History of Ninjutsu: Three Last Ninja

From 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu by Toryu

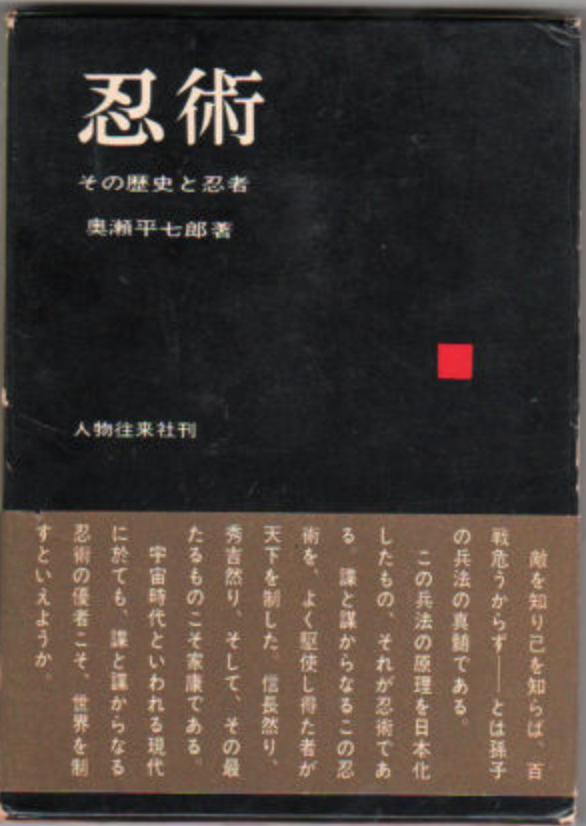

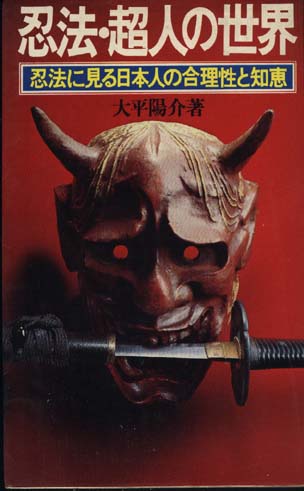

Three Last Ninja Excerpts from the book Ninpō Chōjin no Sekai by Ōhira Yōsuke.

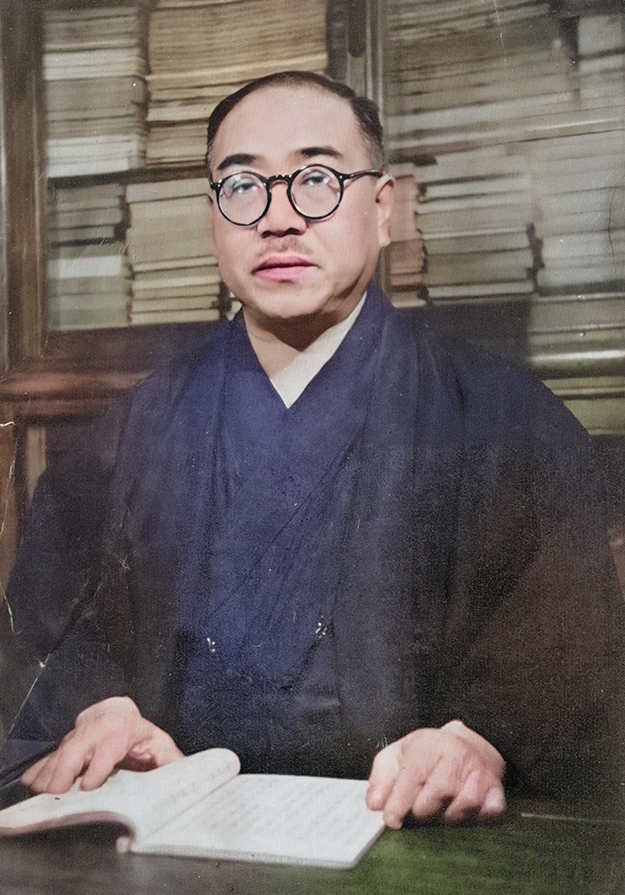

戸隠流 Togakure-ryū 三十三代 33rd Generation 高松寿嗣 Takamatsu Toshitsugu part 1. (Page 64)

At thirteen years old, he obtained the full mastery license of 柔体術 Jūtai-jutsu.

In Meiji 22 (1889), he was born in 兵庫県 Hyōgo-ken, 明石市 Akashi-shi. From nine years old, under his grandfather 戸田真竜軒正光 Toda Shinryūken Masamitsu, he received instruction in 虎倒流骨指術 Kotō-ryū Koppojutsu, and four years later, he endeavored to master 戸隠流忍術 Togakure-ryū Ninjutsu.

Additionally, from 石谷松太郎隆景 Ishitani Matsutarō Takekage, he was taught secret transmissions of 白雲流隠身術 Hakuun-ryū Inshin-jutsu, 八法秘剣術 Happō Hiken-jutsu, 義鑑流骨法術 Gikan-ryū Koppō-jutsu, and others.

In childhood, he was frail and a crybaby, but possessing natural talent recognized by his grandfather, at thirteen years old, he obtained the full mastery license of 不動流柔体術 Fudō-ryū Jūtai-jutsu.

That same year, three delinquent boys provoked him, and he threw them all down. These belonged to a delinquent group called 敷島国 Shikishima-koku, and in retaliation, fifty or sixty delinquents ambushed him in the dark, but he threw them all down, sustaining not a single scratch. This incident became widely known, reported in local newspapers as “The Thirteen-Year-Old Judo Master!” causing a great uproar.

