From The Magick & The Mundane » Bujinkan by Shawn Gray

February 9th was the 20th anniversary of my first day of training in the Bujinkan. I mentioned it on Facebook, but was encouraged to write a series of blog articles about a bit of my martial arts history and how I found the Bujinkan and made my way to Japan to train with Hatsumi Sensei – to approach the heart of the flower that is Japanese martial arts, budo. I’ve always found it fascinating to hear stories of the adventures of my Sempai here (Mark Lithgow, Michael Pearce, Mark O’Brien, Andrew Young, and Mike L) and, now in my 17th year in Japan myself, I thought it would be fun to look back over the years, and in remembering, share some of that with the readers of my blog.

Black Belt Magazine – Feb 1984

Like many of us in Bujinkan, I was originally attracted by the ninja image. It was 1984, the same year that I started karate practice. In the small town of 3,600 where I grew up in Eastern Canada, there was a Chito-Ryu Karate club, which I joined after 9 years of ice hockey. I quickly came infatuated with Japanese martial arts and would frequently go to the magazine rack at the local gas station to check for the latest issues of martial arts magazines. It was on one of these visits that I found Black Belt Magazine, Feb 1984 issue. I was young. I was impressionable. I was hooked.

But how was a young New Brunswick lad supposed to access this ninja training? I was in junior high school. I couldn’t go to Japan. I couldn’t even go to Dayton, Ohio. But I could join the Shadows of Iga Society and Robert Bussey’s Warrior International as a correspondence member, so that’s what I did. I also got hold of some Japanese split-soled tabi boots and shuko hand claws and spent a lot of time running around in the woods climbing trees and sneaking up on unsuspecting neighbours and making blowguns from copper pipe. Luckily, I survived. Sometimes that rather surprises me.

I kept up with my karate practice quite seriously, entering and coming home with trophies from a number of provincial tournaments. I was invited to go to the Canadian national championship tournament, but it was held in Vancouver, 4,000km away, and I was in high school. I entered a local college and took liberal arts courses, and in my second year was presented with the opportunity to take a year off my studies and go to teach English in Japan. It was a dream come true, needless to say, and in August 1990 at age 19, I got on a plane and flew to the other side of the world, from a town of 3,600 to a city of 25 million.

I somehow managed to find the people that were meeting me at Narita airport. They had come by car to pick me up, and I remember that traffic was absolutely gridlocked all the way back to Tokyo. A trip that would take an hour by train took us six hours by car. After having already traveled through a 15-hour time difference in 24 hours, it seemed to take forever. We finally arrived at the organization’s Tokyo headquarters in Shinjuku, where I stayed for the first 3 days for an orientation program. Shinjuku is one of the major Tokyo metropolitan centers and one of the biggest train stations in the world, and having come from such a small town it amazed me that I had to look straight upwards to even see the sky. There were so many skyscrapers and so many people and so much concrete and so many wires and lights and sounds – I was at first afraid to even go exploring outside alone because I thought I’d get lost and never be able to find my way back (most of the streets in Japan don’t have names). The city seemed to go on forever. This wasn’t like visiting another city, or even another country. It was like visiting another planet entirely. Planet Japan.

