Ninja and Sake

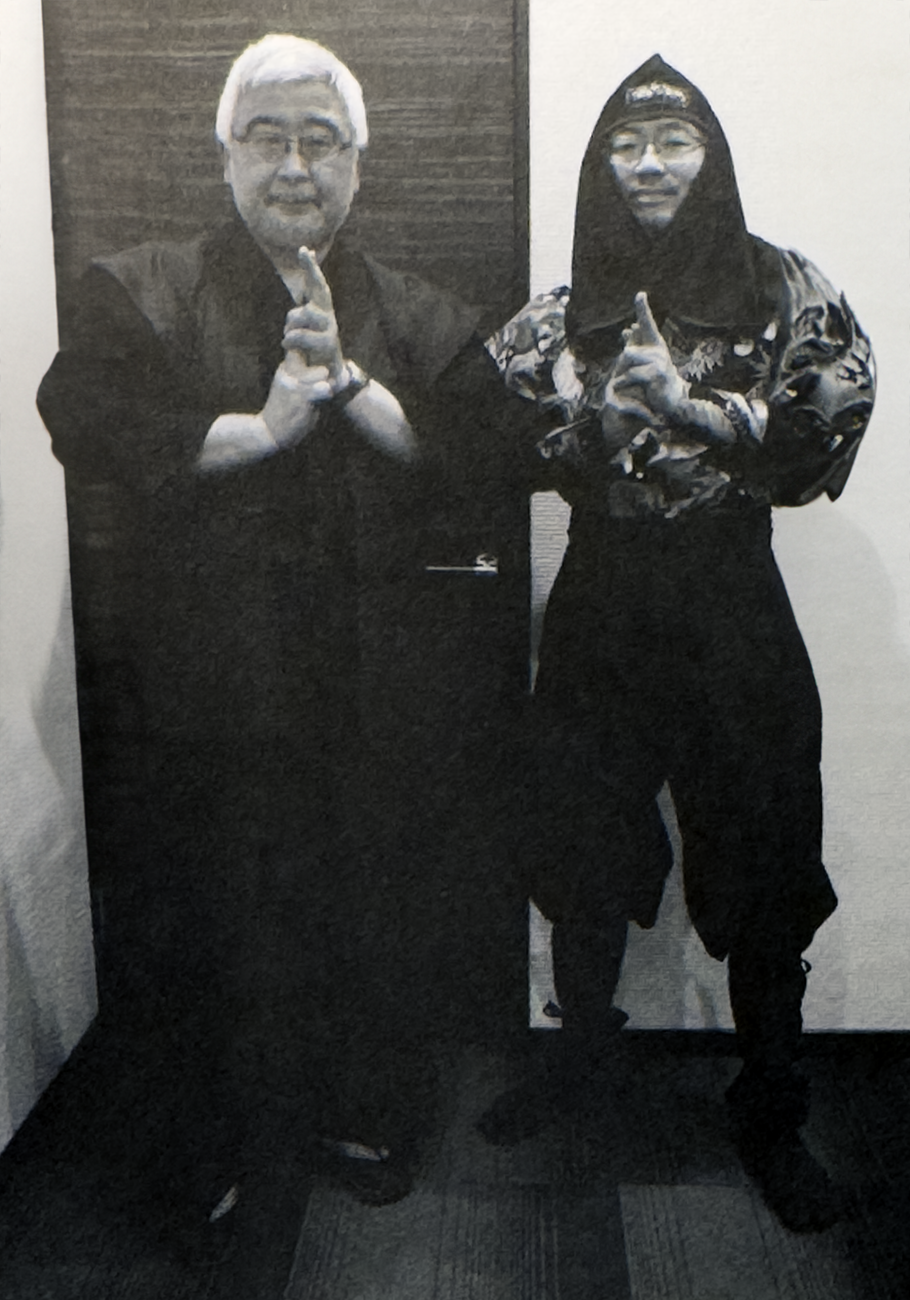

From 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu by Toryu

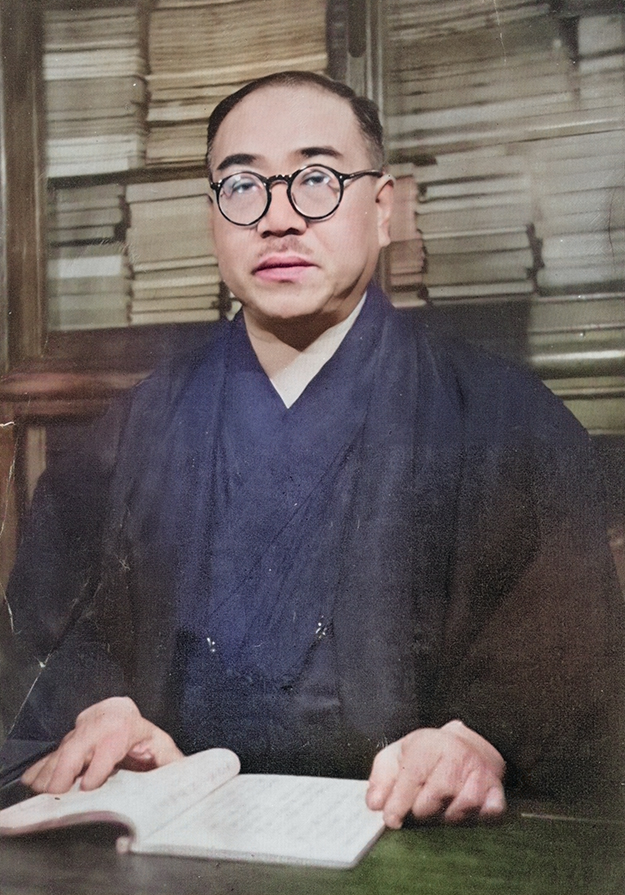

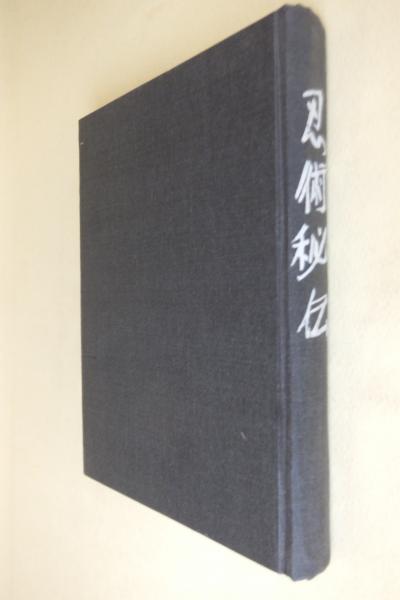

Excerpt about Ninja and Sake from the book Ninjutsu Hiden by Heishichirō Okuse (page 172-174)

I heard this from Master Fujita Seiko, but apparently, to be a ninja, you also need to be quite good at handling sake. There’s not a single mention of sake in the manuals, so there doesn’t seem to be any “special way of drinking,” but given the nature of their profession, ninja had to study every method of winning people over. It’s hard to believe they wouldn’t have used something as convenient as sake for that purpose. However, sake is a tricky thing—if you only encourage others to drink without drinking yourself, it can seem too obvious. In some cases, it might even backfire:

“What’s this? You keep pushing me to drink but don’t touch a drop yourself… What, you’re a teetotaler? Tch, what a boring guy!”

Instead of winning someone over, you might end up being pushed away. This leads me to agree with Fujita’s theory—though it’s not written in the manuals, a ninja must have been a considerable drinker, which seems entirely reasonable.

Now, regarding the drinking capacity of ninja: in the past, among ninja circles, someone who couldn’t drink much was said to be at the 嗅ぐ級 Kagu-kyū (sniffing level). Those who could handle a bit more were at the 嘗める級 Nameru-kyū (licking level). Beyond that, they’d enter the 飲む級 Nomu-kyū (drinking level). You might think the “sniffing” level meant just two or three cups, or at most a bottle (tōkuri (~180 mL to 360 mL), but that would be a huge misconception.

At the “sniffing” level, the minimum qualification was about one shō (roughly 1.8 liters, standard bottle size) of sake. To reach the “licking” level, you had to be able to drink at least five shō (about 9 liters), or you wouldn’t qualify. To be considered at the “drinking” level, you’d need to handle over one to (about 18 liters). And to be called “a good drinker,” you’d have to drink more than three to (54 liters) on your own—otherwise, you’d be labeled a liar.