戸隠流 Togakure-ryū 三十三代 33rd Generation 高松寿嗣 Takamatsu Toshitsugu part 2. (Page 85)

Youth Era Called a Hermit or Heavenly Dog.

Under grandfather 真竜軒 Shinryūken and 石谷松太郎 Ishitani Matsutarō, he accumulated training in 忍術 Ninjutsu and 八法秘剣 Happō Hiken, and at nineteen years old, he secluded himself in the depths of shame, devoting himself to mental and physical training.

At this time, he developed clairvoyance-like supernatural abilities, and being called a hermit or 今天狗 Kon Tengu by people, it is interesting that there is a connection with the case of 藤田西湖 Fujita Saiko (see the column described later).

At twenty-one years old, he descended 摩耶山 Maya-san, crossed to the Chinese continent, and while staying in 天津 Tenshin, was recommended as president of the 北支那 Kita Shina Japanese Youth 武徳会 Budōkai.

In this era, at the suggestion of a high-ranking 支那 Shina government official, he fought a one-on-one match with 張 Chō, the foremost master of 支那拳法 Shina Kenpō, with equal strength, continuing the struggle for several hours without a decision, resulting in a draw, and they made a brotherly pact.

Returning to Japan at thirty years old, he settled in 奈良県檜原市 Nara-ken Hiwara-shi, running a diner while living a hermit’s life in his later years, guiding juniors, and passed away in Shōwa 47 (1972) at eighty-five years old.

