A Guide to Happiness – Kōfuku No Shiori(幸福の栞)

From The Magick & The Mundane » Bujinkan by Shawn Gray

A couple of weeks ago I posted a few of observations about Kōfuku No Shiori on Facebook – posting a longer follow-up here at the suggestion of friends.

A couple of weeks ago I posted a few of observations about Kōfuku No Shiori on Facebook – posting a longer follow-up here at the suggestion of friends.

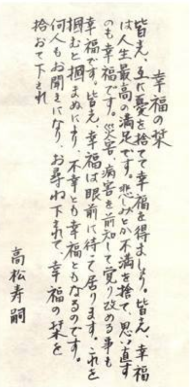

Kōfuku No Shiori (幸福の栞), which translates as “A Guide to Happiness“, is a short text by Takamatsu Sōke. In seeing the Japanese original again recently, a number of things came to mind and I thought it might be good to post an English translation that will perhaps breathe some new life into this well-known and meaningful piece. Here’s the Japanese original:

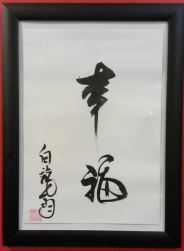

幸福の栞

皆さん、互いに憂を捨てて幸福を得ましょう。皆さん、幸福は人生最高の満足です。悲しみとか不満とかを捨て、思い直すのも幸福です。災害、病害を前知して覚り改めることも幸福です。皆さん、幸福は眼前に持って居ります。これを掴むと掴まぬにより、不幸とも幸福ともなるのです。何人もお聞きになり、お尋ね下されて、幸福の栞を拾おて下され。

Let’s break it down and see what we can find …

1) 皆さん、互いに憂を捨てて幸福を得ましょう。

The first thing that strikes me when I read the Japanese is the use of 皆さん (“Mina-san“), which means all or everyone. It begins the first sentence, and you can see that it appears at the beginning of two other sentences in this text as well. This is interesting because it indicates that Takamatsu Sōke was consciously addressing a group of people – all of the readers. The original context may have been such that it was intended for his own students, or for a specific group, such as a group of Hatsumi Sōke’s students at the time. Nevertheless, when we read it today, we can read it as if it’s addressed to us, the readers, as well. Why is it significant that the text is addressed to everyone? The rest of the first sentence sheds more light on that, beginning with the next phrase, 互いに (tagai-ni), which means together, mutually, or with each other. The opening sentence ends with the verb 得ましょう (emashou), meaning to obtain or to attain, with the verb ending (~shou) being used to further suggest togetherness in the same way that we use the word “let’s” in English (tabemashou = let’s eat; ikimashou = let’s go). So, in writing about Happiness (幸福, kōfuku), the author isn’t simply saying, “Be happy”, he’s saying “Everyone, let’s attain happiness together.” That’s quite a significant difference. There’s more here, too. He also refers to the throwing or casting away (捨てる) of sorrow (憂, urei – also translated as grief, etc) in this same context of togetherness. An accurate rendering of the first sentence in English would thus be, Everyone, let’s together cast away sorrow and attain happiness.

2) 皆さん、幸福は人生最高の満足です。

Once again, he begins with 皆さん, Everyone, and simply states that happiness is the most satisfying thing in life (a more direct, literal rendering would be, happiness is life’s ultimate satisfaction).

3) 悲しみとか不満とかを捨て、思い直すのも幸福です。

Ultimate satisfaction sounds great, right? Everybody wants that! The author recognizes that it’s not that simple – human beings struggle with feelings of sorrow and discontent. The author urges us to find Happiness by discarding those negative feelings and taking another look at our situation. Sorrow (悲しみ, kanashimi) and discontent (不満, fuman) are pretty straight-forward to translate, and although 捨てる (suteru, used above as well) has a wide range of possibilities (such as “throw away, “leave behind”, “discard”, “abandon”, “dispose of”, etc.), I thought “cast away” fit well in this context.