In 1951 (Shōwa 26), Ueno City held a “Children’s Exposition,” and I was tasked with planning it. During that time, I came up with the idea for a “Ninjutsu Pavilion,” which marked the beginning of my connection with Fujita-sensei. I hope for good relations in the future, but back then, I had the chance to drink with Fujita about once every three days. However, I’m the kind of man who’s “not even fit to stand upwind of a ninja”—after just two or three cups, my face turns bright red. Master Seiko, being a proper ninja, would never get drunk on just one or two shō. When I asked the tactless question, “Sensei, how much can you drink?” he replied with a serious expression,

“Oh, I’m not much of a drinker. Just at the licking level, I suppose.”

After accompanying him four or five times, I realized that Fujita’s drinking capacity perfectly matched the “ninjutsu standard.” Truly, a gentleman knows himself—his capacity was five or six shō.

At five or six shō, he’d never get drunk. I remember thinking,

“Well, at this level, there’s absolutely no worry of being killed by sake,” and I was oddly impressed.

In the past, even the least capable drinkers among ninja likely trained to at least reach the “sniffing” level. If you could drink one shō, you could pretend to be drunk while keeping your wits about you, taking advantage of your opponent’s inebriation to subtly probe their intentions or quickly build rapport by slapping shoulders together—something a ninja could do with ease.

Since hearing that you can’t become a ninja without reaching at least the “sniffing” level of drinking, I’ve completely given up on becoming one. For one, there’s the saying “you need to be alive to enjoy life,” and secondly, as a salaried worker, the “training fees” for such drinking would be a considerable burden.

For these reasons, I’ve limited myself to merely studying ninjutsu.

Excerpt above about Ninja and Sake from the book Ninjutsu Hiden by Heishichirō Okuse (page 172-174)

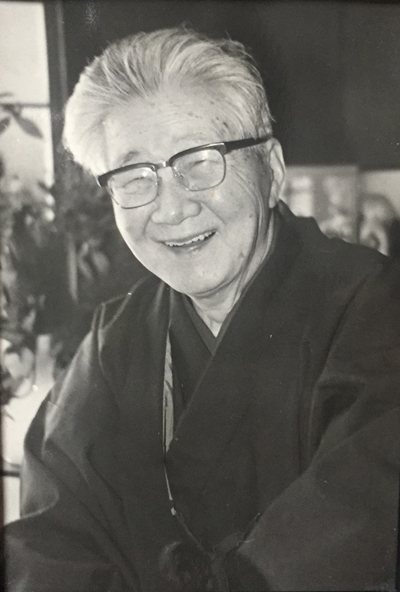

Heishichirō Okuse (奥瀬 平七郎, おくせ へいしちろう) was a Japanese novelist, researcher, and politician born on November 13, 1911, in Ueno, Japan. He passed away on April 10, 1997.

Okuse graduated from Waseda University and studied under the renowned author Masuji Ibuse. He developed a particular interest in ninjutsu (the art of stealth and espionage), contributing to its study and preservation. Professionally, he worked for the Manchurian Telephone & Telegraph Company.

In addition to his literary and research endeavors, Okuse served as the mayor of Ueno from 1969 to 1977. His multifaceted career reflects a deep engagement with both traditional Japanese martial arts and public service.

The post Ninja and Sake appeared first on 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu.…

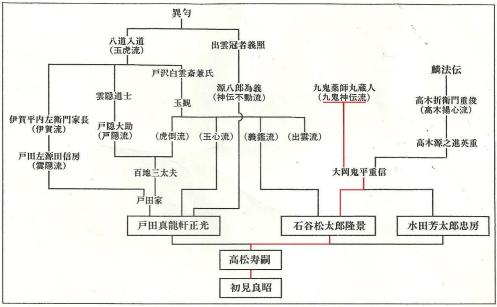

Toda Gosuke is historically recorded as working in the Oniwaban intelligence agency as well as being a head falconer for the Shogun.

Toda Gosuke is historically recorded as working in the Oniwaban intelligence agency as well as being a head falconer for the Shogun.

He was very excited about the finds and insisted that I get everything translated over into Japanese for him right away.

He was very excited about the finds and insisted that I get everything translated over into Japanese for him right away.