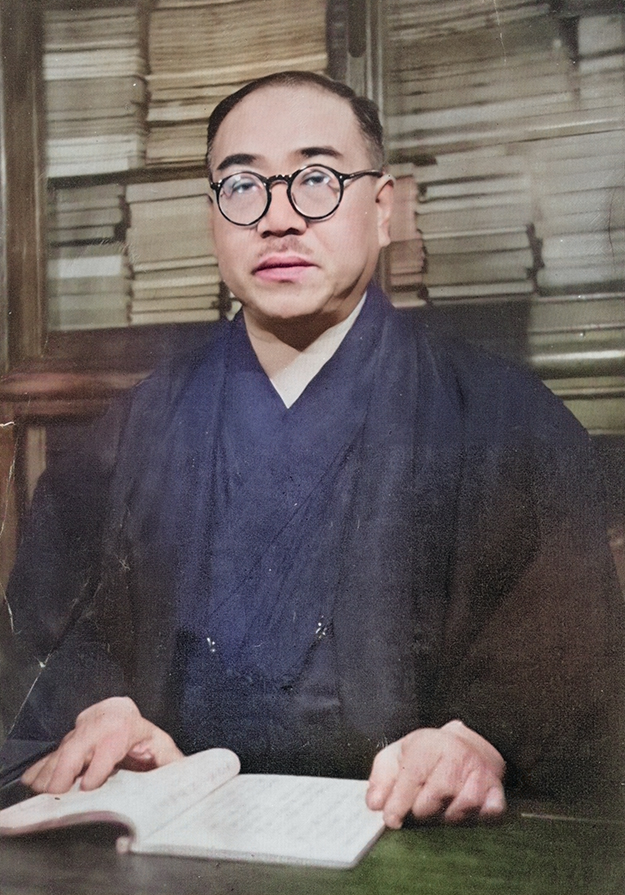

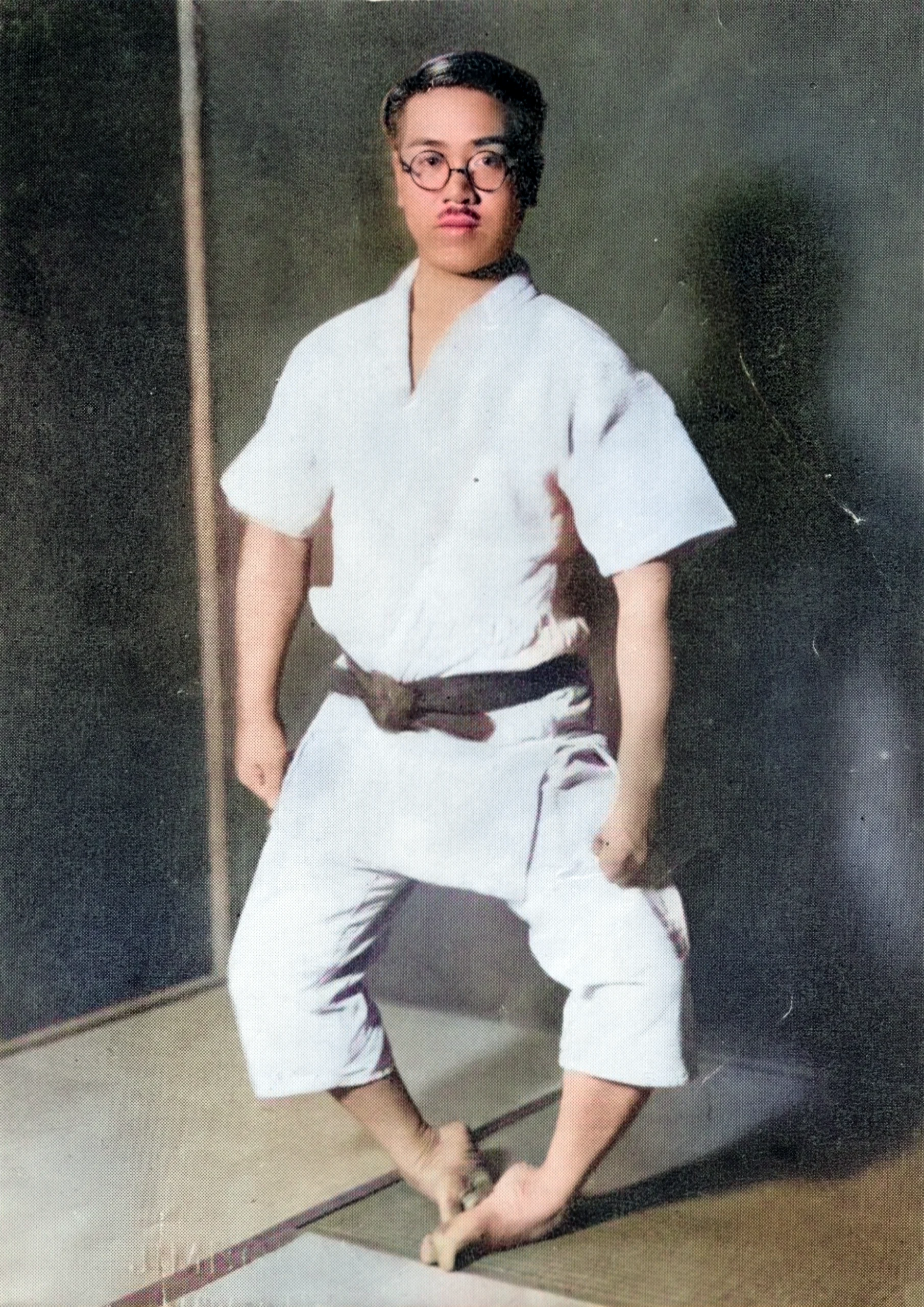

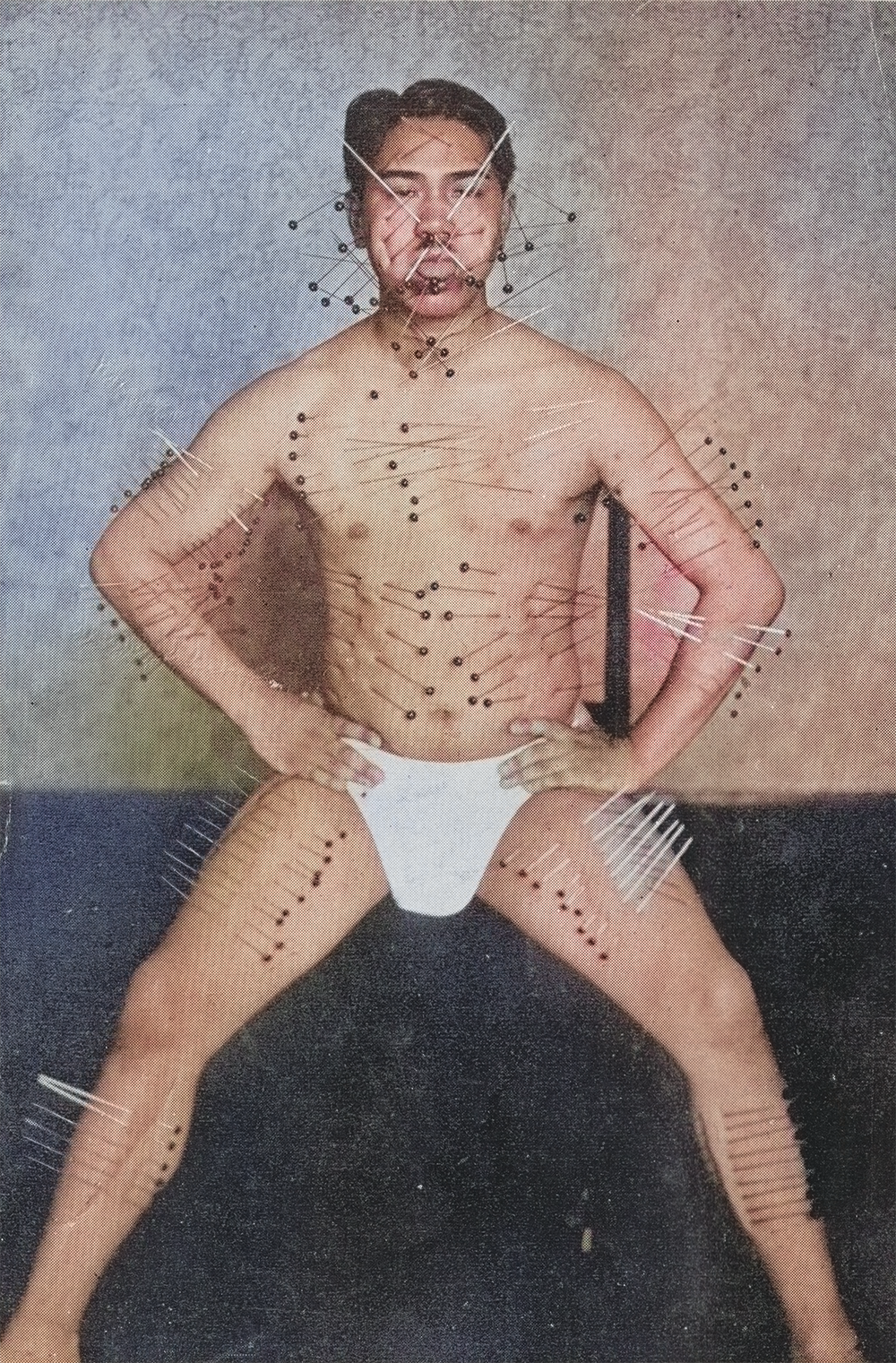

