Noguchi Sensei: Happiness, Basics And Creativity

From Shiro Kuma by kumablog

Buddha said that “thousands of candles can be lighted from a single candle, and the life of the candle will not be shortened. Happiness never decreases by being shared.”

This sentence is resuming my feeling entirely during Noguchi sensei’s class, on Sunday morning. Anyone who trained in Japan knows how “foggy” you feel during this first class beginning the training day. In the old days, this class used to happening after Sensei’s class. But less and fewer people would come, so they changed the order. We now have to wake up earlier.

To me, Noguchi sensei is a candle of happiness, even though his life has been tough at some point. (1) These events could have destroyed his happiness. It didn’t happen. The Bujinkan is about being happy and to keeping going whatever hardship one meets in his or her lifetime.

Sunday, I was glad to meet my teacher again after my last Japan trip in April. (2) But to be honest, I was a little sleepy after a short jet lag night. This tiredness vanished after the first movements, as his permanent happiness spread all over the dōjō, and motivate everyone. The light of happiness spreads in all directions, and everyone is in the light.

I love Noguchi sensei’s creativity and the way he reinterprets the well-known Waza and basics of the Bujinkan. This ability to do something new with old known techniques is amazing. It has nurtured my whole Budō approach for nearly a quarter century now. I owe him a lot for the level I have today.

Sunday we rediscovered some basic techniques of the Tenchijin. (3)

We began the class with the Tonsō no Kata (4), the escaping techniques of the Tōgakure Ryû. Those nine Waza are the essence of the school and are much more than one thinks at first glance.

There are 3 sets of 3 simple techniques. The first three Waza, deal with taijutsu; the second set of three, with Mutō Dori, the last three with strategy when facing multiple opponents.

“When dealing with multiple opponents, always attack the weakest one first”, said Noguchi sensei.

If some of the techniques use Metsubishi and Shuriken, to me, this is not the important lesson. I see the Tonsō no Kata more like the Juppō Sesshō of the Tōgakure Ryû.

We continued with the Suwari Waza from the Jin Ryaku no Maki, but we did them standing up. That is where his creativity became visible. Playing with the concept of Juppō Sesshō, we did those techniques in an entirely new way, changing the angle of the grip in the ten directions. It was refreshing and reinforced our feeling of happiness.

Then we moved to the Nage Kaeshi part, reviewing Okyō, Zu Dori, Fûkan. The Okyō was entirely different from the basic form I knew. Instead of the simultaneous double hits (chest and lower back), Noguchi sensei, rotated the upper torso to the left at the start of the throw, destroying Uke’s Nage Waza, and turning it into a soft but efficient Ô Soto Gake. That was effortless and beautiful.

We finished with some creative Hanbō Jutsu starting from Kata Yaburi no Kamae (5)(6) and Otonashi no Kamae. (7)

Once again, I want to emphasize that, when you come to Japan, you have to know your basics before leaving your country as you will not train the fundamentals here, only their evolution.

If you know your basics, learning their new interpretations is easy. But if you don’t, you cannot understand the Waza and will have a wicked sense of knowledge mixing the primary forms with the advanced Henka.

For the light of the candle of happiness to shine, you first need to get a candle. Learning the Tenchijin and the schools is how you get your candle ready for the light.

__________________________________

- Noguchi sensei was born the same day as the Hiroshima bomb destroyed the city, his elder brother was killed during the war, and his beloved son died a few years ago at age 36.

- For some reason, 24 years ago, in July 1993, Hatsumi sensei asked me to train exclusively with him and Noguchi sensei. Noguchi sensei became my teacher.

- A new reprint of the original Tenchijin has been released in Spanish (the English version should be released very soon), check the Shinden Ediciones by my friend Fernando Aixa, Jûgodan. Without a doubt, the best-published version so far. A must-have for any serious practitioner.

- 遁走/tonsō/fleeing; escape

- Kata Yaburi no Kamae is often called Hiraichimonji no Kamae in basic programs.

- 型破り/katayaburi/unusual; unconventional; mold-breaking

- 音無しの構え/otonashinokamae/lying low; saying nothing and waiting for an opportunity

“Mutō Dori is not about fighting; it is about controlling.”

“Mutō Dori is not about fighting; it is about controlling.”

A week ago, my last class with Sensei for this trip was another great one, with many insights to bring and to train at home.

A week ago, my last class with Sensei for this trip was another great one, with many insights to bring and to train at home. When Hatsumi Sensei saw this statue at his regular antique shop, he took it as a reminder of Takamatsu sensei’s story. For him, this statue placed at the centre of the Shinden symbolises the fact that we (he) have reached the level of Takamatsu sensei’s understanding.

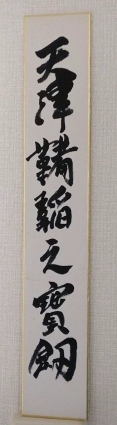

When Hatsumi Sensei saw this statue at his regular antique shop, he took it as a reminder of Takamatsu sensei’s story. For him, this statue placed at the centre of the Shinden symbolises the fact that we (he) have reached the level of Takamatsu sensei’s understanding. Before we did the salute, Sensei facing the Shinden called me to give me a Ōmamori from the Amatsu Tatara. It reads “Amatsu Tatara no Hōken”. Hōken is the treasure sword that protects from sickness and evil. That was a kind attention.

Before we did the salute, Sensei facing the Shinden called me to give me a Ōmamori from the Amatsu Tatara. It reads “Amatsu Tatara no Hōken”. Hōken is the treasure sword that protects from sickness and evil. That was a kind attention.