Tsunagaru: Stay Connected!

From Shiro Kuma by kumablog

A week ago, my last class with Sensei for this trip was another great one, with many insights to bring and to train at home.

A week ago, my last class with Sensei for this trip was another great one, with many insights to bring and to train at home.

Before we began, Hatsumi Sensei spoke about the new statue of Kannon that he acquired recently. More than a statue, it is a symbol. When Takamatsu Sensei stayed one year on the mountain, he trained under the guidance of a hermit. During this time he developed a strong connection with the goddess Kannon. He saw Kannon as the end of his mountain shugyō and a witness of the Musha Shugyō accomplished in the wilderness.

When Hatsumi Sensei saw this statue at his regular antique shop, he took it as a reminder of Takamatsu sensei’s story. For him, this statue placed at the centre of the Shinden symbolises the fact that we (he) have reached the level of Takamatsu sensei’s understanding.

When Hatsumi Sensei saw this statue at his regular antique shop, he took it as a reminder of Takamatsu sensei’s story. For him, this statue placed at the centre of the Shinden symbolises the fact that we (he) have reached the level of Takamatsu sensei’s understanding.

The Goddess Kannon connects us (him) to the late Takamatsu Sensei.

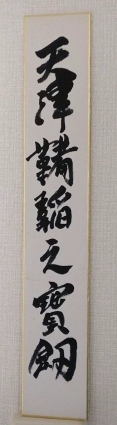

Before we did the salute, Sensei facing the Shinden called me to give me a Ōmamori from the Amatsu Tatara. It reads “Amatsu Tatara no Hōken”. Hōken is the treasure sword that protects from sickness and evil. That was a kind attention.

Before we did the salute, Sensei facing the Shinden called me to give me a Ōmamori from the Amatsu Tatara. It reads “Amatsu Tatara no Hōken”. Hōken is the treasure sword that protects from sickness and evil. That was a kind attention.

Kannon, the Amatsu Tatara no Hōken, these are connecting us to our Life. And this is the same type of connection that we’re looking for in the encounter.

During class, Sensei spoke many times about the importance of Tsunagaru. (1) We have to connect to the moment, to the opponent, and to the fight. Mutō Dori deals with this quality of the connection.

At any given moment we have to be protected, in “security”. Sensei repeated that in the exchange we had to safe and secure: “Anzen”. (2) We can be Anzen because we do not fight, we play (Asobi – 3) with Uke, using our fingers, our understanding of distance, and our unwillingness to do anything to defeat him. “Master the Kokû” he added, “and never give the opponent anything he is expecting. We have to keep changing (moving) because life is about changing permanently. If you stop moving your body and your mind, you cannot change. If you don’t change, you become visible, when you are visible, you are “pre-visible”, and Uke can read your actions.

We have to learn hos to change. Then, I began to get very lost when Sensei added that “(he) cannot teach change.”

How then can we possibly learn to change when he cannot teach it?

He explained that it was impossible to teach because change is a natural human reaction that develops by itself. When we watch him doing things that we can hardly copy, there’s no learning process or structure to follow. The ability to change is what blooms from your training.

We see the permanent change when he does it, and maybe, one day, we will be able to do it. It cannot be learned; it comes from years of practice.

That understanding about change, connection, security being the result of years of practice, tied us (Tsunagaru) with his introductory speech about the new Kannon statue.

I have the feeling that Hatsumi Sensei has reached another plateau in the evolution of his understanding of Budō. At this level of Mutō Dori, we are only witnessing his level of expertise.

I wrote in a recent post that we shouldn’t copy his movements. I guess I was wrong because copying him is not possible anymore.

_____________________

1. Tsunagaru: 繋がる, to be tied together; to be connected to; to be linked

Tsunagu: 繋ぐ/tsunagu/to tie; to fasten; to connect

2. Anzen: 安全, safety|security

3. Asobi: 遊び, 1) play, 2) play (margin between on and off, gap before pressing button or lever has an effect)

強弱柔剛あるベからず

強弱柔剛あるベからず Each class, Hatsumi sensei speaks about moving “Yukkuri”, slow. This is different from training slowly. (1)

Each class, Hatsumi sensei speaks about moving “Yukkuri”, slow. This is different from training slowly. (1) I don’t speak Japanese, but I do my best to pronounce it correctly. Too often, I can see t-shirt written “Gyokko Ryū Koshi Jutsu” instead of “Gyokko Ryū KoSShi Jutsu.” (1)

I don’t speak Japanese, but I do my best to pronounce it correctly. Too often, I can see t-shirt written “Gyokko Ryū Koshi Jutsu” instead of “Gyokko Ryū KoSShi Jutsu.” (1)

Don’t be selfish!

Don’t be selfish! This year Mutō dori is about controlling Funiki, your environment.

This year Mutō dori is about controlling Funiki, your environment.