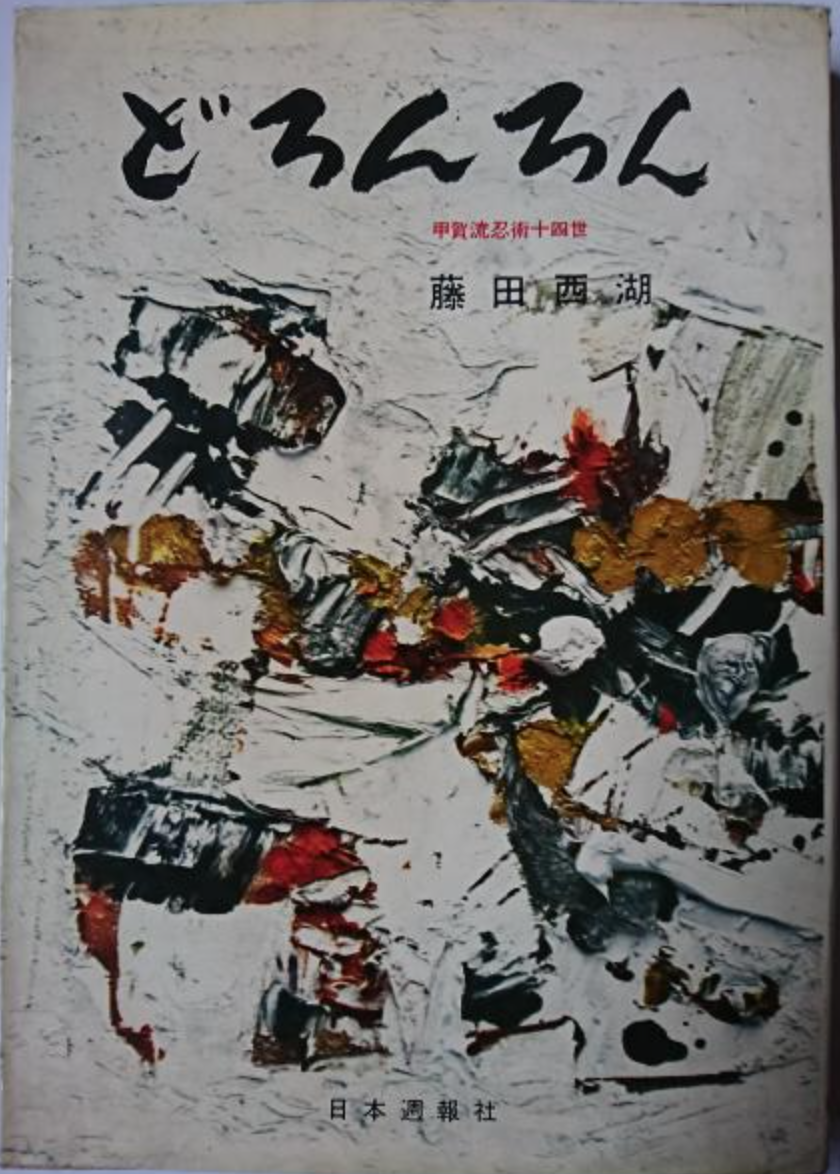

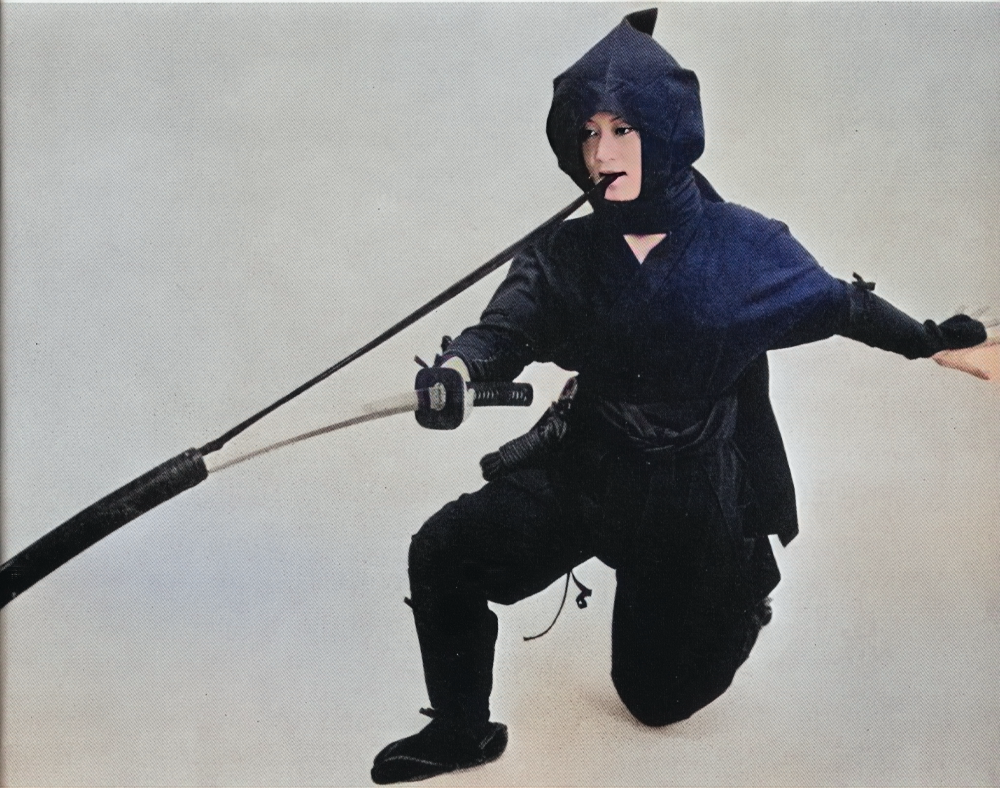

甲賀流 Kōga-ryū 十四世 14th Generation 藤田西湖 Fujita Saiko part 1.

