system of holding the Tsuka with hands out together was already in use. One of my former sword teacher told me that the close grip was developed during peace time when there were no Yoroi anymore. This grip was faster and more precise than the regular Tachi grip with hands apart.

Another remarkable point is that both groups of fighters have their legs in Gyaku unlike what was the habit with Yoroi fighting. This is also what is taught today in iaidô and often in battodô (right hand and left foot forward). With a Yoroi this is nearly impossible as you have to use the weight of the Yoroi in the hitting process. But in Keikogi and katana, the distance being smaller it makes sense.

This beautiful drawing by Hokusai is not what is taught in the Bujinkan where we are dealing more with the Kamakura and Muromachi type of fighting. But it depicts exactly the ways of the sword during the Edo period.

Hatsumi sensei is like Hokusai, he copies natural movement because everything is about moving according to the situation. There is no dogma, as long as it works.

Hatsumi sensei is like Hokusai drawing these 10000 sketches, his books and videos are like a modern manga that he gave us to be inspired and find natural movement.

Natural movement exists by itself, it appears without thinking. Like Hokusai, we simply have to watch it unfold in front of our eyes.

Hokusai and Hatsumi sensei are painters, they do not teach techniques, they show that life is like that, something natural that you see. This is the true meaning of “Shikin Haramitsu Daikomyō”.

“Life is like that” or 活然 is pronounced “Katsushika”, and it is Hokusai first name.

_____________________________________________________

1. Manga also exist in other languages.

2. About Albrecht Durer

3. About Hokusai life

4. About Kokusai Manga

5. the two fighters are in a wrong position on the page. The sword of the black fighter is the same one crossing the sword of the left fighter. They are positioned like that in the book even though he should be above the left fighter.