Atomic Bomb Memorial, Hiroshima

After the 3-day program in Shinjuku finished, I boarded a Shinkansen high-speed bullet train bound for Hiroshima, where I had been placed to work as an English teacher. The ride took around 5 hours from Tokyo back then, I think (it might be a little quicker now). The train sailed along so quickly and smoothly it felt like I was riding in an airplane. I was going to be one of the first occupants in a newly-constructed apartment building that was going up near the place I’d be working, 30 minutes out of central Hiroshima by bus. Since construction wasn’t finished yet, I stayed in an apartment in downtown Hiroshima for the first month – right across the street from Peace Park, ground zero for the atomic bomb that had been dropped there 45 years before. I could see the famous bombed dome monument from my kitchen window, and would often go walk through the park to sketch, practice my haiku, or just people and pigeon watch. When I saw something interesting, I’d sketch it or write about it in a journal. (I didn’t blog it. I didn’t Facebook it. I didn’t Twitter it. It was pre-Internet, and life was good.) Peace Park also had an international cultural center where I could get travel and tourism tips in English, and also watch news on TVs with English subtitles. I remember taking the 30-minute bus ride in to Tokyo to keep up with the first Gulf War (the Bush’s first attempt at Hussein) on their TVs. They also had a library with a lot of English books about Japan – but you couldn’t check them out, you had to read them in the library. It was here that I discovered Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor and film director Yukio Mishima, and with my interest in Bushido, the way of the Samurai, I was fascinated to discover that his failed coup d’etat and suicide by ritual disembowelment occurred literally 2 hours before I was born. (The things that fascinate 19-year-old Bushido enthusiasts!) The library also had a copy of Yoshikawa’s Musashi, the life story of the famous samuraiwarrior. It was quite a thick book, and since I couldn’t take it home with me, I went back again and again, gradually working my way through it. I was completely enamored with bushido, the samurai code of honour.

One of my first memories in Japan, while settling into my English teaching schedule and still living across from Peace Park, was of one of my neighbours – an interesting American guy named Richard (no, that’s not him in the photo, that’s me, trying to teach English). After I’d been there some time, Richard announced that he was going on a trip to China and asked me if I’d look after his place while he was away. Turns out while he was in Hong Kong he found out that there was a film production looking for extras and he applied and got a part in the film. The movie was Kickboxer with Jean Claude van Damme. (Richard is the reporter who interviews “the champ” after the match right at the beginning of the film.) I wasn’t much of a movie buff and didn’t realize what a big film it was until later. I later moved out to my apartment in the suburbs and we eventually lost touch, unfortunately. I should look up his name in the movie cast members and see if he’s on Facebook. That would a riot. (I wonder if he signs autographs…) Another interesting memory was the time that he told me that he was going to be away for a couple of days to go talk to someone regarding a misunderstanding that he was having with a gangster who thought he was seeing his girlfriend. I was supposed to call the police if he wasn’t back in 2 days. I hadn’t even been in Japan a month yet and already I was making such interesting friends. :)

One of my first memories in Japan, while settling into my English teaching schedule and still living across from Peace Park, was of one of my neighbours – an interesting American guy named Richard (no, that’s not him in the photo, that’s me, trying to teach English). After I’d been there some time, Richard announced that he was going on a trip to China and asked me if I’d look after his place while he was away. Turns out while he was in Hong Kong he found out that there was a film production looking for extras and he applied and got a part in the film. The movie was Kickboxer with Jean Claude van Damme. (Richard is the reporter who interviews “the champ” after the match right at the beginning of the film.) I wasn’t much of a movie buff and didn’t realize what a big film it was until later. I later moved out to my apartment in the suburbs and we eventually lost touch, unfortunately. I should look up his name in the movie cast members and see if he’s on Facebook. That would a riot. (I wonder if he signs autographs…) Another interesting memory was the time that he told me that he was going to be away for a couple of days to go talk to someone regarding a misunderstanding that he was having with a gangster who thought he was seeing his girlfriend. I was supposed to call the police if he wasn’t back in 2 days. I hadn’t even been in Japan a month yet and already I was making such interesting friends. :)

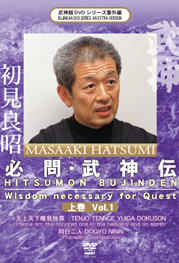

I soon got into the swing of things with my weekly schedule of English classes – class size varied, but I think overall I had 90-100 students per week. After the work schedule was sorted, I started getting to know my way around my new neighbourhood bit by bit and began to explore the wonderful, exotic treasures of Japanese culture: go,(the board game), sado (tea ceremony), shodo (calligraphy) and, of course, budo, Japanese martial arts. The first thing on my list for that last activity was to make contact with my karate sensei – and the next was to track down the ninja master Masaaki Hatsumi.

(To be continued in Part II…)

…