(Page 126)

Father is “Demon Detective.” Master of Music and Flower Arrangement

Real name is 藤田勇 Fujita Yū. In Meiji 32 (1899), he was born in 東京 Tōkyō, 浅草 Asakusa. His real father 森之助 Morinosuke was a detective of the 警視庁 Keishichō, renowned as a master of 捕縄術 Hojōjutsu, dominating an era.

As the great boss of pickpockets, feared throughout Japan, 仕立屋銀次 Shitaya Ginzō, or when serving at the 青梅 Ōme resident police post, he conducted a sweeping crackdown on mountain bandits nesting in the 奥多摩 Okutama to 秩父 Chichibu mountains, and was sung in a ditty’s lyrics as “Detective 藤田 Fujita is scarier than a demon.”

His ancestors were, for generations, distinguished secret agents of the 徳川家 Tokugawa-ke, descending from 和田伊賀守 Wada Iga no Kami, said to be one of the 南山六家 Nanzan Rokuka or six great names among the 甲賀流五十三家 Kōga-ryū Gojūsanka, and at six years old, recognized by his grandfather, the 十三世 13th soke, he began 忍術 Ninjutsu training, enduring hardship and later inheriting the 十四世 14th soke.

Besides learning 拳法 Kenpō, 柔術 Jūjutsu, 槍術 Sōjutsu, 長刀 Naginata, 棒 Bō, 十手 Jitte, 手裏剣 Shuriken, and other martial arts from his grandfather and 橋本一夫斎 Hashimoto Ichifusai, he mastered the essence of 茶道 Chadō, 生け花 Ikebana, 音曲 Ongyoku, 舞踊 Buyō, 書画 Shoga, and others under respective masters. 西湖 Saiko is his artist’s name for painting.

甲賀流 Kōga-ryū 十四世 14th Generation 藤田西湖 Fujita Saiko part 2.

(Page 149)

He was also the instructor of ルバング島 Rubangu-tō returnee soldier 小野田元少尉 Onoda Moto Shōi!

At seven years old, as a clairvoyance ability holder, he was discovered by 博士 Doctor 福来友吉 Fukurai Tomokichi, an authority in that field, and seized the attention of the mass media at the time.

Now called superpowers, but with clairvoyant power and accurate prophecies, at twenty years old, he was deified as a “living god” and greatly prospered. Money came in abundantly, but unable to play at cafés, it was extremely confining. Even if he tried to escape, the surveillance of his entourage was strict, and finally, riding the darkness of night, he fled to 大阪 Ōsaka—this was said to be the first practical use of 忍術 Ninjutsu.

His education was from 早稲田実業 Waseda Jitsugyō to graduating from 日大宗教科 Nichidai Shūkyō-ka. He worked as a reporter for 報知 Hōchi, 日日 Nichinichi newspapers, and from Taishō 11 (1922), served as a martial arts instructor at 陸軍戸山学校 Rikugun Toyama Gakkō, 陸士 Rikushi, 陸大 Rikudai, and other institutions, and from Shōwa 12 (1937), when the 陸軍中野学校 Rikugun Nakano Gakkō was established, he became an instructor teaching 忍術 Ninjutsu.

小野田少尉 Onoda Shōi, who returned from ルバング島 Rubangu-tō after thirty years, was also his student.

In Shōwa 41 (1966), January, he passed away at sixty-eight years old, his grave is at 飯泉山勝福寺 Iizumi-yama Shōfuku-ji in 小田原市 Odawara-shi, his posthumous name is 六大院無礙西湖大居士 Rokudai-in Muge Saiko Dai Koji.