What I found interesting here was 思い直す (omoi-naosu). Omoi is from Omou (思う), “to think“. Naosu (直す) is interesting here because not only does it have the meaning of doing something again (repeating something), but also because it carries the sense of “fixing”, “correcting”, or “repairing” something in the process. For example, in addition to having the sense of repeating something, Naosu is also commonly used to say things like “I’ll fix the chair” or “I’ll correct the issue”.

I’ve rendered Omoi-naosu as “re-thinking” to convey the sense, which I think is implied in the original Japanese, that Happiness is achieved here not only by simply looking back upon sorrow and discontent in life, but by actively choosing to discard sorrow and discontent and re-think (re-frame or “correct”) our perspective on our life experiences. I think Takamatsu Sōke is observing that Happiness doesn’t come from our external circumstances but from the perspective that we choose to take on those circumstances: Casting sorrow and discontent away and re-thinking is also happiness.

4) 災害、病害を前知して覚り改めることも幸福です。

Like the previous sentence, this one is simple, direct, and to-the-point in the Japanese. The first two terms are 災害 (saigai – calamity, disaster, or misfortune) and 病害 (byogai – disease or blight). Saigai can perhaps be understood as the calamity itself, and Byogai as the bodily effects of the calamity. 前知 (zenchi) refers to foreknowledge or anticipation, 覚り(satori) means understanding (but also with the sense of enlightenment or spiritual awakening), and 改める (aratameru) refers to correcting, rectifying, or improving – similar to the idea expressed by Naosu above. Once again, Happiness isn’t a product of our circumstances, but a product of our perspective. Anticipating and correcting one’s understanding of the ravages of calamity and disease is also happiness.

5) 皆さん、幸福は眼前に持って居ります。

Again, 皆さん, Everyone. Again, short and to-the-point: Everyone, happiness is waiting there before your eyes.

6) これを掴むと掴まぬにより、不幸とも幸福ともなるのです。

There are a couple of interesting points here as well. The first is the use of これ (this) at the beginning. What does this refer to? Does it refer to happiness? It could, yes. It could also refer to the previous sentence as a whole, which gives a different sense to what follows: whether you grasp (掴む, tsukamu) this or don’t grasp (掴まぬ, tsukamanu) this. So the phrase could mean a) whether you grasp happiness or not, or b) whether you grasp the point of the previous statement (about happiness waiting there before your eyes) or not. Maybe they’re both the same thing. ;-)

Another interesting point here, I think, is the mention of 不幸 (fukou, unhappiness) as the alternative if you don’t grasp it: Whether you grasp it or not determines your unhappiness or happiness.

7) 何人もお聞きになり、お尋ね下されて、幸福の栞を拾おて下され。

I like the way that Takamatsu Sōke ends this piece. He doesn’t say, “There’s my advice, take it or leave it” or, “That’s the word on finding happiness, there you have it.” He encourages the reader to go out and find the guide for Happiness for themselves by asking (お聞き) and inquiring (お尋ね) of everyone (何人も). Ask others, get opinions, and find it for yourself: Ask everyone, inquire of them, and find the guide to Happiness.

I think these together form a pretty accurate translation of Kōfuku No Shiori:

Everyone, let’s together cast away sorrow and attain happiness.

Everyone, happiness is life’s ultimate satisfaction.

Casting sorrow and discontent away and re-thinking is also happiness.

Anticipating and correcting one’s understanding of the ravages of calamity and disease is also happiness.

Everyone, happiness is waiting there before your eyes.

Whether you grasp it or not determines your unhappiness or happiness.

Ask everyone, inquire of them, and find the guide to Happiness.

Takamatsu Sōke led an adventurous life, but in hearing and reading stories over the years, “happy” isn’t always the first word that comes to mind – at least not when one looks at the external circumstances of his life. But as the wise Ninjutsu master teaches us here, it’s our internal perspective that matters. Looking back over painful or unfortunate circumstances, re-considering, re-thinking, and re-orienting our perspectives can allow us to lead fuller, happier lives. In a recent message I received from Shiraishi Sensei, he referred to ‘the study of Ninjutsu, which creates happiness’. I’m willing to bet that he’s read Kōfuku No Shiori a couple of times.