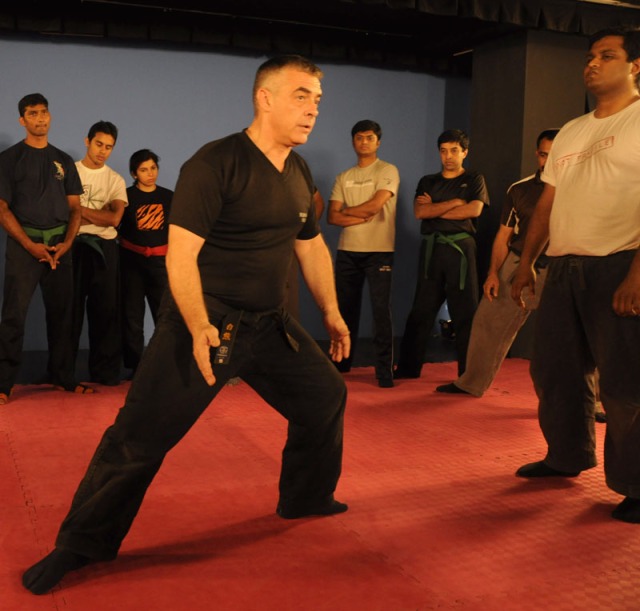

From Shiro Kuma's Blog by kumablog

Being a student of the Bujinkan Martial Arts system is not easy and requires a lot of commitment. You have to keep the connection with everything, learn, memorize, and always be eager to improve your skills. This is a long path but it is worth it.

The life of a Bujinkan practitioner can be seen as a glass of water in which you pour the desired quantity of liquid. The water level in the glass will only depends on you.

If you want to drink water, you will have to define three things:

How much water do you have in the jug.

How thirsty you are.

How big the glass is.

If we compare the glass of water to training, we can see the Bujinkan martial arts like a huge jug of water. First you have to understand that it is your responsibility to “drink” it (and not your teacher’s).

A teacher is like the jug of water. A sensei is an older practitioner who has been thirsty long before you (see the meaning of sensei)*; and who learnt to quench his thirst. Because he “experienced” this, he is now capable of explaining it to you. But if you are not thirsty or committed to learn, you will not drink. Whatever you chose to do is always your choice. Your sensei will not be thirsty for you.

Your brain can “drink” more than you think as long as you believe you can learn and improve. Even if you have a small glass you can learn a lot, you simply have to refill the glass many times until your thirst is satisfied. But to be satisfied requires high expectations. Sadly many students stop training after black belt because this is what they wanted (low expectations). But Shodan is nothing, it is only the beginning. Be thirsty!

This “water sanshin” of the “jug-thirst-glass” is another way to understand the concept of Sainô Konki (ability-soul-container). The soul wants to drink and prepares the glass (container) to receive the ability (water) through long training because the path is long.

The Bujinkan path follows three steps:

1) learn the basic forms (kihon, waza);

2) turn them into situations (kata),

3) in order to forget them and to be yourself.**

Before forgetting the forms you have to remember a lot of them. Your kamae (attitude) in that respect, is important. If you don’t pay attention to the details and go with the “in ninjutsu we can do anything we want” that we often hear, then you will go nowhere. You have to be curious of everything. As Richard Whately said “Curiosity is as much the parent of attention, as attention is of memory.”

Without curiosity/attention/memory you will simply mimick the movements and never reach the ura of things. What Hatsumi sensei is teaching

us is not a set of techniques but an ability to discover and understand the world by ourself. This is why kokoroe is vital. You have to learn and memorize.

Everyone one of us uses clocks, watches, or a phone to know the time, but when those tools are missing (or more likely when the batteries

are dead) do you know how to estimate the time and direction like a real ninja?*** I guess not: this is what “curiosity” is about, always having a “plan B” for everything you do.

When in the army I learnt those things, and even today where GPS devices are available, we still train with the compass and the map.

This the “just in case Murphy was right” attitude.****

In the Bujinkan we have a huge collection of techniques (our “jug of water”).

The techniques are first taught as basics in the Tenchijin. This is our compass and map. But then the second step is to learn them “anew” in their original Ryû. Now, even though some of these fighting techniques are included in the basic Tenchijin that we studied, they change completely when reinserted in their original system. A Ryû presents the waza in a very specific order because in each level the second technique is the evolution of the first; the third of the second etc. Ignoring that will get you misled and you will never get the kokoroe***** of fighting in this specific system.

One you have done that with the Tenchijin and the Ryûha, and with the weapons you are entering the third level of training where things are not decided but come naturally to you. You have learnt to surf the flow of possibilities and became able to survive by your own ability. But until you reach this third level, everything you will try to do will be unnatural, forced and lack nagare. Someone once said: “How is it one careless match can start a forest fire, but it takes a whole box to start a campfire?”. And this is exactly where you will arrive if you forget before studying; think before act; and want before accepting the natural flow of the Universe.

The Universe is there to serve you as long as your ego is not in the way. Stop with the “I want to do a natural technique” and move to “I flow with nature”. Remember the concept of 真如, Shinyô (the ultimate nature of all things)******

_______________________________________________

*先生, sensei means “the (one) born (in the art) before (you).

** do you remember the last glass of water you drank? no, once you drank it, you forgot about it. Techniques are the same, you learn them to forget them more efficiently.

*****kokoroe is knowledge (see previous posts)

******Shinyo (tathatâ in sanskrit). In “Advanced Stick Fighting”, book by Hatsumi sensei, P38, Kodansha Edition or the definition here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tathat%C4%81

…

The Swedish Bujinkan Federation asked Christer Westberg and Petter Swedin during the Taikai in Gothenburg if they wanted to organize the 2014 Taikai in Sundsvall. We are happy they accepted and soon you will see some updates on this web site with more information.

The Swedish Bujinkan Federation asked Christer Westberg and Petter Swedin during the Taikai in Gothenburg if they wanted to organize the 2014 Taikai in Sundsvall. We are happy they accepted and soon you will see some updates on this web site with more information.