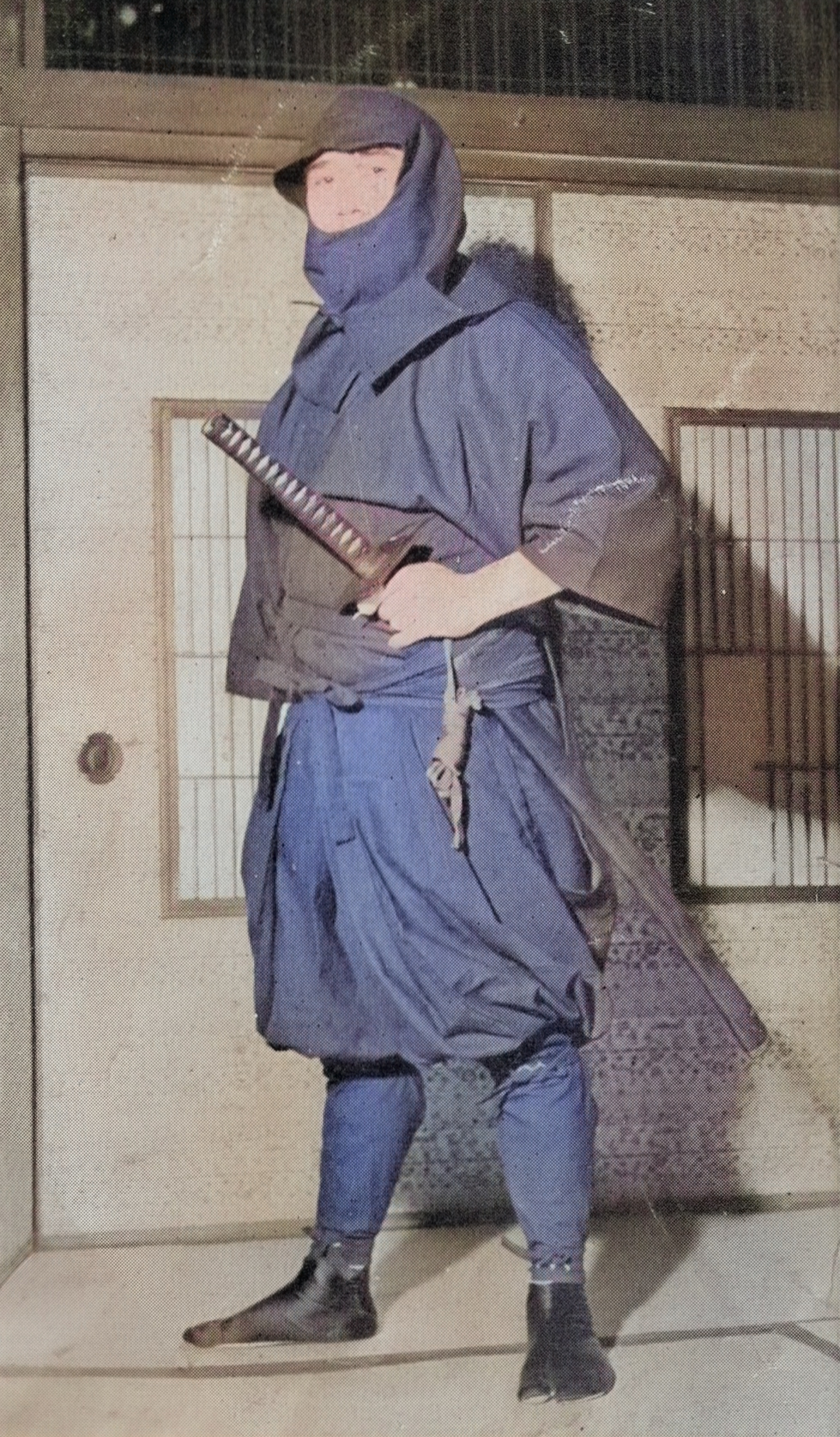

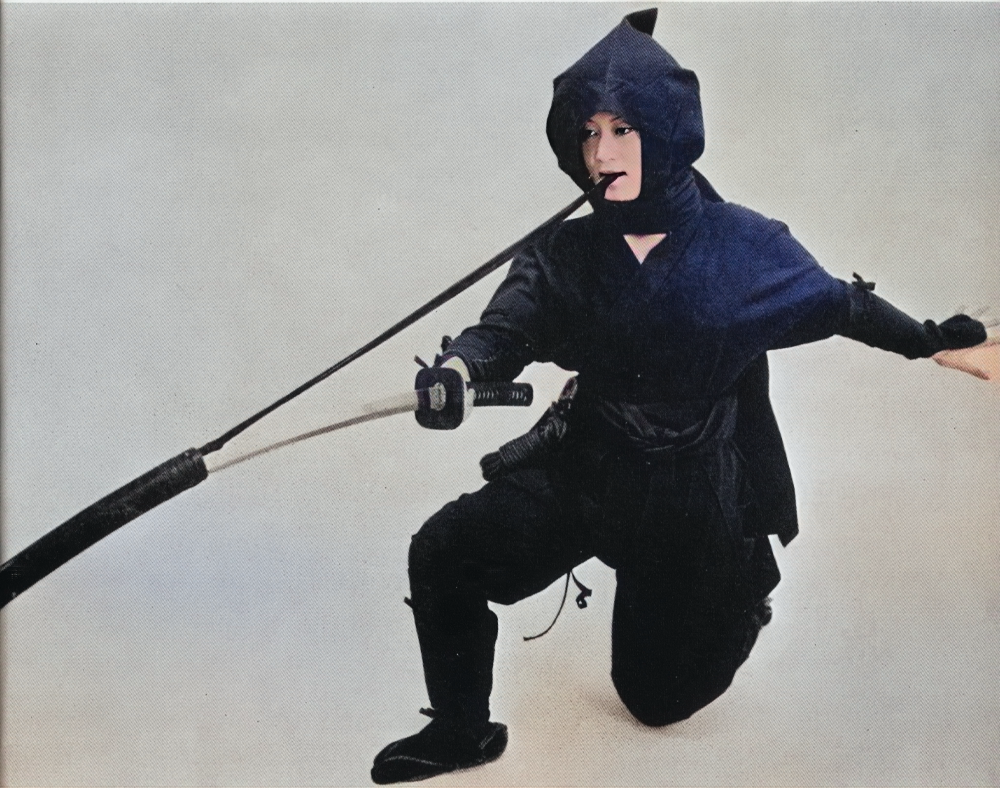

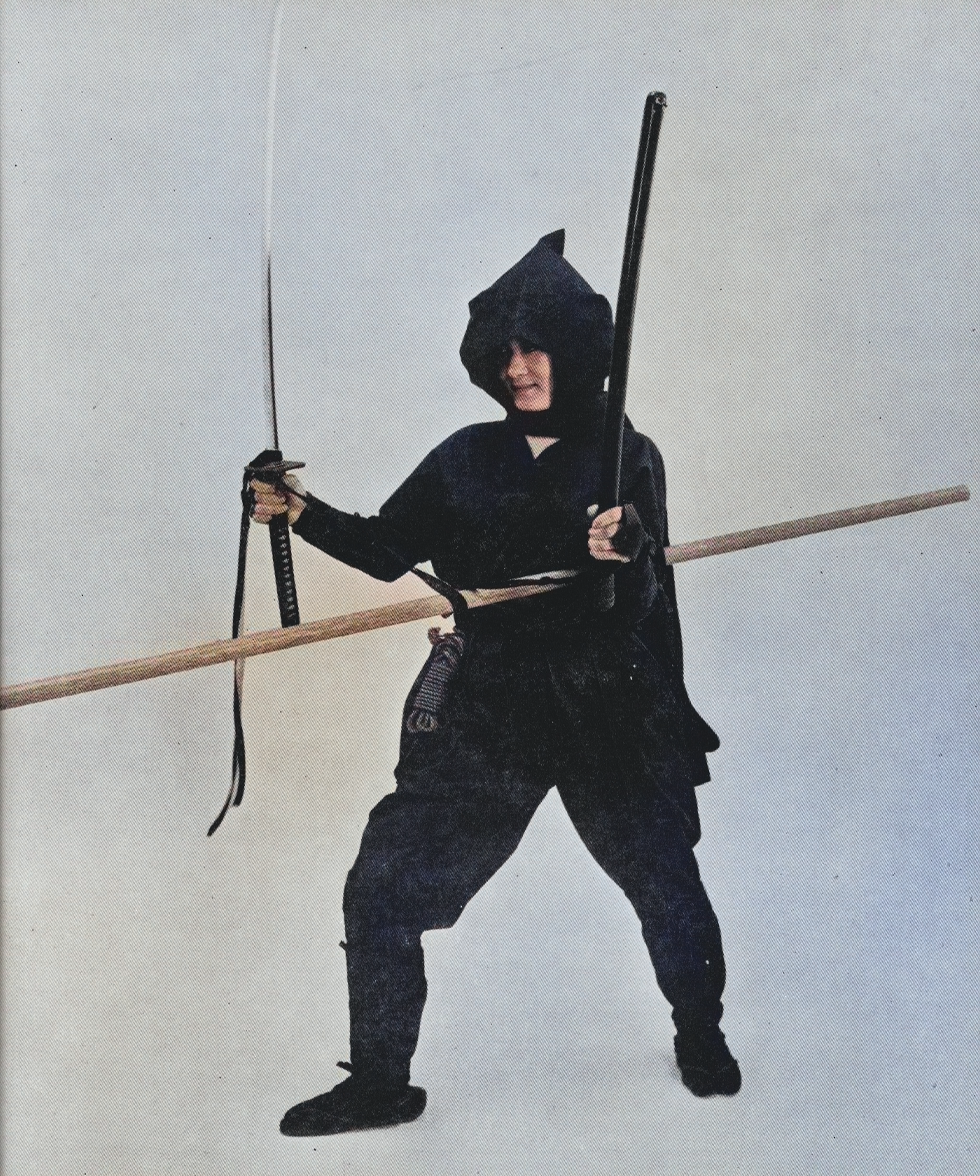

戸隠流 Togakure-ryū 三十四代宗家 34th Soke 初見良昭 Hatsumi Yoshiaki Part 1. (Page 205)

A Genius Recognizes a Genius

In Shōwa 6 (1931), December, he was born in 千葉県 Chiba-ken, 野田市 Noda-shi. He graduated from 明治大学文学部 Meiji Daigaku Bungaku-bu and then from 高等針医専門学校 Kōtō Shini Senmon Gakkō in 四谷 Yotsuya. From elementary school, he loved sports and martial arts, studying 空手 Karate, ボクシング Bokushingu, 剣道 Kendō, 柔道 Jūdō under respective masters, but ultimately realized that the essence of martial arts lies entirely in 古武道 Kobudō, and underwent rigorous training under prominent martial artists while traveling various provinces.

“There is nothing more for me to teach you. For anything beyond this, seek instruction from 高松寿嗣先生 Tak松 Toshitsugu-sensei in 奈良 Nara,” one of his masters suggested, and in Shōwa 18 (1943), he visited 高松先生 Tak松-sensei residing in 奈良県橿原 Kashihara-ken.

高松先生 Tak松-sensei, upon seeing 初見氏 Hatsumi-shi at first glance, recited a seven-syllable quatrain poem ending with “神州人あり、待つこと久し Jinshū hito ari, matsu koto hisashi” to welcome him, it is said.

The 老師 Rōshi, lamenting that there was no suitable successor to pass down the tradition and that the 戸隠流 Togakure-ryū lineage, continuing unbroken since the 徳川 Tokugawa era, might end, upon seeing the rare genius 初見氏 Hatsumi-shi, this poem spontaneously burst from his mouth, it seems.

戸隠流 Togakure-ryū 三十四代宗家 34th Soke 初見良昭 Hatsumi Yoshiaki Part 2. (Page 236)

Dojo Master with Disciples in Seven Countries of the World

Greatly inspired by the acquaintance of 高松老師 Tak松 Rōshi, 初見氏 Hatsumi-shi regarded this person as a lifelong master and devoted himself, traveling from 千葉 Chiba, 野田市 Noda-shi to 高松道場 Tak松 Dōjō in 奈良 Nara, 橿原 Kashihara, at least three times a month by express train, striving in the path of martial training where master and disciple’s hearts connect.

Thus, after fifteen years passed, in the 33rd year, he was entrusted with the lineage of 戸隠流忍法 Togakure-ryū Ninpō 34th generation, as well as 九鬼神伝八法秘剣 Kukishinden Happō Hiken 28th generation, 玉虎流骨指術忍法 Gyokko-ryū Koppojutsu Ninpō 28th generation, 虎倒流骨怯術 Kotō-ryū Kokkyaku-jutsu 18th generation, 義鑑流 Gikan-ryū 15th generation, 雲隠流忍法 Kumogakure-ryū Ninpō 14th generation, 神伝不動流打拳体術 Shinden Fudō-ryū Dakentaijutsu 26th generation, 高木

心流柔体術 Takagi Yōshin-ryū Jūtaijutsu 17th generation, and other eight school headships.

忍術 Ninjutsu, until 藤田西湖氏 Fujita Saiko-shi, was extremely orthodox in both technique and spirit, but with 初見氏 Hatsumi-shi, while inheriting ancient techniques, its spirit is modern, aspiring to the internationalization of 忍法 Ninpō, managing 武神館 Bujinkan, and striving to guide juniors. Many foreign martial artists learn from him, and presently, 初見道場 Hatsumi Dōjō branches exist in イスラエル Isuraeru, インド Indo, 英 Ei, 仏 Futsu, 米 Bei, スイス Suisu, デンマーク Denmāku.

Three Last Ninja Excerpts from the book Ninpō Chōjin no Sekai by Ōhira Yōsuke.

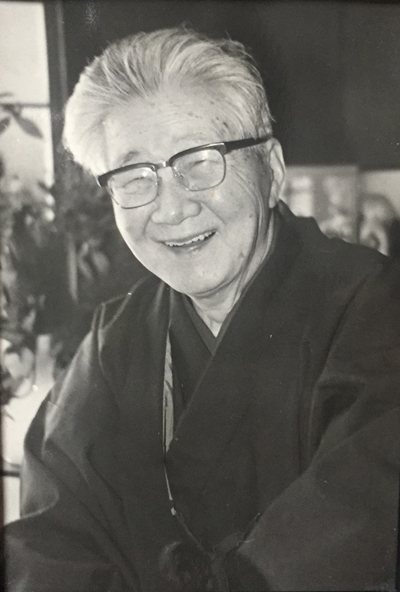

Endorsement by Hatsumi Yoshiaki

34th Sōke of Togakure-ryū Ninpō

28th Sōke of Kukishinden Happō Hiken

Upon hearing that Professor Ōhira was publishing an introductory book on ninjutsu, I was convinced that it would undoubtedly become an exceptional work on the subject. This confidence stems from the fact that Professor Ōhira has dedicated decades to researching ninjutsu—not merely by studying historical texts or research books on the subject, but by forming deep, familial bonds with living ninjas over many years. I am one of those ninjas.

Therefore, Professor Ōhira possesses knowledge of secret teachings (hiden) that a mere researcher could never glimpse.

I believe that ninjutsu is, in essence, a method of mastering the art of living with a spirit of harmony, peace, and joy (kasei waraku). To this end, ninjutsu practitioners have honed their wisdom to live happily by cultivating their body, mind, and spirit through endurance (nin).

In today’s chaotic era, isn’t the proper application of ninjutsu—despite its potentially dangerous nature—precisely what modern society needs? This book, which comprehensively elucidates all aspects of ninjutsu, not only explains the art but also serves as a personal guide for navigating life. This is why I, as a ninja, proudly endorse it to the world (kōko).

Yōsuke Ōhira (大平陽介)

Writer and literary critic. Real name: Ryōichi Yahata. Born in 1904 in Fukushima Prefecture. After dropping out of Chūō University’s Faculty of Law, he worked at Shinchōsha before serving as the inaugural editor-in-chief of NHK’s monthly magazine Broadcast and the Freedom Publishing Association’s Reading Outlook (a predecessor to the current Weekly Reading Person). He is currently a standing committee member of the Tokyo Writers’ Club and a councilor of the Japan Children’s Literature Association. His representative work is Full Moon Literature (Shunyō Bunko). Alongside his prolific writing career, he has a keen interest in exploring ancient martial arts (kobudō), and has authored works such as Sword Courage Record (Daidō Inshokan), which incorporates the secrets of martial arts. This book also reflects a portion of his extensive research accumulated over many years.

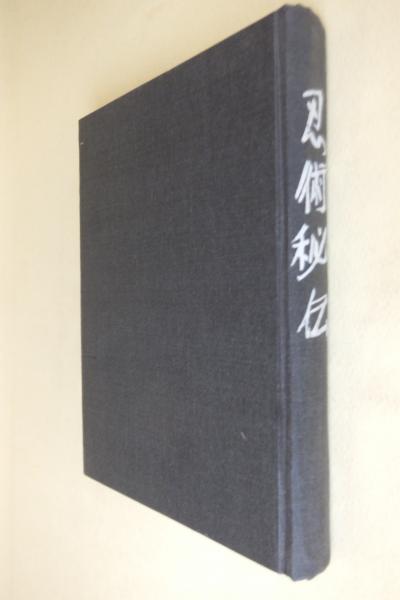

Published January 1, 1975

254 pages

ISBN-10 : 4026060314

ISBN-13 : 978-4026060316

The post History of Ninjutsu: Three Last Ninja appeared first on 武神館兜龍 Bujinkan Toryu.…